“Moll Flanders” tells the story of a child born in prison to a mother who is hanged immediately afterward. Sent to a convent, she stabs a priest with a knitting needle when he tries to fondle her, and is cast into the streets of 18th century London, where the “warm and pretty glow” of a red lantern lures her into a bordello.

Her adventures as a prostitute lead to the great love affair of her life, with an artist who lives in poverty even though he comes from a rich family. He dies, she has a daughter, they are separated, and that’s more or less where we came in; the movie begins with a mysterious man fetching Moll’s daughter from an orphanage to take her on a journey, and tell her the story of Moll’s life.

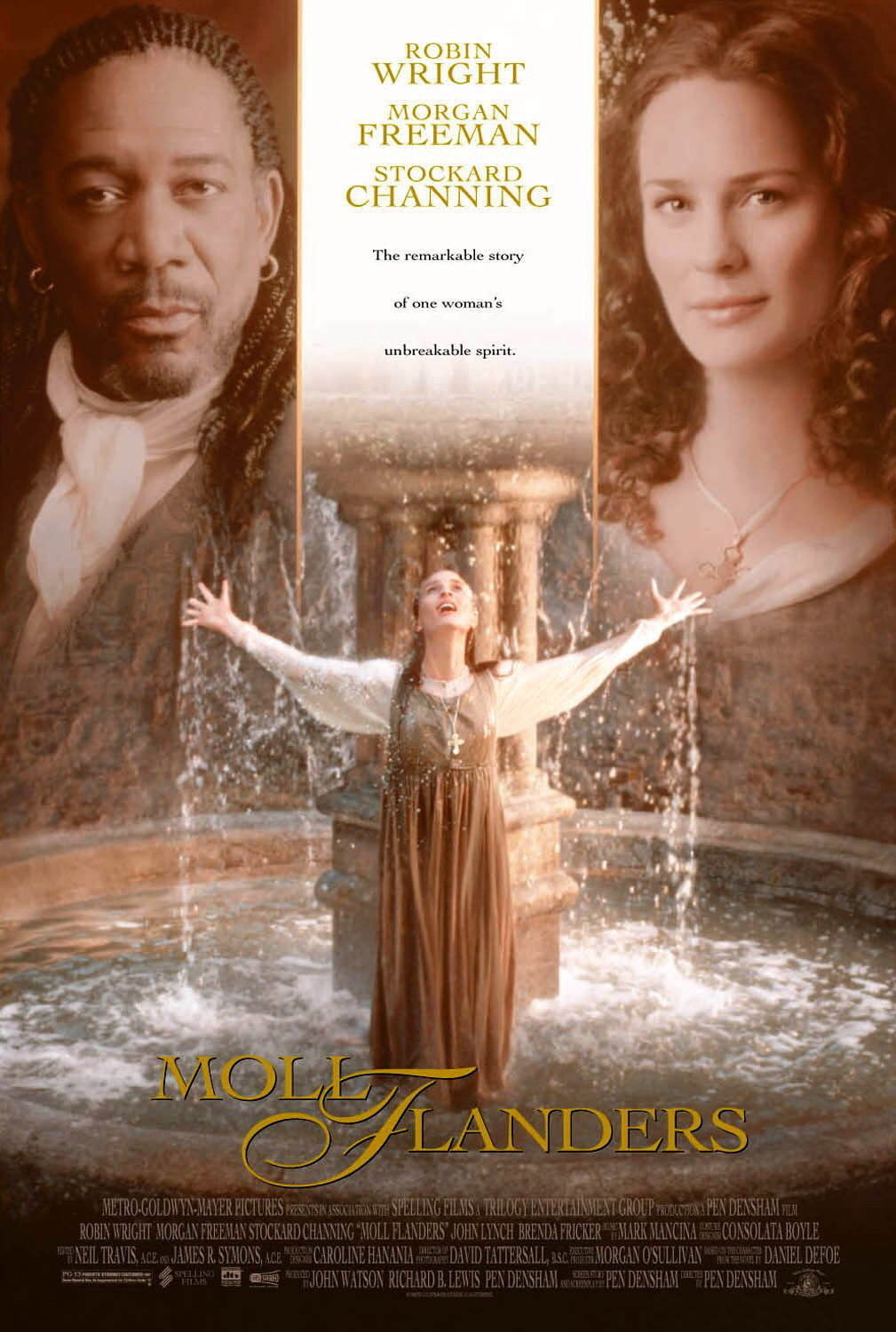

This sounds like the plot of a historical bodice-ripper, but “Moll Flanders” is more pensive and thoughtful than sensational–the story of a rough-edged young girl who finds breeding and morals where she can, and triumphs over a mean fate with her inbred character. Robin Wright (from “Forrest Gump”) plays Moll as the kind of fierce survivor who doesn’t trust many men, but would follow the one she loves into the mouth of a cannon.

The movie is honest in its opening credits, which say it is “inspired” by the character in the 1722 novel by Daniel Defoe.

Virtually nothing from the book has been retained. Defoe’s famous title summarizes the original story: “The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders, &c. Who Was Born in Newgate, and During a Life of Continu’d Variety for Threescore Years, Besides her Childhood, was Twelve Year a Whore, Five Times a Wife [Whereof Once to her Own Brother] Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at Last Grew Rich, Liv’d Honest, and Died a Penitent.” In the movie version, written and directed by Pen Densham, Moll is barely 30 when the story ends, has been but One Time a Wife, has no brother, was not much of a thief, was never a felon and didn’t get to Virginia. I will give away less of the story than Defoe did and leave you in suspense over whether she grew rich, liv’d honest, &c.

What Densham does with the character is turn her into a woman who has been dealt a bad hand by life, but given the strength of character to play it. Along the way, like most of the heroes or heroines of 18th and 19th century British novels, she encounters a gallery of unforgettable characters, of whom three are crucial to her fate.

Mrs. Allworthy (Stockard Channing), the madam of the bordello, is a rich woman who recruits Moll (still a virgin) with a vision of a new career: “Some of the first men in London come through my door. Wouldn’t you like to have power over them?” Moll would. Hibble (Morgan Freeman), Mrs. Allworthy’s servant, begs her not to sell her body, but Moll insists she knows what she is doing. One day she’s hired to go to the rooms of a young man (John Lynch) and finds them stacked with cadaver parts; he isn’t a mass murderer but an artist who buys limbs for his study of anatomy. He hires her as a model, and their unlikely relationship grows into a fierce love and the first real happiness Moll has ever known.

This story is told entirely in flashback, as Hibble reads to Moll’s daughter, Flora, from Moll’s journal of her life story. Flora was separated from her mother during a period of crisis, and Hibble has spent many years tracking her down. Unlike many stories that begin at their ends, this one still manages to preserve a surprise, but the plot isn’t the point; this is a movie about atmosphere, personality and character.

Robin Wright never bends as Moll Flanders; you can never catch her trying to sweeten or smooth the edges of the character. Even lines like “I was the sparrow of hope, looking for a nest” are said not for poetic effect, but as simple reportage. The movie doesn’t sentimentalize its time. London is brutal for a young woman without means or protection, and Moll understands that and deals with it. There is even a certain sympathy in the movie’s treatment of Mrs. Allworthy, a hard businesswoman but a realist: Unattached, unsupported, uneducated and attractive women in London 250 years ago had few options, and the one offered by Mrs. Allworthy pays the best, and offers less chance of an early death.

Freeman’s character is intriguing. Who exactly is Hibble, and where does he come from? The West Indies, probably. His relationship with Mrs. Allworthy seems part servant, part confidante; his solicitude for Moll Flanders is touching, even if a little too kind to be supported by the times.

The Artist (he is never named) is played by Lynch as a fierce, sad young man who drives himself to a higher standard than he can achieve, and is inspired by Moll’s own defiant standards. The movie’s most amusing scene comes when the Artist proposes marriage, Moll insists on meeting his family, and they drive down to a vast country estate. A friendly man comes running up to greet their carriage. “Is that your father?” asks Moll. “You’re not going to get off that easy,” the Artist says, as the man opens the gate and doffs his cap.

“Moll Flanders” is not a sunny reconstruction of an idealized past, like “Sense and Sensibility.” It’s closer in historical detail to “Restoration” (both movies show the population devastated by plagues). As a story, it’s an original; Densham took only the name, the period, and a few notions from Defoe, and has made up the rest. Moll in many ways resembles Jenny, the character she played in “Forrest Gump.” Both stand aside from their societies, associate with outcasts and rebels, and do not confuse sexuality with romanticism. The film’s melodramatic ending sorts everything out in the approved style of the genre, but the movie is really better than that, a portrait of a woman who endures, thinks, and survives.