The Rodney Bingenheimer of today seems always to be smiling through a deep sadness. He is a small man who still has the youthful cuteness that must have won him friends in his early days. His hair is still combed in the same tousled mid-1970s rock star style, and his T-shirts are the real thing, not retro. He lives now in an inexpensive apartment jammed with records, tapes, discs, and countless autographed photos of his friends the stars. And, yes, they are still his friends; they have not forgotten him, and David Bowie, Cher, Debbie Harry, Courtney Love, Nancy Sinatra and Mick Jagger all appear in this film and seem genuinely fond of Rodney.

Well they might. He introduced some of them — Bowie in particular — to American radio. He was known for finding new music and playing it first: The Ramones, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, Nirvana. Stations all over the country stole their playlists from Rodney. “Sonny and Cher were kinda like my mom and my dad,” he says wistfully at one point. He ran a little club for a while, featuring British glam rock, and the stars remember with a grin that it was so small the “VIP Area” consisted simply of a velvet rope separating a few chairs from the dance floor.

The story of how Bingenheimer entered into this world is apparently true, unlikely as it sounds. As a kid he was obsessed with stars, devoured the fan magazines, collected autographs. One day when he was a teenager, his mother dropped him off in front of Connie Stevens’ house and told him he was on his own. He didn’t see his mother for another five or six years. Connie wasn’t home.

He migrated to the Sunset Strip, but instead of dying there or disappearing into drugs or crime, he simply ingratiated himself. People liked him. He hustled himself into a job as a gofer for Davy Jones of the Monkees (they looked a little alike), and then became a backstage caterer; a survivor of a Doors tour remembers a Toronto concert where Rodney had enormous platters of fresh shrimp backstage. But the Beatles were backstage visitors, and Rodney gave them the shrimp, so there were only a few left for the Doors, who had paid for them. Challenged by The Doors, Rodney shrugged and said, “Well, they’re the Beatles.”

Wherever Bingenheimer went in the music and club scene, his face was his passport. Robert Plant says, “Rodney got more girls than I do.” We hear a little of his radio show from the old days, and what comes across is not a vibrating personality or a great radio voice — it’s kind of tentative, really — but an almost painful sincerity. He loves the music he plays, and he introduces it to you like a lover he thinks is right for you.

The road downhill was gradual, apparently. We get glimpses of Rodney today, repairing his mom’s old Nova with a pair of pliers, shuffling forlornly through souvenirs of his glory days. He seems very even, calm, sad but resigned, except for one moment the documentary camera is not supposed to witness, when he finds that another deejay, a person he sponsored and gave breaks to, is starting a show of new music — stealing Rodney’s gig. He explodes in anger. We’re glad he does. He has a lot to feel angry about.

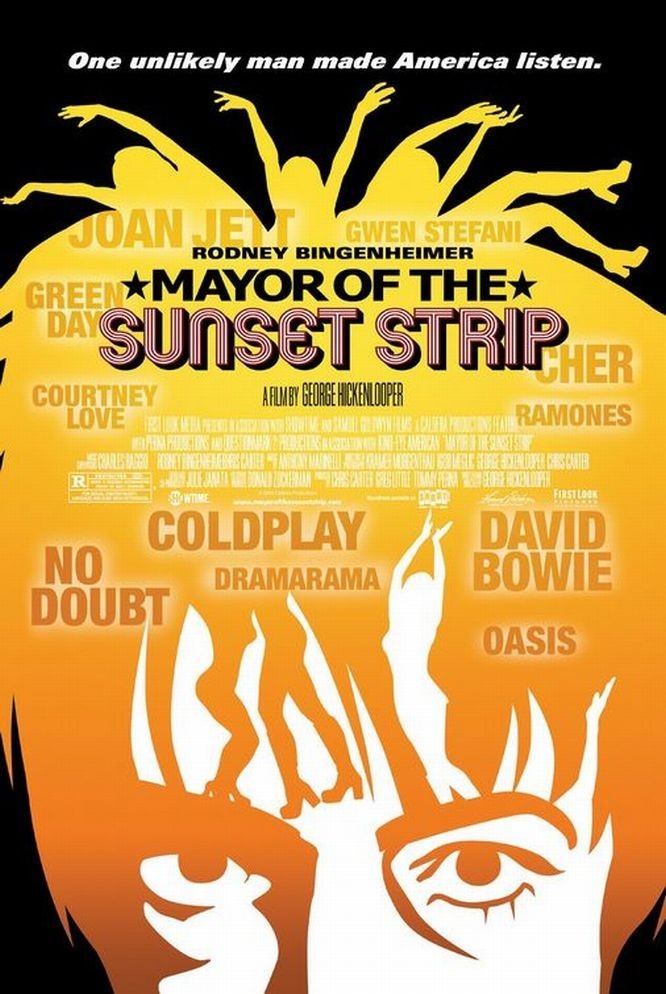

The film was directed by George Hickenlooper, who made the classic doc “Hearts Of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse” (1991), about the nightmare of Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now,” and the wonderful fiction film “The Man From Elysian Fields” (2001). Why did he make this film (apart from the possibility that someone named Hickenlooper might feel an affinity for someone named Bingenheimer)? Hickenlooper has been around fame at an early age. He was 26 when he released the doc about the Coppola meltdown. He cast Mick Jagger and James Coburn in “Elysian Fields.” He was aware of Rodney Bingenheimer when the name still opened doors. His film evokes what the Japanese call mono no aware, which refers to the impermanence of life and the bittersweet transience of things. There is a little Rodney Bingenheimer in everyone, but you know what? Most people aren’t as lucky as Rodney.