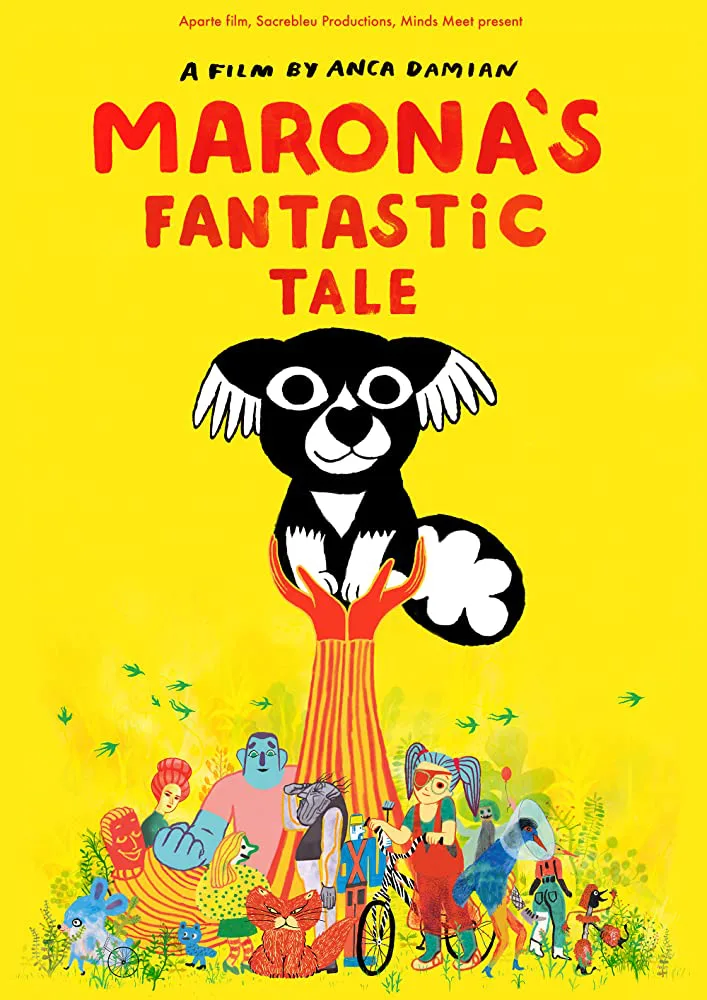

The title “Marona’s Fantastic Tale” promises a fantasy or fable, packed with dream visions, eccentric characters and world-changing events. But while this animated film from director Anna Damian delivers all that and more, nothing that happens in it would seem extraordinary if you were describing it to a friend. It’s about the chaotic life of a pet—a mixed breed dog who calls herself a “mutt”—and there isn’t a single thing in it that couldn’t happen.

Because Damian and her collaborators tell this story subjectively, through first-person narration and images that shift, warp, and pulse according to the dog’s perceptions, you arrive at the end of “Marona’s Fantastic Tale” realizing you haven’t just been taken on a journey, but made to appreciate it in ways you wouldn’t have, if it were told conventionally. This movie appreciates the difficulties animals must have navigating a world dominated by humans. It asks viewers to appreciate what’s important to a dog, and how mammals with short life spans might perceive time, relationships, and memory.

None of this stuff is on the minds of most other animated films about pets, except in a lighthearted and superficial way, because the second a storyteller decides to take a dog’s life as seriously as a human’s, and think about them as independent beings rather than avatars for humans, the story ceases to be escapism, and becomes a psychological drama about philosophical and spiritual questions that have no clear answers.

And that’s what “Marona’s Fantastic Tale” ultimately becomes, although it’s funny and exciting along the way, and often beautiful and surprising. Films about dogs, cats and other household animals tend to labor to convince us their main characters are just people in animal costumes—often wisecracking ones with celebrity voices. Sometimes they give them office jobs and gendered clothes and human responsibilities, and have them make jokes about pop stars and presidents and mortgages and school admissions, because that’s the joke, ha ha. Those films were never worth much, but they seem small indeed after watching “Marona’s Fantastic Tale,” the “Remembrance of Things Past” of animated dog movies.

It’s important to know before queuing up this film for a birthday party that even though “Marona’s Fantastic Tale” is an animated picture about a lovable dog, and is designed and directed with dazzling showmanship and anchored in compassion, it is not a film you can show to small children without first gauging if they’re patient, open-minded, and mature enough to make sense of it. Marona is a bit like the doggie cousin of a juvenile narrator from an early Terrence Malick movie like “Badlands” or “Days of Heaven,” struggling to make sense of a world she can’t fully understand. A charming running gag finds Marona explaining that her relationship with one owner revolves around him taking her out to a field and throwing a ball and her bringing it back to him, because it’s the throwing part that really interests him, you see. But where cognitive ability fails, instinct fills the gap. “Dogs can smell when something bad is brewing, when our human has a heavy conscience,” she confides, right before one of her owners hands her off to someone else.

However—this is important, and not a spoiler, as Damian establishes this in the very first scene—you should be forewarned that the entire story is a deathbed flashback, recounted in the moments after Marona is hit by a car. This is something that we all know happens to dogs, all the time. But most animated films don’t dare show it, for fear it would traumatize children and make their parents demand a refund and post angry reviews on Amazon. It’s much more likely that a dog film will exploitatively tantalize us with the possibility that a dog will die onscreen, then reveal at the last second that it lived, and perhaps show it commiserating with animal pals while limping on an adorable little crutch.

Marona’s demise not gory or even particularly blunt. In fact, the filmmakers go out of their way to cushion the blow, by showing it in an abstract way, telling us from the opening that this is how Marona will go, then backing up to tell us her whole life story, including her early experiences with her mother and father and eight siblings, and with various human caretakers, some attentive, others neglectful or mean.

Her first owner is an acrobat, drawn as an impossibly long, slender being defined by wavy, elastic lines. Her second owner is a big, deep-voiced delivery truck driver who loves Marona but is more enamored with, and loyal to, his girlfriend, a petty, vain woman who thinks of Marona as a lifestyle accessory and acts as if she’s competing with the dog for his attention. Then there’s the deliveryman’s elderly mother, who is sweet during daytime but turns scary at night. Finally there’s a young girl who finds Marona in a park and takes her home to her mother and grandfather. The girl raises Marona to adulthood, faltering only when she becomes a teenager and disappears into herself, as teenagers tend to do.

None of these human characters, including the “good” ones, are presented as entirely noble individuals, because their flaws are what make them, well, human. The closest thing to a purely good person is the girl’s mother, a harried single mom distracted by financial troubles and the responsibility of caring for her elderly and disabled father; she is literally overflowing with love, her long, red hair sometimes seeming to extend beyond her feet and wrap around her daughter like a superhero’s cape. (It grows longer the more openly she expresses love and concern.)

Part of the point is to encourage us to look at ourselves as the caretakers of pets, or the loved ones of humans who are caretakers of pets, then ask if we set the kind of example that we should, or if we could try harder, pay more attention, think about something other than ourselves. It all feels rather like a self-delivered eulogy or obituary by a person who lived a life that a historian or media outlet would not consider significant enough to acknowledge, but that meant a great deal to her and to the people she was close to. The movie falls within the cinematic tradition of stories narrated by people who have just died and are trying to make sense of their lives as they pass from one plane to the next.

One of the most extraordinary sequences shows Marona witnessing a human’s death—not just the cessation of bodily functions, but the release of the soul and the transformation of matter into energy, accompanied by a spiral ramp (like a DNA helix) appearing in the air above the body. In addition to confirming that our pets can, in fact, see beyond this realm, and sense spirits as they pass between worlds, a deeply reassuring thought, the scene serves as a final brake against the impact of what we know is coming. Marona may be gone from this plane, but we know she’s headed somewhere else. That makes the ending not bitter, but bittersweet.

“Marona’s Fantastic Tale” is demanding in terms of its style, its tone, and choice of what to emphasize and how to show it to us. It is not an American studio-type of animated production, with three-dimensional-looking, realistically shaded drawings; visual grammar that mimics live action Hollywood blockbusters; a soundtrack of brash, Broadway-ready original songs or needle-drop pop tunes, and dialogue packed with cultural references and slang that must have seemed cutting-edge when the project was green-lit five years earlier. The movie unfolds according to its own logic and intuition and demands a great deal of adults as well as kids, starting with the basic proposition that life is finite and ends in death, you don’t get to choose the time, place, and circumstances of your passing, and it’s not only OK for animation to talk about these things, it’s healing.

If you read that last sentence and thought, “This sounds very French,” well, yes: this is a French-Romanian coproduction, and while it might seem like overdoing it to call the movie existential, the word fits. This is a movie about existence, about the necessity of moving through life as best you can knowing that everybody gets the same ending. And it’s about the ordinary, often wrenching truth of what it means to live, age, and die, leaving behind a legacy of love and regret, if not always children or grand achievements. When you hear the phrase “a dog’s life,” it is often framed in a sad, dismissive or smug, way, as in, “I wouldn’t wish that kind of life on a dog.” But what does that say about the value that humanity actually places on dogs? A dog’s life and a human’s are equally valuable to the creature who’s living it. The dog is smaller and doesn’t live as long and can’t operate a doorknob.

“Finally,” Marona says, snuggling into the home of caretakers who actually take care of her, “humans who understand what it means to be a canine.” Finally, too: a cartoon that appreciates dogs as dogs, and treats one dog’s life with the gravity we’d want expressed at a memorial for a human of no importance who meant everything to us.

Available in virtual cinemas today, 6/12.