Over the past half-century, Neil Young has followed his muse into any number of different musical genres and has played with enough different groups to fill an entire wing at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. However, amidst his relentless, defining desire for change, the one constant has been Crazy Horse, the rock band he began performing with back in 1969. They collaborated on albums ranging from stone classics like Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (1969), Rust Never Sleeps (1979) and Ragged Glory (1990), to underrated gems like Re-ac-tor (1981) and the sprawling ecologically-themed concept album Greendale (2003). Granted, the band’s loud and driving sound is not to everyone’s tastes—writing about “Year of the Horse,” Jim Jarmusch’s 1997 documentary on Young and the group, a noted critic said that their sound “gets mired in endless loops of instrumental repetition that seems positioned somewhere between mantras and autism. The music is shapeless, graceless and and built from rhythm, not melody”—but Young has clearly gotten something out of this particular artistic collaboration that has inspired some of his greatest work. It is this spirit that he, under his longtime nom de film Bernard Shakey, celebrates in the appropriately ragged documentary “Mountaintop.”

The film is neither a straightforward performance movie like the classic concert doc “Rust Never Sleeps” nor is it a historical overview along the lines of the aforementioned “Year of the Horse.” Instead, it offers a fly-on-the-wall perspective of Young and the group—guitarist Nils Lofgren, bassist Billy Talbot and drummer Ralph Molina—as they hole up in a studio in the Rocky Mountains to record their latest album, Colorado, their first since 2012’s Psychedelic Pill. That’s pretty much it. There are no interviews in which Young or anyone else discuss the numerous professional and personal changes that have occurred since that last album, ranging from the passing of Young’s manager Elliott Roberts (to whom the film is dedicated) to the departure of longtime rhythm guitarist Frank “Poncho” Sampedro. In fact, there are not even any subtitles to formally identify any of the people that we see throughout the film.

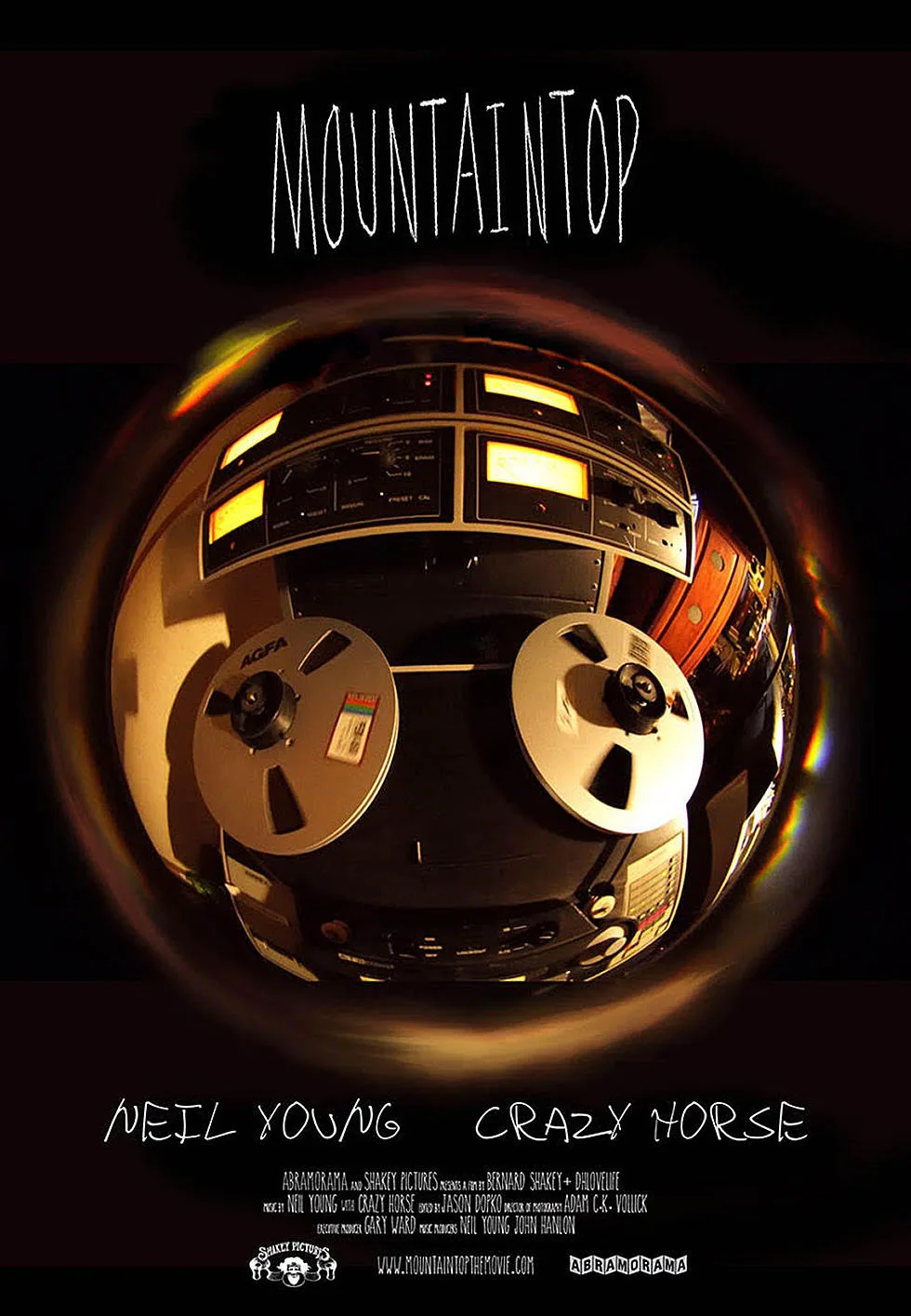

“Mountaintop” is similarly restricted from a visual perspective. Despite the scenic locale of the recording studio, there are only a couple of moments when the band and the film step outside for a bit of fresh air. Most of the footage has been shot from small digital cameras that have been placed throughout the studio and is put together in a deliberately repetitive shot pattern that at times utilizes angles normally associated with security cameras. For some people, this particular approach may strike them as somewhere between irritating and downright perverse. But it proves to be an intriguing stylistic gambit from Young and cinematographer Adam Vollick, who create a visual equivalent to the Crazy Horse sound—something that might seem to be plodding and monotonous on the surface but proves to be far more inspired than that.

The film’s real focus is to allow viewers to not only glimpse at the group’s creative process, but to also show once and for all that Crazy Horse is more than just a group of guys who can play really loud. As we watch the songs take shape, we get a real sense not just of the sheer amount of craft that goes into their recordings, but the almost psychic bond that they have developed between themselves when performing, allowing them to hit incredible grooves together.

Of course, things are not always perfect, and some of the film’s most amusing parts come when things threaten to develop into “Spinal Tap”-style chaos. At one point, there’s some confusion as to what part of a song is the chorus and what part is the verse. Later, there is an extended miscommunication with producer John Hanlon, listening in from the recording booth, that threatens to turn into a rocker version of “Who’s On First?” Throughout the film, there are constant complaints about the monitors and the troublesome wiring in the studio that so drive Hanlon to distraction that he orders one of the tech people to remove the camera from the booth so that Young cannot see his reaction. (Hilariously, the camera is still going as the guy disconnects and walks away with it.)

For fans of Neil Young and Crazy Horse, “Mountaintop” is pretty much a must-see—it gives them a chance to see their heroes at work in a raw and unfiltered manner, and the fact that the Colorado album is Young’s strongest collection of new songs since Psychedelic Pill is certainly a sweetener to the deal. Those who cannot stand their sound, on the other hand, are not likely to be won over. As a longtime fan of Young in all of his music phases (with the possible exception of that album of songs about the Lincoln Continental he retooled to run on alternate energy), I suppose I have a bias towards him that I cannot deny.