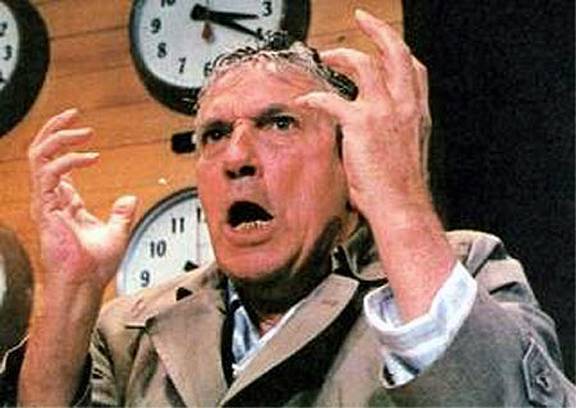

There’s a moment near the beginning of “Network” that has us thinking this will be the definitive indictment of national television we’ve been promised. A veteran anchorman has been fired because he’s over the hill and drinking too much and, even worse, because his ratings have gone down. He announces his firing on his program, observes that broadcasting has been his whole life, and adds that he plans to kill himself on the air in two weeks.

We cut to the control room, where the directors and technicians are obsessed with getting into the network feed on time. There are commercials that have to be fit in, the anchorman has to finish at the right moment, the buttons have to be pushed, and the station break has to be timed correctly. Everything goes fine. “Uh,” says somebody, “did you hear what Howard just said?” Apparently nobody else had.

They were all consumed with form, with being sure the commercials were played in the right order and that the segment was the correct length. What was happening — that a man has lost his career and was losing his mind — passed right by. It wasn’t their job to listen to Howard, just as it wasn’t his job to run the control board. And what “Network” seems to be telling us is that television itself is like that: An economic process in the blind pursuit of ratings and technical precision, in which excellence is as accidental as banality.

If the whole movie had stayed with this theme, we might have had a very bitter little classic here. As it is, we have a supremely well-acted, intelligent film that tries for too much, that attacks not only television but also most of the other ills of the 1970s. We are asked to laugh at, be moved by, or get angry about such a long list of subjects: Sexism and ageism and revolutionary ripoffs and upper-middle-class anomie and capitalist exploitation and Neilsen ratings and psychics and that perennial standby, the failure to communicate. Paddy Chayefsky’s script isn’t a bad one, but he finally loses control of it. There’s just too much he wanted to say. By the movie’s end, the anchorman is obviously totally insane and is being exploited by blindly ambitious programmers on the one hand and corrupt businessmen on the other, and the scale of evil is so vast we’ve lost track of the human values.

And yet, still, what a rich and interesting movie this is. Lumet’s direction is so taut, that maybe we don’t realize that it leaves some unfinished business. It attempts to deal with a brief, cheerless love affair between Holden and Dunaway, but doesn’t really allow us to understand it. It attempts to suggest that multinational corporations are the only true contemporary government, but does so in a scene that slips too broadly into satire, so that we’re not sure Chayefsky means it. It deals with Holden’s relationship with his wife of twenty-five years, but inconclusively.

But then there are scenes in the movie that are absolutely chilling. We watch Peter Finch cracking up on the air, and we remind ourselves that this isn’t satire, it was a style as long ago as Jack Paar. We can believe that audiences would tune in to a news program that’s half happy talk and half freak show, because audiences are tuning in to programs like that. We can believe in the movie’s “Ecumenical Liberation Army” because nothing along those lines will amaze us after Patty Hearst. And we can believe that the Faye Dunaway character could be totally cut off from her emotional and sexual roots, could be fanatically obsessed with her job, because jobs as competitive as hers almost require that. Twenty-five years ago, this movie would have seemed like a fantasy; now it’s barely ahead of the facts.

So the movie’s flawed. So it leaves us with loose ends and questions. That finally doesn’t bother me, because what it does accomplish is done so well, is seen so sharply, is presented so unforgivingly, that “Network” will outlive a lot of tidier movies. And it won several Academy Awards, including those for Peter Finch, awarded posthumously as best actor; Chayevsky for his screenplay; Beatrice Straight, as best supporting actress; and Faye Dunaway, as best actress. Watch her closely as they’re deciding what will finally have to be done about their controversial anchorman. The scene would be hard to believe — if she weren’t in it.