From The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to “Deliverance” to “Mud,” the river expedition can tell a story about America: about the hypocrisy of its racism, the brutality required for survival, or the human destruction of its landscape. When Ray McKinnon’s character Senior says in “Mud,” “Enjoy the river, son. Enjoy it while you live on it, ‘cause this way of life isn’t long for this world,” his wistfulness resonated because of how well Jeff Nichols’ film first built a sense of place, then made clear the impact of its loss. An odyssey of this kind requires narrative specificity—the before, and the after—to depict transformation, and that lack of particular detail plagues “Once Upon a River.” Laden with demoralizing tragedies, Haroula Rose’s film is only fleetingly affecting, preferring to put its characters through the wringer rather than provide them with much interiority or consistency. Without that depth, neither the external nor internal journeys of “Once Upon a River” captivate as much as they should.

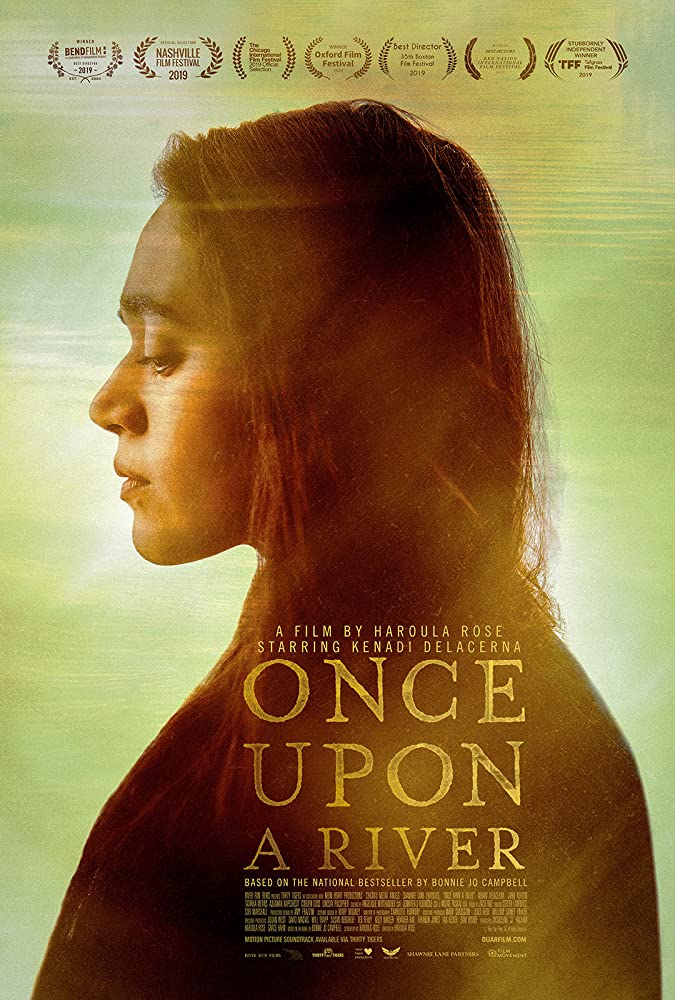

Rose’s feature-length directorial debut “Once Upon a River” is adapted from Bonnie Jo Campbell’s same-named novel, which was released to widespread positive reviews in 2011. Although the novel served as a prequel for Campbell’s “Q Road,” Rose has crafted the film version of “Once Upon a River” as a standalone piece—certain plot elements are tweaked, and entire subplots and characters removed. The film begins in rural Murrayville, Michigan, in 1977, where 15-year-old Margo Crane (Kenadi DelaCerna) lives on the shore of Stark River with her father, Bernard (Tatanka Means). Her mother, Luanne (Lindsay Pulsipher), left them a year before and hasn’t contacted her daughter since. In Luanne’s absence, Bernard teaches Margo how to shoot, fish, and live off the land, skills passed down to him by indigenous forebears. With Annie Oakley as her hero, Margo is an exemplary shot—catching the eye of her uncle, Cal (Coburn Goss), her father’s half-brother, whose white family basically runs the town.

While Bernard works more to make ends meet, Margo begins to spend more time with Cal, setting off a series of events that leaves one person dead, another injured, and Margo on the run. With her rifle in hand, Margo sets off on the river to try and find her mother. Along the way, she meets a number of men, and the film falls into a pattern of depicting Margo’s reliance on men without interrogating what that dependence means for the character. A friend of her father’s who had told Margo she was his “dream girl” and “I just can’t get enough of a girl who don’t talk” helps hide her from police. Later on, a graduate student, Will (Ajuawak Kapashesit), shares a meal with Margo, gives her a ride, and causes her to think more about her indigenous heritage by sharing details of his own ancestry: “I’m Cherokee from Oklahoma. People who came to this country and took over, they never intended for us to survive.” And in the longest chunk of “Once Upon a River,” Margo saves the life of Smoke (John Ashton), an older man with emphysema who is irritated by his daughters’ insistence that he move into an assisted-living facility.

“Why does anybody help anybody?,” Smoke replies when Margo wonders about his motivations, and the bald empathy of that statement suggests the movie “Once Upon a River” wants to be. There are scenes that argue for an openhearted treatment of those in need—as evidenced by how often we see Margo get into a dire situation that only an older man can help her out of—but that repetition only underscores how little is clear about what Margo herself wants or desires. She is an excellent shot, but we have no understanding of how she feels about killing or being the cause of death. She misses her mother, mentioning that Luanne smelled of “cocoa butter and white wine,” but offers no further observations about what her parents’ marriage was like, or how they ended up together. She was othered by her white relatives her whole life, but when Will asks about her tribe, she is utterly uncurious. The film begins with Margo’s narration, using her first-person voice to deliver exposition about her mother’s abandonment and her father’s tense relationship with his half-brother before dropping out after the first 15 or so minutes. But “Once Upon a River” would have benefited from committing to that cinematic device as a way to provide a peek into Margo’s inner thoughts; without them, she is mostly a cypher, and her most momentous decisions—in particular one she makes after reconnecting with Luanne—lack clarity.

That’s not necessarily a flaw of DelaCerna’s performance. DelaCerna’s posture and bearing make plain how self-possessed and tough Margo is, while her wide eyes and hesitant smile remind of her fragility and youth. But Margo herself is a muddled character, a victim of the narrative’s mistake that depicting trauma is more important than exploring its aftermath. DelaCerna does her best work opposite Pulsipher, but the women’s performances—one resentful but yearning; the other apologetic but wary—are let down by the simplistic dialogue of that reunion. Is the film trying to say that Margo doesn’t have the luxury of considering the effects of her actions, given the effort required for day-to-day survival? Perhaps, but that argument doesn’t hold much water when “Once Upon a River” also isn’t very interested in the scraping by Margo has to do to survive. She spends more time off the Stark River than on it, and while cinematographer Charlotte Hornsby’s framing of the waterway is often lovely (lots of golden-hour light, swaying trees, and glimpses of the wildlife living in the river), it seems at odds with the film’s insistence that Margo is venturing into danger.

Despite solid performances from DelaCerna and most of the rest of this ensemble cast, those unintentional contradictions are ultimately the defining quality of “Once Upon a River,” and they permeate the film with a sort of flatness. Is this a bleak story about the limited resources available to an indigenous young woman who is rejected by her small town, and about how we’re doomed to repeat our parents’ mistakes? Or is this an inspirational story about how home is wherever you find another person willing to lend a hand, and how you can build your own family? Perhaps the former could believably change into the latter with meaningful investment in the film’s characters, relationships, and sense of place, but the disparate “Once Upon a River” doesn’t accomplish that metamorphosis.

Available in virtual cinemas on Friday, October 2