[EDITOR’S NOTE: This review contains spoilers.]

McCabe rides into the town of Presbyterian Church under a lowering sky, dismounts, takes off his buffalo-hide coat, puts on his bowler hat and mumbles something under his breath that we can’t quite make out, but the tone of voice is clear enough. This time, he’s not going to let the bastards grind him down.

He steps off through the mud puddles to the only local saloon, throws a cloth on the table and takes out a pack of cards, to start again. His plan is to build a whorehouse with a bathhouse out in back, and get rich. By the end of the movie, he will have been offered $6,250 for his holdings, and he will be sitting thoughtfully in a snowbank, dead, as if thinking it all over.

And yet Robert Altman‘s “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” doesn’t depend on that final death for its meaning. It doesn’t kill a character just to get a trendy existential feel about the meaninglessness of it all. No, McCabe doesn’t find it meaningless at all, and once Mrs. Miller explains the mistake he made in his reasoning, he rides all the way into the next town to try to sell his holdings for half what he was asking, because he’d rather not die.

Death is very final in this Western, because the movie is about life. Most Westerns are about killing and getting killed, which means they’re not about life and death at all. We spend a time in the life of a small frontier town, which grows up before our eyes out of raw, unpainted lumber and tubercular canvas tents. We get to know the town pretty well, because Altman has a gift for making movies that seem to eavesdrop on activity that would have been taking place anyway.

That was what happened In “MASH,” where a lot of time didn’t have to be wasted in introducing the characters and explaining the relationships between them, because the characters already knew who they were and how they felt about each other. In a lot of movies, an actor appears on the screen and has no identity at all until somebody calls him “Smith” or “Slim,” and then he’s Smith or Slim.

In “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” Altman uses a tactfully unobtrusive camera, a distinctive conversational style of dialog and the fluid movements of his actors to give us people who are characters from the moment we see them; we have the sense that when they leave camera range they’re still thinking, humming, scratching, chewing and nodding to each other in the street.

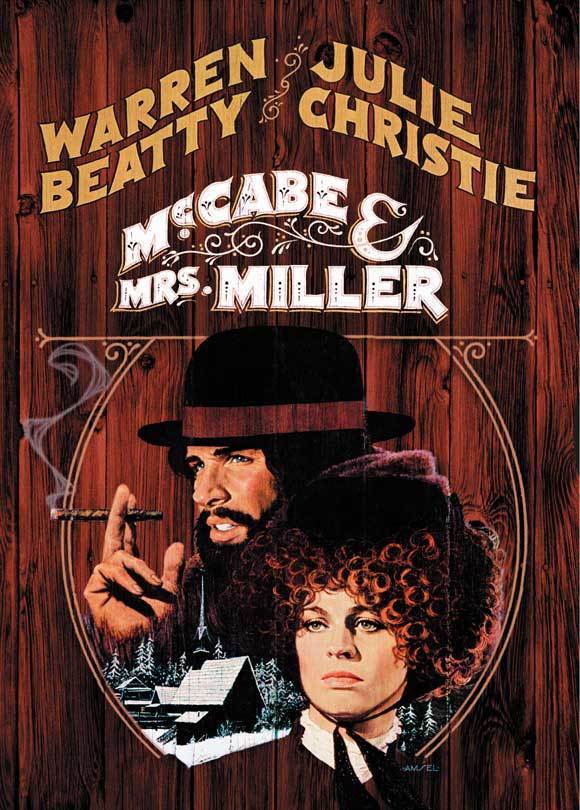

McCabe and Mrs. Miller are an organic part of this community. We are aware of course, that they’re played by Warren Beatty and Julie Christie, but rarely have stars been used so completely for their talents rather than their fame. We don’t ever think much about McCabe being Warren Beatty, and Mrs. Miller being Julie Christie; they’re there along with everybody else in town, and the movie just happens to be about their lives.

Because the movie is about a period in the lives of several people (and not about a series of events that occur to one-dimensional characters), McCabe and Mrs. Miller change during the course of the story. Mrs. Miller is a tough Cockney madam who convinces McCabe that he needs a competent manager for his whorehouse: How would He ever know enough about managing women? He agrees, and she lives up to her promise, and they’re well on their way to making enough money for her to get out of this dump of a mining town and back to San Francisco where, she believes, a woman of her caliber belongs.

All of this happens in an indoor sort of a way, and by that I don’t mean that the movie looks like it was shot on a sound stage. The outdoors is always there, and people are always coming in out of it and shaking the rain from their hats, and we see the trees whipping in the wind through the windows.

But it’s a wet autumn and then a cold winter, so people naturally congregate in saloons and grocery stores and whorehouses, and the climate forces a sense of community.

Then the enforcers come to town: The suave, Scottish-accented Butler, who kills people who won’t sell out to the Company, and his two sidekicks. One of them is slack-jawed and mean, and the other is a nervous blond kid with the bare makings of a mustache. On the suspension bridge that gets you across the river to the general store, he kills another kid a rawboned, easygoing country kid with a friendly smile — and it is one of the most affecting and powerful deaths there ever has been in a Western.

The final hunt for McCabe takes place in almost deserted streets, because the church is burning down and everybody is out at the edge of town trying to save it. The church burns during a ghostly, heavy daylight snowstorm: fire and ice. And McCabe almost gets away. Mrs. Miller, who allowed him into her bed but always, except once, demanded $5 for the privilege, caught on long before he did that the Company would rather kill him than go up $2,000. She is down at the foot of town, in Chinatown, lost in an opium dream while the snow drifts against his body. “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” is like no other Western ever made, and with it, Robert Altman earns his place as one of the best contemporary directors.