Fiction writers have long played with the idea that violence begets violence, and not always in a linear way. Action movies often deal with the literal repercussions of violence, but there have been some great pieces of fiction built around the idea that once you open the door to a violent world, you can’t close it again (several Coen scripts play with this theme). The best parts of Avi Belkin’s six-part Sundance docu-series “No One Saw a Thing” examine the theme that violence, especially of the vigilante kind, leaves a scar. It doesn’t end when the violent act ends. It changes the tenor of the atmosphere. It changes the way people look at their neighbors. It alters the landscape of what could possibly happen in a small town in the heartland. Belkin’s docu-series could have accomplished much of what it set out to do in roughly half the running time, but it’s never boring and often fascinating, especially when it confronts how a society built on a foundation of violence is bound to suffer again.

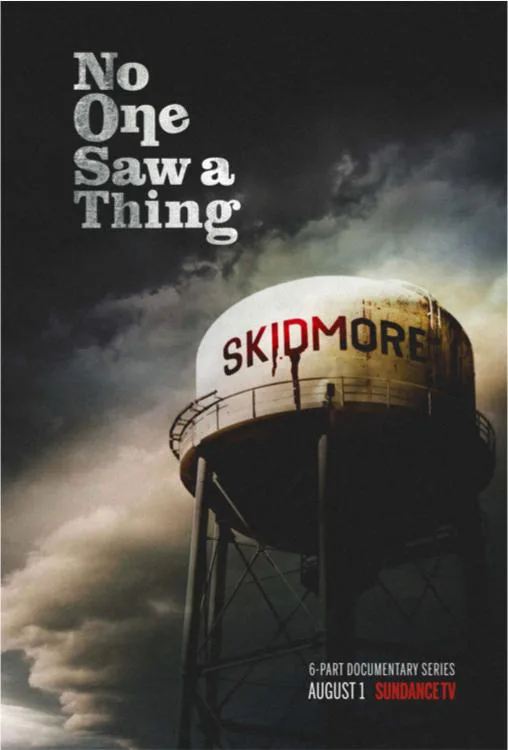

On July 10, 1981, Ken Rex McElroy was shot dozens of times in his truck, sitting in the middle of the street in Skidmore, Missouri. It was in broad daylight. His young wife was with him, so an eyewitness was left alive. And almost the whole town watched as it happened—three to five people pulled out weapons and plugged McElroy’s body so full of bullets that his body came apart. McElroy was the town bully. He shot at a grocery store owner and was accused of raping a 13-year-old, who he then married to stop from testifying against him. He also may have burned down a house. And the authorities seemed unable to stop him. He terrorized a small town—although Belkin is careful to present the counter-argument that all of this was overblown after the fact, especially from McElroy’s children. Despite nationwide news coverage and a federal investigation after the murder, no one was arrested. No one saw a thing.

Why and how an entire American smalltown conspired to kill a man and then keep it a secret for generations is the focus of the first few episodes of “No One Saw a Thing.” A lot of the major players are already deceased—most of the “town elders” were, well, elder then and this was almost forty years ago—so Belkin weaves together a great deal of archival footage with modern-day interviews. A lot of the archival stuff comes from a Morley Safer segment from “60 Minutes” in 1982, which leads one to wonder if Belkin didn’t come across this story doing research for his “Mike Wallace Is Here,” the director’s recently-released documentary about the legendary newsman (Wallace would have liked this film, by the way). The modern-day interviews sometimes reminded me of Errol Morris’ wonderful examinations of small-town American life – both insightful and a bit loving of the eccentricities on display.

Belkin’s project gains depth when he confronts the idea that the McElroy murder destroyed Skidmore. Over the next few decades, Skidmore saw more than its fair share of crime per capita—subsequent episodes examine a horrible spousal abuse case, the saga of a missing young man, and a brutal murder of a pregnant woman—and the place has basically turned into one of those heartland ghost towns. Would Skidmore be a bustling metropolis if its residents hadn’t become vigilante murderers? Doubtful. And yet there’s something to the idea that a secret that big—knowledge that the entire town is full of either murderers or their accomplices—destroys a place and weighs on its people. Safer seemed to understand way back in 1982 in his segment that what the residents of Skidmore had done could have way more lasting damage than anything McElroy could do. Belkin’s series proves him right.