Some kids beat him up once and he couldn’t stop them. Another kid killed one of his homing pigeons, and he fell upon him with fury. And that is the back story of Mike Tyson, a boxer known as the Baddest Man on the Planet. When he went into the ring, he was proving he would never be humiliated again and getting revenge for a pigeon he loved.

I believe it really is that simple. There is no rage like that of a child, hurt unjustly, the victim of a bully.

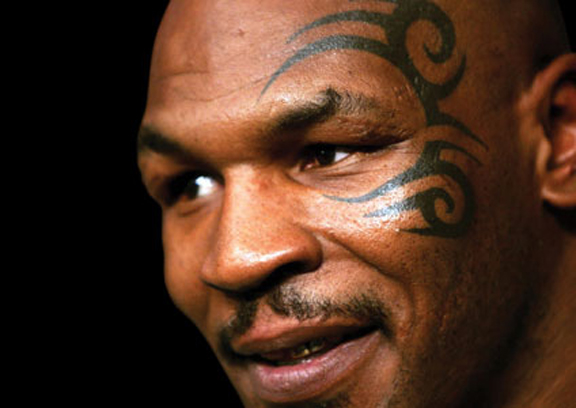

James Toback’s “Tyson” is a documentary with no pretense of objectivity. Here is Mike Tyson’s story in his own words, and it is surprisingly persuasive. He speaks openly and with apparent honesty about a lifetime during which, he believes, he was often misunderstood. From a broken family, he was in trouble at a tender age and always felt vulnerable; his childhood self is still echoed in his lisp, as high-pitched as a child’s. It’s as if the victim of big kids is still speaking to us from within the intimidating form of perhaps the most punishing heavyweight champion of them all.

Mike Tyson comes across here as reflective, contrite, more sinned against than sinning. He can be charming. He can be funny. You can see why Toback, himself a man of extremes, has been a friend for 20 years. The film contains a great deal of fight footage, of Tyson hammering one opponent after another. We also see a TV interview, infamous at the time, of his ex-wife Robin Givens describing him as abusive and manic-depressive. Even then I wanted to ask her, “and who did you think you were marrying?”

Tyson freely admits he has mistreated women and says he regrets it. But he denies the rape charge brought against him by Desiree Washington, which led to his conviction and three years in jail. “She was a swine,” he says. He also has no use for boxing promoter Don King, “a slimy reptilian [bleeper].” His shining hero is his legendary trainer Cus D’Amato, the man who polished the diamond in the rough from his early teens and died a year before Tyson’s first heavyweight crown.

“Before the fight even starts, I’ve won,” Tyson says. From Cus, he learned never to take his eyes from his opponent’s face from the moment he entered the ring. So formidable was his appearance and so intimidating his record that it once seemed he would have to retire before anyone else won the title. But he lost to Buster Douglas in Japan in 1990 — the result, he says, of not following Cus’ advice to stay away from women before a fight. He went into the ring with a case of gonorrhea. Later losses he attributes to a lack of physical training at a time when he signed for fights simply for the payday. And there was drug abuse, from which he is now recovering.

In a career of directing many fine films (“When Will I Be Loved,” “Harvard Man,” “Fingers”), this is only Toback’s second doc. In 1990, he was sitting next to a businessman on a flight and convinced him to finance “The Big Bang,” in which he would ask people about the meaning of life, the possibility of an afterlife and what they believe in. “Tell me again why I’m financing this cockamamie thing?” the man asks him. Toback says, simply, that the film will be remembered long after both he and the man are gone.

Toback is remarkably persuasive. He was offering immortality. It is a tempting offer. In ancient Egypt, an architect named Toback must have convinced a pharaoh to erect the first pyramid. What he offered Tyson was the opportunity to vindicate himself. There is no effort to show “both sides,” but in fact the case against Tyson is already well known, and what is unexpected about “Tyson” is that afterward we feel sympathy for the man, and more for the child inside.

Read Chaz Ebert’s blog about “Tyson” from Cannes 2008: http://budurl.com/jfk7