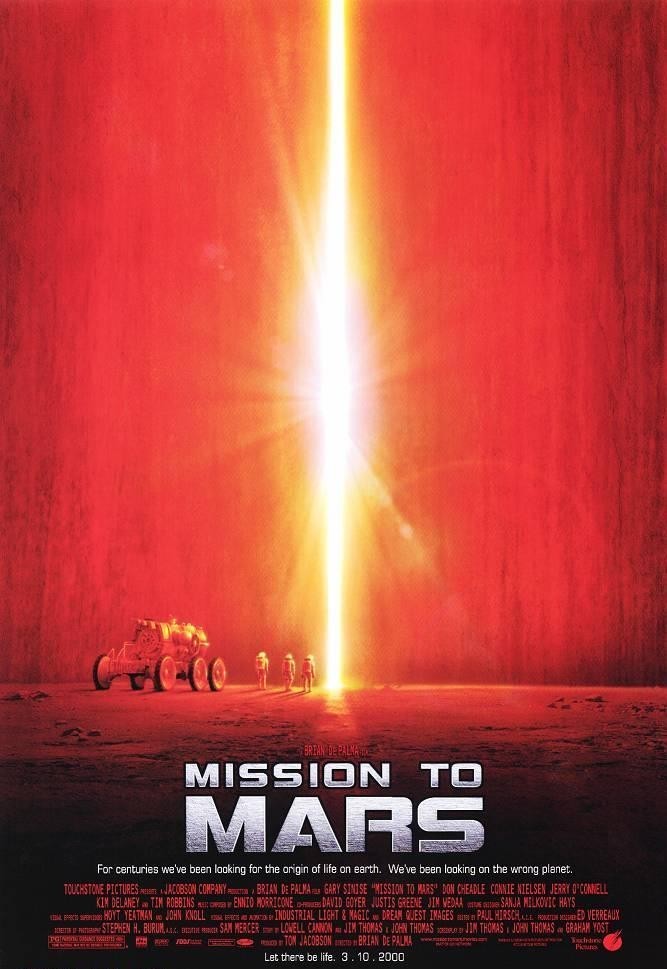

Well, here it is, I guess, a science-fiction movie like the one I was wishing for a few weeks ago in my review of “Pitch Black.” That film transported its characters to an alien planet in a three-star system and then had them chase each other around in the desert and be threatened by wicked bat-creatures. Why go to all the trouble of transporting humans millions of miles from Earth, only to mire them in tired generic conventions? “Mission to Mars” is smarter and more original. It contains some ideas. It also has its flaws. It begins with an astronaut’s backyard picnic that’s so chirpy, it could easily accommodate Chevy Chase. It contains conversations that drag on beyond all reason. It is quiet when quiet is not called for. It contains actions that deny common sense. And for long stretches the characters speak nothing but boilerplate.

And yet those stretches on autopilot surround three sequences of real vision, awakening the sense of wonder that is the goal of popular science fiction. The film involves a manned mission to Mars, which lands successfully and then encounters . . . something . . . that results in the death of three of the crew members, and loss of radio contact with the fourth (Don Cheadle).

A rescue mission is dispatched, led by co-pilots Tim Robbins and Gary Sinise, with Connie Nielsen as Robbins’ wife and Jerry O'Connell as the fourth member. They run into a clump of tiny meteorites, which punctures the spaceship’s hull and leads to a loss of air pressure. (It’s here that the Sinise character defies logic by refusing, for no good reason, to put on his helmet and draw oxygen from his suit.) Then there’s another crisis, which leads to a surprisingly taut and moving sequence in which the four characters attempt a tricky maneuver outside their ship and are faced with a life-or-death choice.

Arriving on the red planet, they find the survivor, hear his story and then are led into a virtual reality version of a close encounter of the third kind. They learn the history of Mars and the secret of life on Earth, and Sinise continues his journey in an unexpected way.

I am being deliberately vague here because one of the pleasures of a film like this is its visual and plot surprises. I like a little science in science fiction, and this film has a little. (The emphasis is on “little,” however, and its animated re-creation of the evolution of species lost me when the dinosaurs evolved into bison–and besides, how would the makers of that animation know the outcome of the process?) The movie also has some intriguing ideas and some of the spirit of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Not a lot, but some. (It pays homage to Kubrick’s film by giving us spacesuits and spaceship interiors that seem like a logical evolution of his designs.) I watched the movie with pleasure that was frequently interrupted by frustration. The three key sequences are very well done. They are surrounded by sequences that are not–left adrift in lackluster dialogue and broad, easy character strokes. Why does the film amble so casually between its high points? Why is a meditative tone evoked when we have been given only perfunctory inspiration for it? Why is a crisis like the breached hull treated so deliberately, as if the characters are trying to slow down their actions to use up all the available time? And why, oh why, in a film where the special effects are sometimes awesome, are we given an alien being who looks like a refugee from a video game? I can’t recommend “Mission to Mars.” It misses too many of its marks. But it has extraordinary things in it. It’s as if the director, the gifted Brian De Palma, rises to the occasions but the screenplay gives him nothing much to do in between them. It was old Howard Hawks who supplied this definition of a good movie: “Three great scenes. No bad scenes.” “Mission to Mars” only gets the first part right.