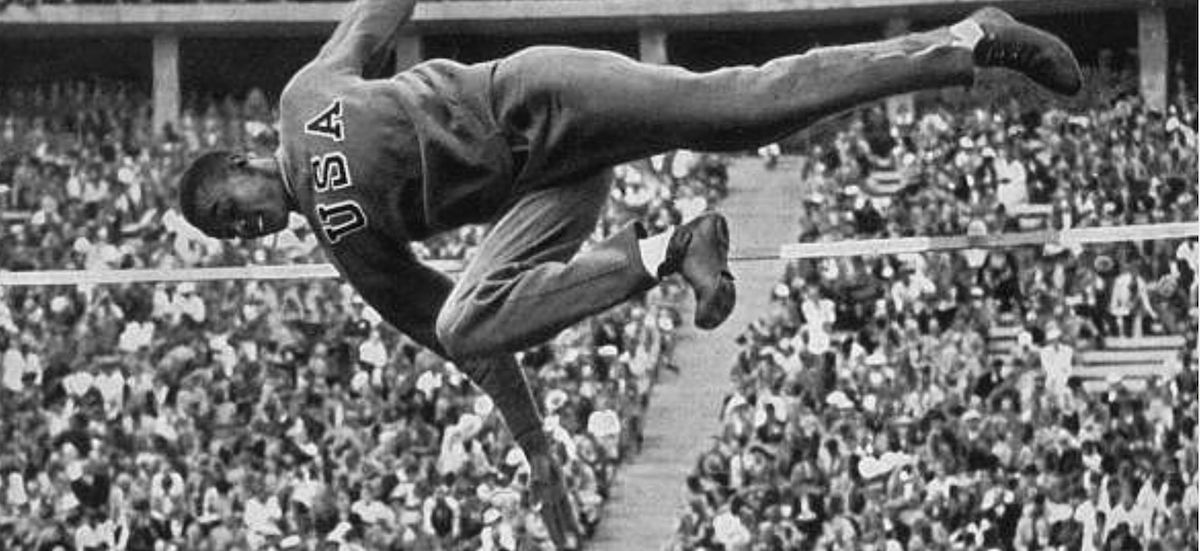

2016 marks the 80th anniversary of the 1936 Berlin Games. Adolf Hitler saw Germany-set games as a means of promoting the supposed superiority of his country’s White athletes. Hitler’s intentions were usurped by an African-American runner named Jesse Owens, whose undeniable prowess on the track earned him four Olympic gold medals. Of the Americans who participated in 1936, Owens’ story stood out not just for his victories, but for the ironies that accompanied it: Here was a man representing a country that thought him inferior to Whites competing in another country that held the same thought, yet treated him better because he was an Olympian.

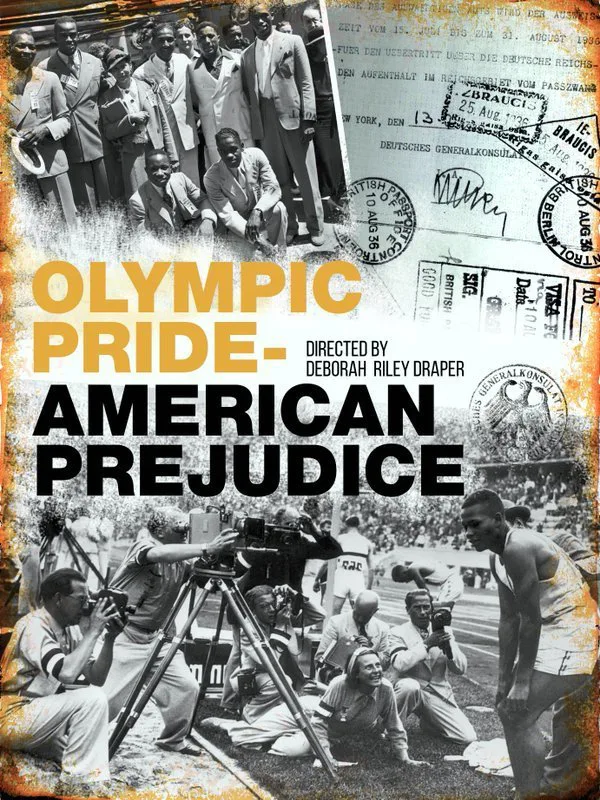

When the story of the 1936 Olympics is told, Owens stands out because, as the saying goes, the spoils are bestowed upon the victor. Yet, the standard Owens narrative I was fed during numerous “Black History Month” Februarys in my scholastic career never mentioned that Owens was not the only person of color to participate in Berlin. In fact, 17 other African-Americans (15 men and 2 women) accompanied Owens, some in his field of expertise, others in areas such as boxing and weightlifting. Deborah Riley Draper’s documentary, “Olympic Pride, American Prejudice,” tells the story of these unsung competitors, many of whom won medals of their own. It opens just in time for 2016’s own Olympic games, and is well worth the time and money.

“Olympic Pride, American Prejudice” is the second 2016 release to cover the Berlin games. Back in February, Stephen Hopkins’ bland, tone deaf Jesse Owens biopic, “Race” opened to lukewarm reviews and respectable box office. The difference between the two films is blatantly exposed by their titles and their respective genres: “Race” is a cutesy play on words denoting both Jesse Owens’ athletic prowess and his color. As a result, the audience is free to choose which meaning makes them more comfortable. By comparison, Draper’s title is fearlessly blunt. There’s only one way to interpret it, and as a documentary, “Olympic Pride, American Prejudice” is freed from the crowd-pleasing constraints imposed on the biopic genre.

Despite being well-acted and somewhat entertaining, two problems plagued Hopkins’ biopic. “Race” suffered from Hollywood’s inability to tell a Black story without involving a White character as audience stand-in, making propaganda documentarian Leni Riefenstahl into an almost bigger hero than Owens. The film also undercut the harsh realities of Owens’ story, muting the more sinister aspects of Avery Brundage’s role in the proceedings while also providing moments of manufactured hope that rang hollow and false. For example, both Draper and Hopkins inform the viewer that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt neither met with Owens, nor did he publicly congratulate him. But only Draper’s film tells you the offensive reason why. Additionally, both films mention that Owens was forced to enter the event honoring him using the back entrance of the Waldorf-Astoria, but “Race” tacks on an unconvincing moment of post-racial harmony to soften the blow.

“Olympic Pride, American Prejudice” tackles its subject in a straightforward manner freed from dramatic license and the fear of box office failure. Though narrated by actor Blair Underwood (who also produced), the most prominent voices heard are those of the athletes who participated in the games. Many of them lived into the last few decades of the 20th century, and some had other achievements that were just as fascinating as their Olympic competitions. Though Draper expertly provides archival footage and pictures of her subjects, I wanted to close my eyes whenever one of the Olympians spoke, so that their words could wash over me in complete darkness. Black history is so often an oral tradition, passed down from generation to generation through the voices of those who lived the events or knew of them. “Olympic Pride, American Prejudice” honors that with judicious audio choices gleaned from the pure luck of having these narratives available, though it must not have been easy obtaining them.

Testimonies of the athlete’s children also provide much-needed information. Sprinkled throughout these talking head moments are undercurrents of anger and sadness about how history has all but forgotten everyone but Owens, either due to the racism of the time or the careless notion that the success story of one person of color was more than enough for the 1930’s era public to handle. For example, the Olympic fate of Louise Stokes, who with Tidye Pickett became the first Black women selected for the U.S. team, is particularly infuriating and upsetting, but those emotions are coupled with the uplift from her resulting perseverance.

Out of respect and admiration, I am compelled to list each of the 18 athletes’ names to close out this review. “Olympic Pride, American Prejudice” tells not just how they did in the Olympics but also how they fared in life after the games were done. Their stories are well worth hearing. This list may feel as long as the closing credits reel of a Marvel movie, but that’s appropriate; these people were superheroes:

Jesse Owens and his lifelong friend, Dave Albritton; Tidye Pickett, John Brooks, boxers James Clark, Willis Johnson, Jack Wilson, Art Oliver and Howell King; Cornelius Johnson, Dr. James LuValle, U.S. Representative Ralph Metcalfe, Fritz Pollard, Jr., Jackie Robinson’s older brother, Mack Robinson; Louise Stokes, weightlifter John Terry, Archie Williams and John Woodruff.