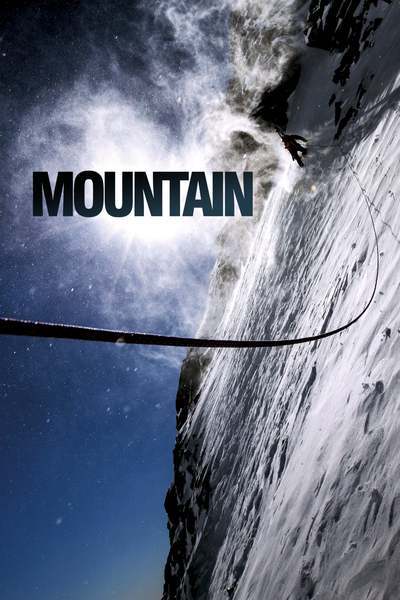

The mountains are alive with the sound of chamber music, as well as Willem Dafoe’s distinctive vocal intonations as a narrator, in the essay-style documentary “Mountain.” But neither can compete with the spellbinding sight of soaring slabs of craggy stone stabbing into the rippling cloud-draped heavens as filmed by German-born cinematographer Renan Ozturk, a specialist at capturing nature at a considerable height, and Australian director Jennifer Peedom.

This vertiginous valentine to high-altitude sport attempts to portray, in the most poetic of terms, why mankind feels the need to defy gravity by painstakingly clawing its way into the upper reaches of the atmosphere while risking life and limb. There is a segment where we see a man lose his footing and bang against a massive vertical expanse of rock like a dangling doll. Another unlucky climber shows off his bloodied fingers, each one possibly broken. But that harsh reality is intercut by the wonder and joy of actually reaching the summit, or as Dafoe calls it, “life on a knife’s edge.”

There is a good reason behind the singular nature of the title. The words spoken by Dafoe are drawn from Robert Macfarlane’s philosophical tome “Mountains of the Mind.” Instead of a stream of historical facts, interviews and data, we are awash in awe-inducing images that allow us to contemplate “the siren song of the summit.” Drones, Go-Pros and helicopters were employed to capture 2,000 hours of footage in 22 countries, including Antarctica, Australia, Canada, Italy, Tibet, New Zealand, South Africa and the USA.

But save for the King Kong of all climbs, Nepal’s Everest, the locales of each soaring spire are never revealed. Instead, Peedom, who covered similar ground in 2015 with the more traditional doc “Sherpa,” aims for an immersive visual experience that is meant to engage emotions more than the brain. Whether the mountains showed are encased in massive mounds of ice, coated in rolling waves of red clay or seared by a slithering flow of red-hot lava, it’s the sensation they trigger in us that counts most.

Abetting that goal is an inspirational string-heavy score by Richard Tognetti. As beautifully mood-inducing as the accompaniment is, it is sometimes too eager to provide aural clues on how to react to when a skier falls out of a helicopter and lands on a never-ending vast expanse of snow. Or when we witness the crass commercialization of the sport as swarms of eager cliff hangers descend upon Everest on a regular basis. Some perspective on the history of conquering Mother Nature’s monoliths is briefly provided by vintage clips of mountaineers using various new-fangled transport to assist them ever skyward. But for the most part, this is a sightseer’s delight.

However, the images that most ignited my imagination were those that required the camera to pull far, far away and turn the humans on the slopes and slabs into ant-like figures, often parading behind one another or swiveling downhill side by side in formation as if part of a Busby Berkeley routine. It’s just one of many panoramic perspectives that most of us would never get a chance to witness otherwise. Reducing man to insect-size while surrounded by monstrous formations is a reminder how insignificant we are when it comes to our world. It is not so much that we conquer these mountains, but that they allow us—most of the time—to conquer them.

The one drawback to this take on the subject is that the in-the-moment experience of seeing “Mountain” begins to vaporize from memory almost as the end credits start to roll. That isn’t a necessarily a bad thing. But as someone who was briefly fixated on the 1998 70mm IMAX movie “Everest,” which captured of the infamous deadly blizzard in 1996 that claimed eight lives and was later recounted in the bestseller “Into Thin Air”—and, yes, I even watched the so-so TV movie of the tragic aftermath—I get the daredevil-ish draw inherent in pushing yourself to such physically demanding limits. But I would much rather experience such altitudinal fever second hand. The best thing about “Mountain”? It does all the hard work for you.