The thing about movie love scenes is that they are acting and they are not acting, both at the same time. Two actors play “characters” who kiss or caress or thrash about. They are only “acting.” When the director shouts, “cut!” they disengage and wander off to their trailers to finish the crossword puzzle. That at least is the idea they give in interviews.

But consider. Most movie actors are attractive. They come wrapped in a mystique. Everyone is curious about them, including their co-stars. When the director says, “action!” and they find themselves in bed, there is the presence and warmth of the other person, the press of bosom or thigh, the pressure of a hand, the softness of lips. Does something happen that is not precisely covered by the definition of acting? If it does not, then the actors are not humans and should not be playing them. If we in the audience sometimes feel a stirring of more than artistic interest in some of the people we see on the screen, should actors, whose experience is so much more immediate, be any different? The fact that they are not different provides the subtext for half of the articles in the supermarket tabloids.

Consider all that, and I will tell you a story. I interviewed Robert Mitchum many times. He co-starred with Marilyn Monroe. I never asked him anything as banal as “What was it like to kiss Marilyn Monroe?” but of course there is no woman in the history of the movies who would inspire a greater desire to ask that question. Once, though, as I was Q&A-ing Mitchum at the Virginia Film Festival, somebody in the audience asked him about Marilyn.

“I loved her,” he said. “I had known her since she was about 15 or 16 years old. My partner on the line at the Lockheed plant in Long Beach was her first husband. That’s when I first met her. And I knew her all the way through. And she was a lovely girl–very, very shy. She had what is now recognized as agoraphobia. She was terrified of going out among people. At that time, they just thought she was being difficult. But she had that psychological, psychic fear of appearing among people. That’s why when she appeared in public, she always burlesqued herself. She appeared as you would hope that she would appear. She was a very sweet, loving and loyal–unfortunately, loyal–girl. Loyal to people who used her, and a lot who misused her.” So there you have it. Not what it was like to kiss her, but what it was like to know her. In one paragraph, probably as much truth as can be said about Monroe.

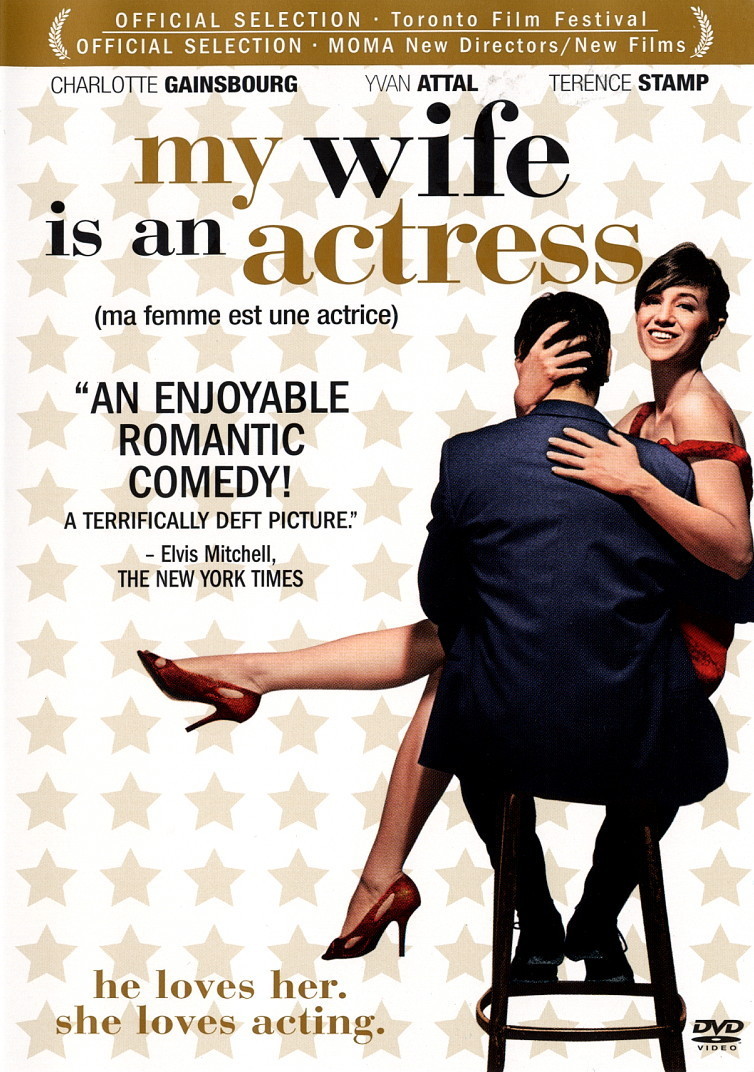

An answer like that is beyond the new movie “My Wife Is an Actress.” This is a French seriocomedy written, directed by and starring Yvan Attal, who plays a Paris sportswriter whose wife is a famous actress. She is played by Charlotte Gainsbourg, who in real life is Attal’s wife. No doubt if he were to write a serious novel about his marriage, Attal would have some truths to share, but his film feels like an arm’s-length job, a comedy that deliberately avoids deep waters.

Yvan is a jealous man. He is driven to it by an unrelenting barrage of questions from members of the public, some of whom assume as a matter of course that Charlotte really does sleep with her co-stars. He smashes one guy in the nose, but that doesn’t help, and when Charlotte goes to London to work with a big star (Terence Stamp), Yvan all but pushes her into his arms, to prove his point.

Stamp, who is very good in a thankless role, plays a man so wearied by life and wear and tear that he sleeps with women more or less as a convenience. He seduces to be obliging. There is a funny moment when he propositions a woman and soberly accepts her refusal as one more interesting development, nodding thoughtfully to himself.

If the movie were all comedy, it might work better. But it has an ambition to say something about its subjects, but not a willingness. It circles the possibility of mental and spiritual infidelity like a cat wondering if a mouse might still be alive. Watching it, I felt it would be fascinating to see a movie that was really, truthfully, fearlessly about this subject.