“It is so complicated to talk about my mom, but she is where my strength comes from. My mother had me when she was sixteen years old, and she was an orphan by the time she was ten. She was the first person to ever love me completely and the first person to ever reject me wholly. We grew up together, so much so that people thought we were brother and sister.”

This is what writer/director Elegance Bratton told me during our recent interview about his achingly personal debut feature, “The Inspection,” which is based on his own experience of discovering his inner strength while serving in the Marine Corps. His sense of worthlessness was instilled in him by his mother, who rejected him after learning he was gay, yet that betrayal did not stop Bratton from loving her or wanting to mend their relationship. He knew that it was the strength she harnessed to bring him into the world and care for him, despite all the odds stacked against her, that fueled his endurance in his journey toward self-acceptance.

His story echoes that of George Anthony Morton, the subject of Rosa Ruth Boesten’s haunting HBO documentary, “Master of Light,” who details how his mother had him at the mere age of fifteen and was like a sister to him. She only knew how to provide for her child by selling drugs, a lifestyle that resulted in George being locked away for over 11 years in federal prison, and robbed of the entirety of his twenties for possessing two ounces of crack cocaine. Only years after his release do his siblings inform him that his mother may have set him up to serve time. It’s the sort of betrayal that other films would select as its chief focus, but “Master of Light” is about the rebuilding of a life rather than the destruction of one. As Morton instructs his young nephew, “I am not what has happened to me, but what I choose to become.”

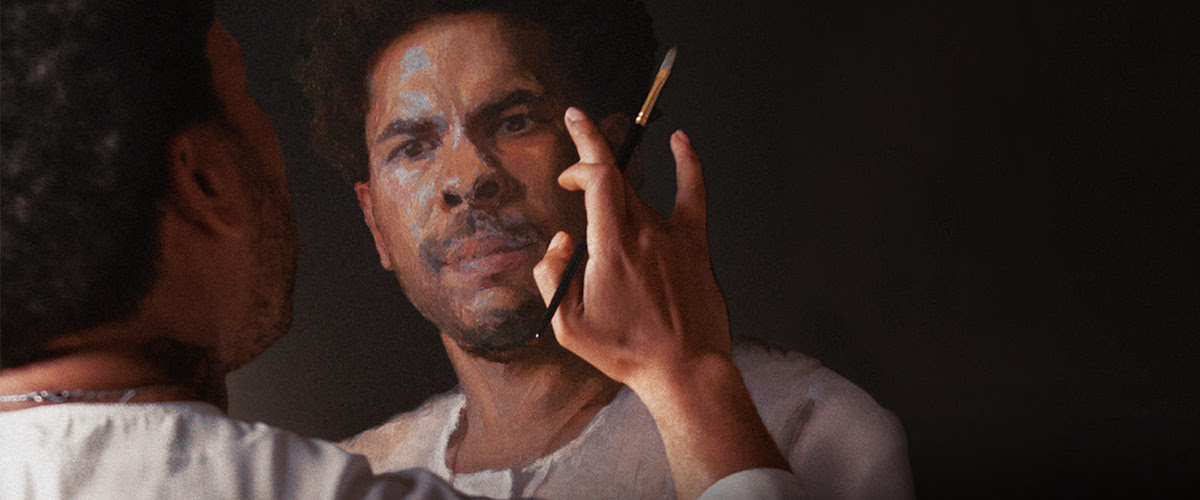

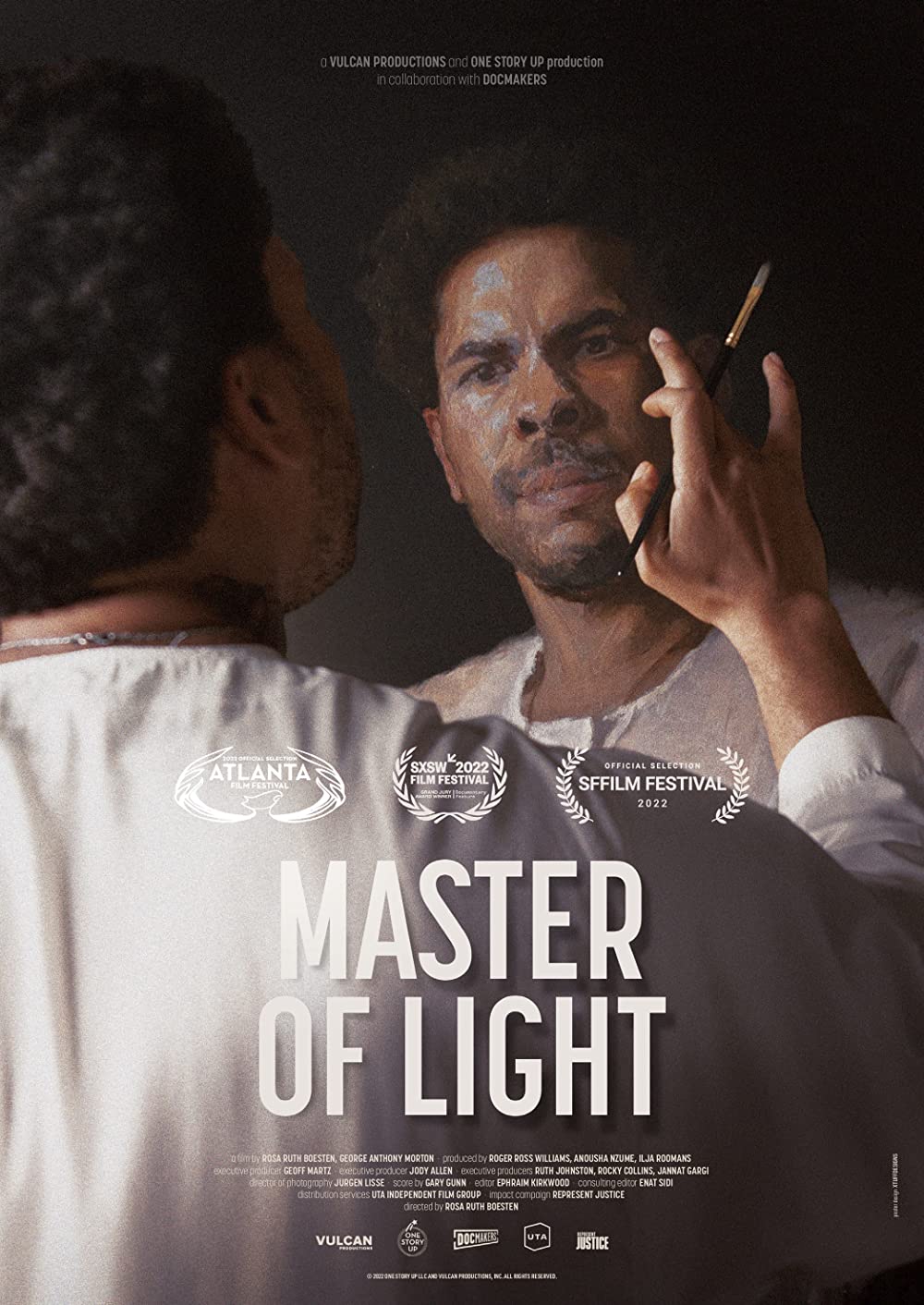

Just as Bratton funneled his pain into his artistry, Morton spent his years behind bars honing his craft as an extraordinary painter in the tradition of his artistic inspiration, Rembrandt. The film itself is gorgeously lensed by Jurgen Lisse, who plays with the duality of light and darkness expressed throughout both the work and personal struggles of Morton, as he straddles the line between occupying the art world and the impoverished existence of his mother. Yet Boesten and her editor Ephraim Kirkwood also structure the film like a portrait that only gradually reveals itself as each detail is added to the canvas.

Aside from a couple of title cards specifying locations such as Morton’s birthplace of Kansas City, Missouri, the film never places onscreen the names of Morton’s family members or specifies their relationship to one another, leaving us to rely on our listening skills to complete the family tree. By the film’s final moments, we feel as if we have reached a clearer understanding of each person from Morton’s life that he has chosen to paint, including his devoted partner Ashley, whose upbringing was entirely different from Morton’s, which occasionally causes friction between them as she warns him against aiding his self-destructive mother.

The film’s co-producer, Roger Ross Williams, directed one of the most astonishing films I’ve seen about the transformative power of art, 2016’s “Life Animated,” which explores how Disney films helped an autistic man connect with the surrounding world that had once seemed out of reach. “Master of Light” is every bit as profound and insightful in illuminating how painting has had a therapeutic role in Morton’s life, enabling him to grapple with his anger at a system designed to entrap people in his situation. His stated aim is to carry into the future artistic traditions that “people of African descent have not had a dignified part in” over the past centuries.

There’s a striking 360-degree pan around Morton walking through an art museum as he finds himself surrounded by the framed faces of Caucasians. He compares his experience of finding himself shackled up in Oklahoma to being on an auction block as his prison was selected for him. Many of the film’s most moving moments center on Morton’s interactions with his nephew, who expresses his fear in light of the horrific murders of Black people at the hands of police that fueled the Black Lives Matter movement. Morton argues that it is, in fact, white perpetrators such as these who fear the giant within people like his nephew who has now woken up, and it’s wonderful to see the budding young artist penning rap songs as a way of tackling his demons.

As I watched Boesten’s film, I kept being reminded of what Bratton had to say to me about finding strength in forgiveness. “If I had held onto everything that happened, I wouldn’t be here,” he told me. “I would be upset somewhere in a bar, mad at the world.” I imagine Morton feels the same way, and indeed, there is a moment in “Master of Light” in which it appears that he is ready to sever his ties with his mother for good, enraged at her seeming efforts to halt him from succeeding in life. Yet he later tells his therapist that he ultimately wants to believe his mother, who denies her children’s accusations that she sent her son to jail in exchange for avoiding her incarceration. In many ways, this film would make a hugely rewarding double bill with Bratton’s “The Inspection,” considering how both films take an uncommonly frank and unsentimental look at how one can persevere in the face of rejection.

“Is it not evident that there was some beauty in the ugliness of all this?” asks Morton during the film’s final moments, just before us seeing the beauty on full display upon his canvas. It is there in the face of his mother, whose own desire to love and be loved brought him to this earth and drove her refusal to let him go, even with the countless obstacles and inequities she faced daily. Boesten’s picture leaves viewers contemplating all that they have been unwilling to forgive, and all that could be achieved once that baggage has been thrust from their shoulders.