Onegin is a man bemused by his own worthlessness. He has been carefully prepared by his aristocratic 19th century upbringing to be unnecessary–an outside man, hanging on, looking into the lives of others. Even when he’s given the opportunity to play a role after he inherits his uncle’s estate, his response is to rent the land to his serfs. In another man, this would be seen as liberalism. In Evgeny Onegin, it is more like indifference.

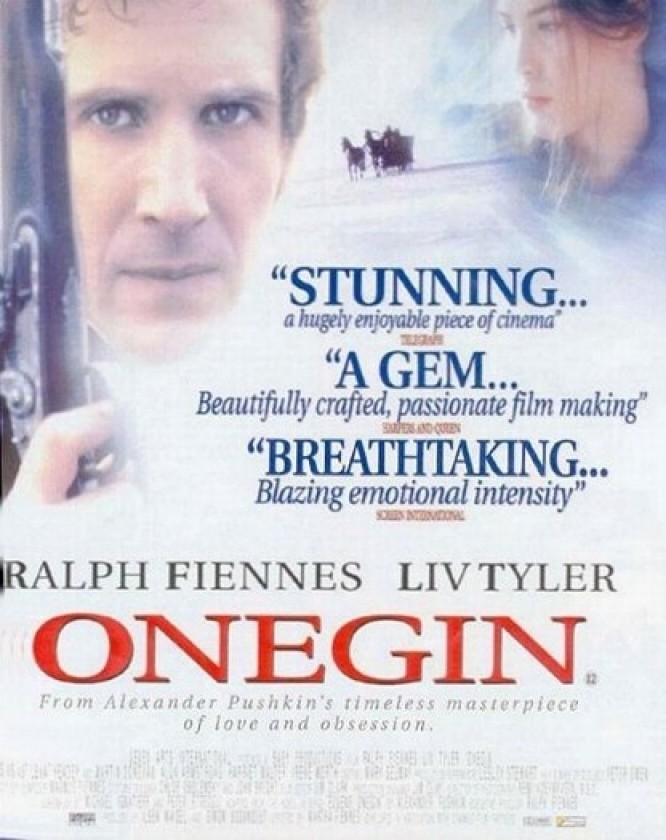

“Onegin” is a leisurely, elegant, detached retelling of Alexander Pushkin’s epic verse novel, with Ralph Fiennes as the hero. It is the kind of role once automatically assigned to Jeremy Irons. Both men look as if they have stayed up too late and not eaten their greens, but Irons in the grip of passion is able to seem lost and heedless, while Fiennes suggests it is heavy lifting, with few rewards. “I am not one who is made for love and marriage,” his Onegin says soulfully.

As the film opens, Onegin is returning to inherit his uncle’s estate outside St. Petersburg after having lost his own fortune at the gambling tables. He is welcomed by receptions, teas and balls, and embraced by his neighbor Lensky (Toby Stephens). Lensky has a young bride named Olga (Lena Headey), and she has an older sister named Tatyana (Liv Tyler), who is a lone spirit and visits Onegin’s estate to borrow books from his library.

Tyler has the assignment of suggesting passionate depths beneath a cool exterior and succeeds: She is grave and silent, with an ethereal quality that is belied by her bold use of eye contact. Onegin probably falls in love with her the first time he sees her, but is not, of course, made for love and shrugs off his real feelings in order to enter into a flirtation with Olga, who is safely married.

Tatyana’s waters run deep. She declares herself in a passionate love letter to Onegin (the moment she saw his face, she knew her heart was his, etc.), but such passion only alarms him. “Any stranger might have stumbled into your life and aroused your romantic imagination,” he tells her tactlessly. “I have no secret longing to be saved from myself.” “You curse yourself!” she cries, rejected. The heartless Onegin continues his dalliance with Olga. This leads to a duel with Lensky. His heart is broken when he kills his friend; that will teach him to call a 19th century Russian nobleman’s wife “easy.” Onegin flees to exile (or Paris, which are synonymous). Six years pass. He returns to St. Petersburg and sees Tatyana again, at a ball. But now the tables are turned, in ironic revelations and belated discoveries, and Onegin pays the price for his heartlessness.

There is a cool, mannered elegance to the picture that I like, but it’s dead at its center. There is no feeling that real feelings are at risk here. Tyler seems sincere enough, but Fiennes withholds too well. And the direction, by his sister Martha Fiennes, is deliberate and detached when it should perhaps plunge into the story. The visuals are wonderful, but the drama is muted.

There is a tendency to embalm classics, but never was a literature more tempestuous and heartfelt than in 19th century Russia. Characters joyously leap from the pages of Pushkin, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, wearing their hearts on their sleeves, torn between the French schoolmasters who taught them manners, and the land where they learned passion–inhaled it, absorbed it in the womb. I know Eugene Onegin is a masterpiece, but the story it tells is romantic melodrama and requires some of the same soap-opera zest as David Lean’s “Dr. Zhivago.” This film has the same problem as its hero: Its manners are so good, it doesn’t know what it really feels.

Note: In addition to its theatrical run, “Onegin” has been playing on cable. Since the photography, locations and landscapes are the best reason to see the film, the big screen is the way to go.