In an opening scene of “Monsieur Lazhar,” it’s Simon’s day to pick up cartons of milk and deliver them to his Montreal fourth-grade classroom before the school day begins. Looking in through the door, he realizes that his teacher has hung herself from a ceiling pipe. Only one other student sees this before the teachers usher all the students back into the playground.

This incident, reported in a Quebec newspaper, is the inspiration for Bachir Lazhar (Fellag) to present himself at the school principal’s office and volunteer to teach the class. He is a legal immigrant from Algeria, he explains, where he taught primary school for 19 years. The principal is Mme. Vaillancourt (Danielle Proulx), who like most school administrators these days, is rigid in conforming to the rules. Hiring Monsieur Lazhar is a bit of an excursion for her, but he is a well-spoken, presentable man and makes a good impression.

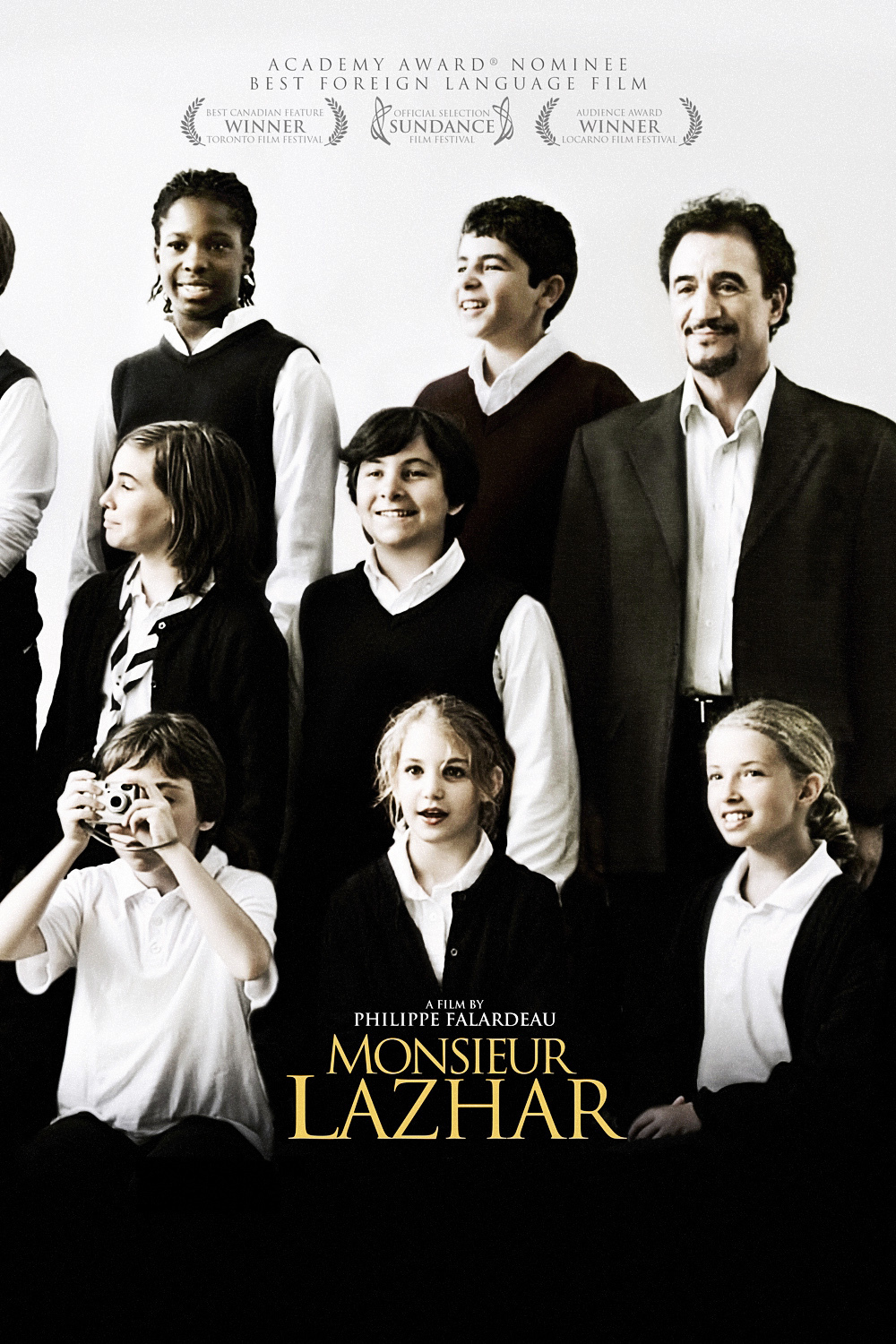

“Monsieur Lazhar,” which begins in the dead of winter, follows his work in the classroom all the way through until summer. During that time, he — and we — get to know the students, who are generally cheerful and well-behaved, and get on well with their new teacher. They are assumed to be traumatized by their teacher’s suicide, and a psychologist is assigned to spend closed-door sessions with the class. We, and Monsieur Lazhar, are closed out of these sessions, but Lazhar on his own tells the students some gentle truths and assures them it wasn’t their fault.

For this and other transgressions, he is criticized by the principal; to follow the rules, a teacher seems hardly allowed to be human. A student throws a paper ball at a classmate, and Lazhar, standing right there, taps him sharply on the head. This, too, is wrong; teachers are forbidden to touch students in any way. God forbid they would hug one, or pat one on the shoulder. I now realize that when Sister Ambrosina in the first grade at St. Mary’s in Champaign snapped us with a strict fingernail it was brutality, although I always knew why I had it coming.

Lazhar has some challenges. French is spoken differently in Algeria and Quebec — and in France too, perhaps. He dictates some Balzac for the students to write down and is informed by them it is “prehistoric.” He finds a sympathetic fellow teacher to confide in, and perhaps she also rather likes him.

There is a great deal more to be known about Monsieur Lazhar’s personal life, which I won’t reveal. It adds an additional dimension to the trauma of the students. Simon in particular blames himself for the suicide; the dead teacher must have known he would bring the milk to class that day, he reasons, and must have known he would find her hanging body. Why else would a teacher choose to hang herself in her schoolroom?

It’s a question without an answer. One of the qualities of “Monsieur Lazhar,” which was one of this year’s Academy Award nominees in the foreign-language film category, is that it has no simple questions and simple answers. Its purpose is to present us with a situation, explore the people involved and show us a man who is dealing with his own deep hurts.