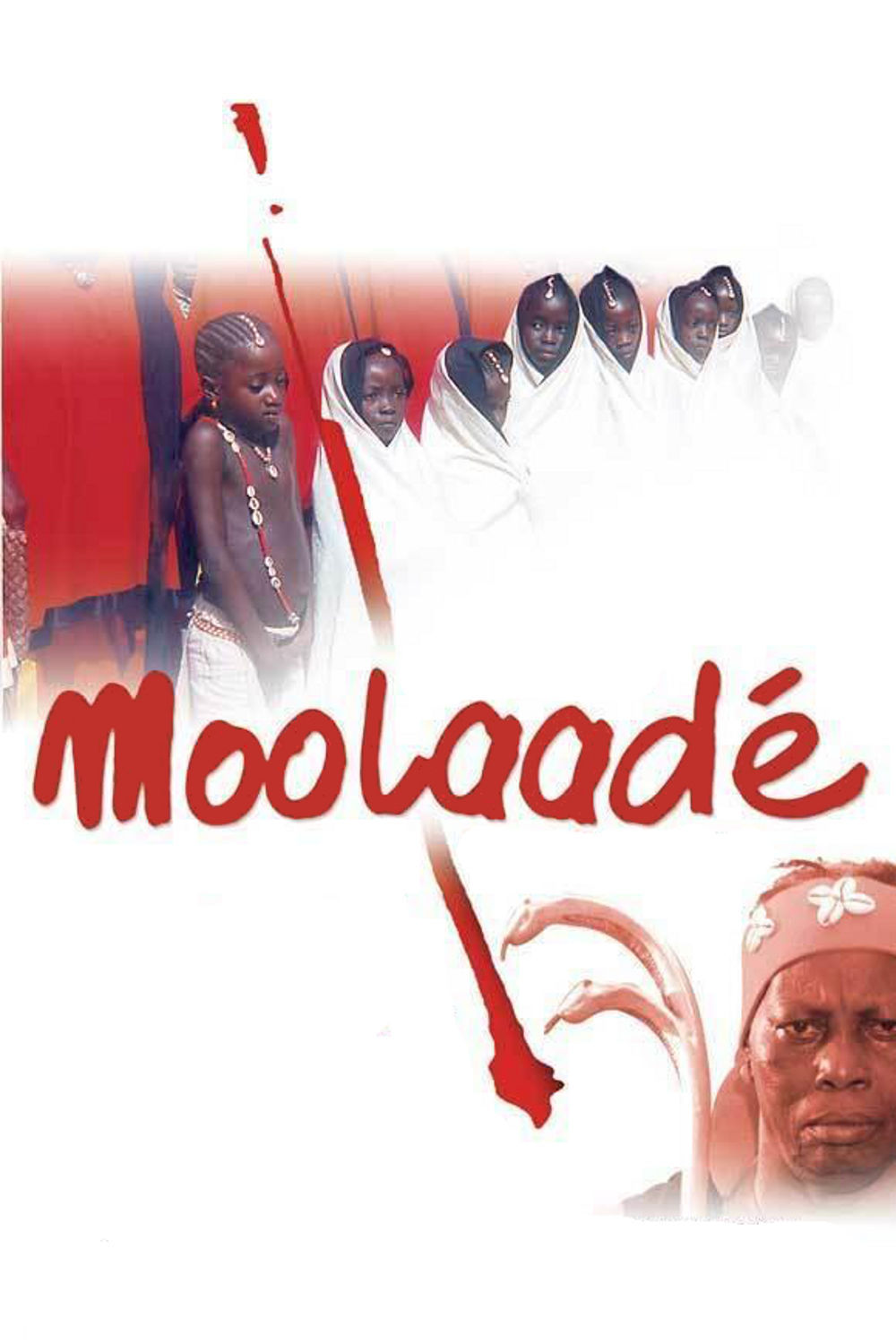

Sometimes I seek the right words, and I despair. What can I write that will inspire you to see “Moolaade?” This was for me the best film at Cannes 2004, a story vibrating with urgency and life. It makes a powerful statement and at the same time contains humor, charm and astonishing visual beauty.

But even my words of praise may be the wrong ones, sending the message that this is an important film, and therefore hard work. Moviegoers who will cheerfully line up for trash are cautious, even wary, about attending a film they fear might be great. And if I told you the subject of the film is female circumcision — would I lose you? And if I placed the story in an African village, have you already decided to see “National Treasure” instead?

All I can tell you is, “Moolaade” is a film that will stay in my memory and inform my ideas long after other films have vaporized. It takes place in a village in Senegal, where ancient customs exist side by side with battery-powered radios, cars and trucks, and a young man returning from Paris. Traditional family compounds surround a mosque; they are made in ancient patterns from sun-baked mud and have the architectural beauty of everything that is made on the spot by the people who will use it, using the materials at hand. The colors of this world are the colors of sand, earth, sky and trees, setting off the joyous colors of the costumes.

It is the time for several of the young women in the village to be “purified.” This involves removing parts of their genitals so they will have no feeling during sex. The practice is common throughout Africa to this day, especially in Muslim areas, although Islam in fact condemns it. Many girls die after the operation, and during the course of this movie, two will throw themselves down a well. But men, who in their wisdom assume control over women’s bodies, insist on purification. And because men will marry no woman who has not been cut, the older women insist on it, too; they have daughters who must find husbands.

Colle (Fatoumata Coulibaly), the second of four wives of a powerful man, has refused to let her daughter be cut. Now six girls flee from a purification ritual, and four of them seek refuge with her. Colle agrees to help them, and invokes “moolaade,” a word meaning “protection.” She ties a strand of bright yarn across the entrance to her compound, and it is understood by everyone that as long as the girls stay inside the compound, they are safe, and no one can step inside to capture them.

These details are established not in the mood of a dreary ethnographic docudrama, but with great energy and life. The writer and director is Ousmane Sembene, sometimes called the father of African cinema, who at 81 can look back on a life during which he has made nine other films, founded a newspaper, written at least five novels, and become, in the opinion of his distributor, the art film pioneer Dan Talbot, the greatest living director. Sembene’s stories are not the tales of isolated characters; they always exist within a society which observes and comments, and sometimes gets involved. Indeed, his first film, “Black Girl” (1966), is the tragedy of a young African woman who is taken away from this familiarity and made to feel a stranger in Antibes.

The village in “Moolaade” has an interesting division of powers. All authority allegedly resides with the council of men, but all decisions seem to be made by the women, who in their own way make up their minds and achieve what they desire. Men insist on purification, but it is really women who enforce it — not just the fearsome women who actually conduct the ceremony, but ordinary women who have undergone it and see no reason their daughters should be spared.

Colle has seen many girls sicken and die, and does not want to risk her daughter. She knows, as indeed most of those in the village know, that purification is dangerous and unnecessary and has been condemned even by their own government. But if a man will not marry an unpurified daughter, what is a mother to do? This is particularly relevant for Colle, whose own daughter, Amsatou (Salimata Traore), is engaged to be married to a young man who will someday rule their tribe, and who is a successful businessman in Paris. Yes, he is modern, is educated, is cosmopolitan, but in returning to his village for a bride of course he desires one who has been cut.

Local characters stand out in high relief. There is Mercenaire (Dominique T. Zeida), a peddler whose van arrives at the village from time to time with pots, pans, potions and dry goods, and who brings news from the wider world. There’s spontaneous fun in the way the women bargain and flirt with him.

And there is the doyenne des exciseuses (Mah Compaore), whose livelihood depends on her purification rituals, and who rules a fierce band of assistants who could play the witches in “Macbeth.”

Much of the humor in the film comes from the ineffectual debates of the council of men, who deplore Colle’s action but have been checkmated by the invocation of moolaade. One ancient tradition is thwarted by another. Colle’s husband, who has been away, returns to the village and insists that she hand over the girls, but she flatly refuses, and in a scene of drama and rich humor, the husband’s first wife backs up the second wife’s position and supports her.

All of this nonsense is caused by too much outside influence, the men decide. All of the radios in the village are collected and thrown onto a big pile near the mosque — where, in an image that lingers through the last scenes of the film, some of them continue to play, so that the heap seems filled with disembodied voices. Colle stands strong. Then the young man from Paris arrives, and the whole village holds its breath, poised between the past and the future.

Sembene’s “Guelwaar” (1994), a rich human comedy about a Catholic corpse mistakenly buried in a Muslim cemetery, is reviewed, along with his “Black Girl” and “Xala,” at rogerebert.com