At first it’s a matter of a missed word, a forgotten name. Then he forgets how to drive a familiar route. The advertising executive keeps his worries to himself, but he can’t hide his problems, and eventually a doctor delivers a dread prognosis: Early- onset Alzheimer’s. He is only 49.

“Memories of Tomorrow” is the first movie I’ve seen about the disease that is told from the sick person’s point of view, not that of family members. The director, Yukihiko Tsutsumi, often uses a subjective camera to show the commonplace world melting into bewildering patterns and meanings. The subject of the film, Saeki, is a high-octane ad executive with a young and eager team, and as a perfectionist it depresses him to discover his own imperfections mounting. He forgets dates, times, business meetings. In one breathtaking scene, he gets lost in Tokyo’s urban maze and takes instructions from a secretary over his cell phone while literally running back to his office.

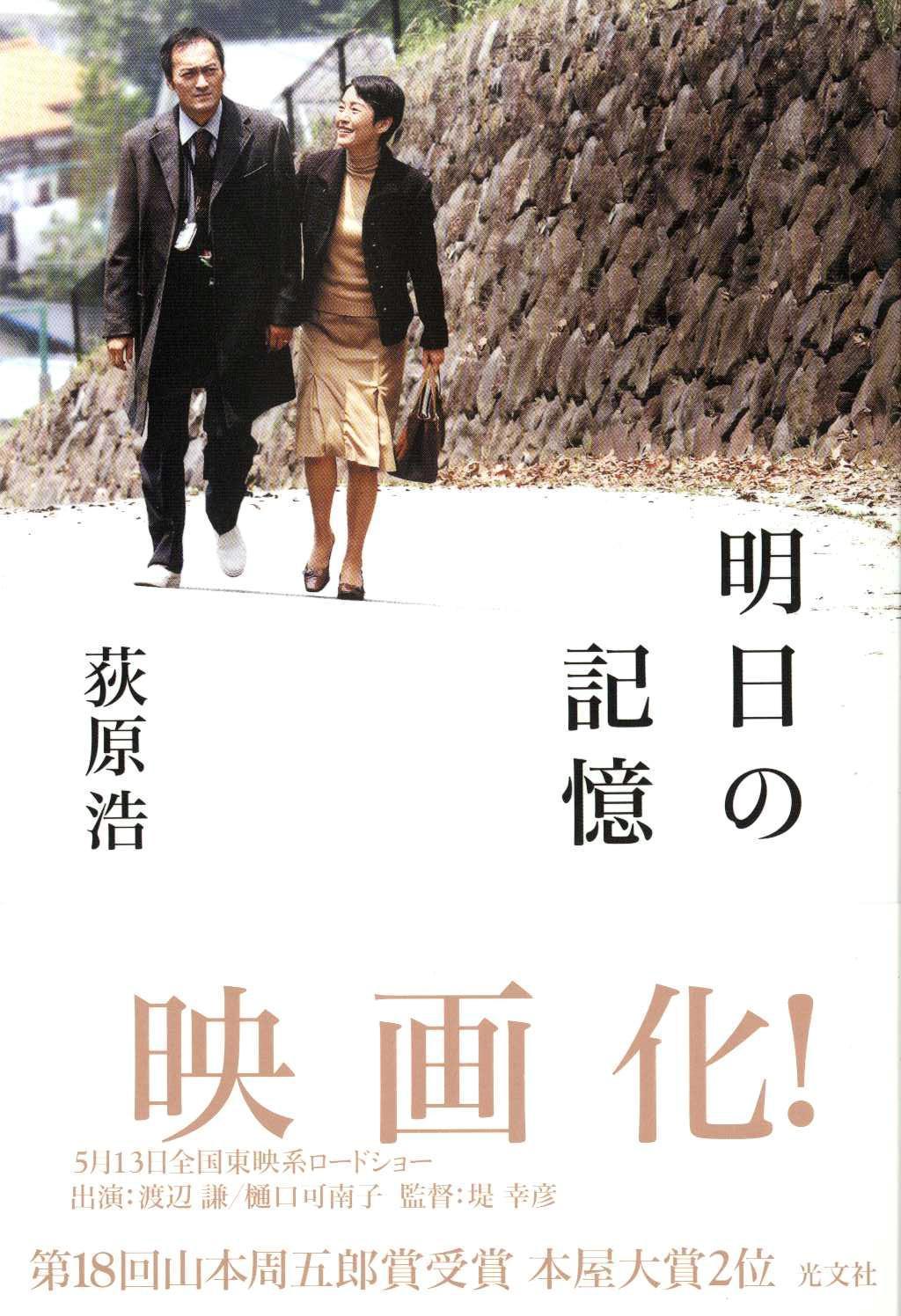

The character is played by Ken Watanabe (“Batman Begins,” “Memoirs of a Geisha,” “Letters from Iwo Jima”) and there is a personal element in his brave and painful performance. Watanabe is now 48, and since he was 30, I learn from the Japan Times, he has been fighting leukemia. His Saeki is just as determined to fight Alzheimer’s, and is much aided by his patient and courageous wife Emiko (Kanako Higuchi), who writes notes naming everything in their house, prepares his daily schedule, and keeps up a brave front.

He holds on as long as he can, even accepting a lesser position and a smaller pension to stay with his company, but finally he must retire, and return to a home where now it is his wife who goes out every morning to earn a salary. He has better days and worse days, and a day fraught with fear when he must make a speech at his daughter’s wedding. He loses the text of his speech. “Just say anything,” his wife whispers. “I’m here for you.” She takes his hand.

She has the patience of a saint, but one day he physically hurts her. The director handles this painful moment with great visual tact, not showing it but instead cutting to the sudden darting of fish in an aquarium. And then his wife snaps, telling him with cold anger what a distant husband he has been, how flawed, how cruel.

The movie isn’t structured like a melodrama, but reflects a slow fading of the light. There are moments of almost unbearable sadness, as in what he reveals to a nurse at the end of a tour of a nursing home. And we observe the indifference of the company where he has been a salaryman all his life: Yes, thanks for your contribution, now go quietly, please, and don’t let the clients know. Some films on Alzheimer’s attempt to show an upside. I don’t think there is an upside. At least with cancer you get to be yourself until you die.