In a key scene of “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom,” a new biopic about South African leader Nelson Mandela, a judge tells Mandela (Idris Elba) that he’s being sentenced to life imprisonment so that he can’t become a martyr. Mandela says he’s willing to die for his cause, and the judge replies, “I will not give you that satisfaction.”

The makers of “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom” did what that judge refused to, though for very different reasons: they let their admiration for Mandela’s suffering define their drama.

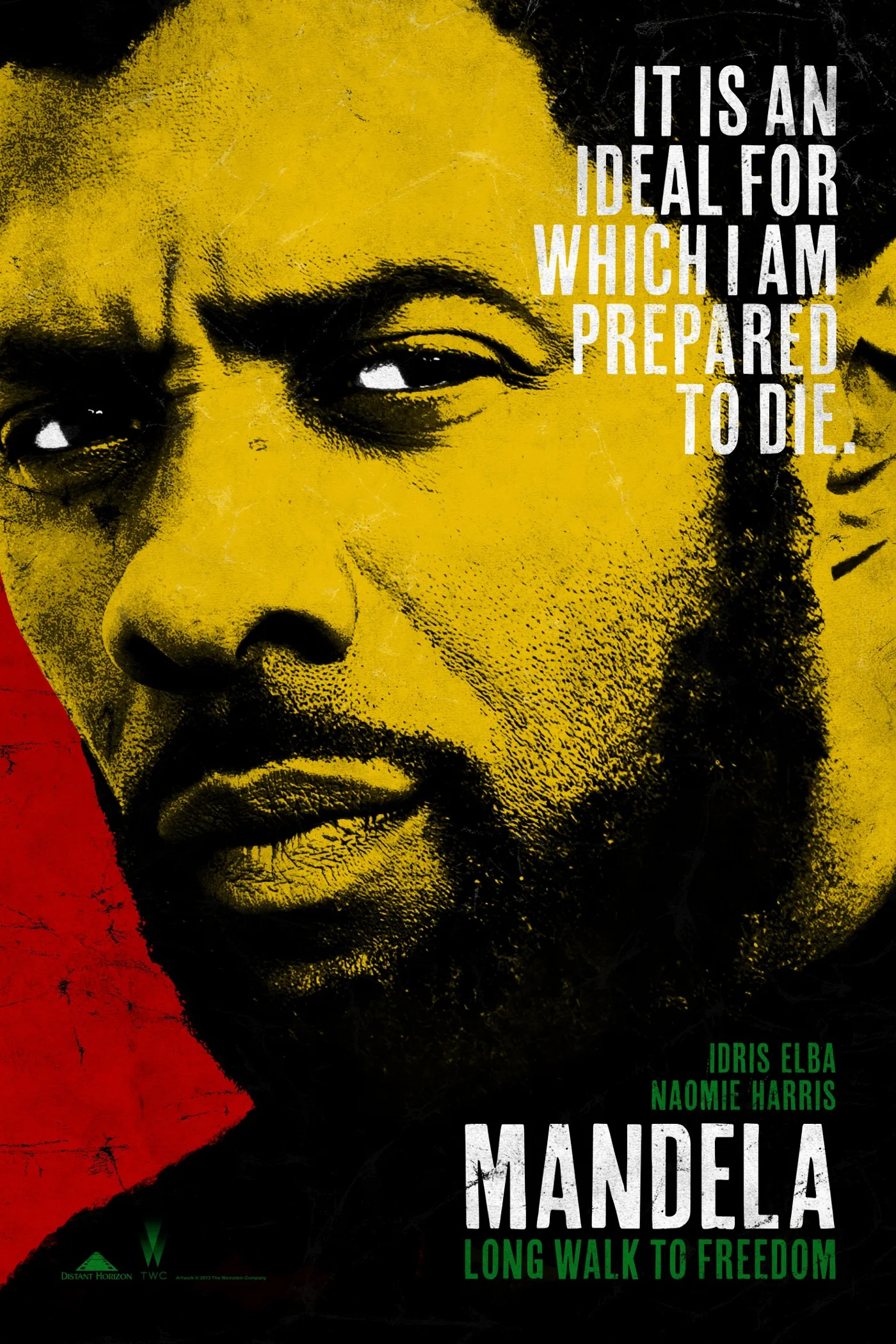

The film reduces Mandela’s ideas to impassioned sloganeering, and the repercussions of his ideas to unmoving montage sequences. It emphasizes his 27-year imprisonment as the foundation of his credibility, making the dense layers of make-up that are used to make a typically captivating Idris Elba the proof of his character’s struggle. The makers of “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom” have good intentions, but they don’t effectively dramatize what they think makes their subject great.

Mandela’s life in “Long Walk to Freedom” is defined by pained optimism. As a young lawyer, Mandela petitions for equality from a government that he soon discovers is only selectively fair. But that changes after a friend is beaten mercilessly just because he’s drunk, feels queasy and lacks proper documentation. This incident is poorly dramatized, happening in a flash. But it’s supposed to have a profound effect on Mandela. It leads him to agitate with like-minded individuals for the formation of an African National Congress (ANC). With these peers, he moves crowds to protest with his speeches. His oration is that much more powerful because of Elba’s delivery; if I could vote to put Elba in office, I would stuff the ballot boxes.

Up until his trial and imprisonment, Mandela is treated as a hallowed figure. This is in spite of the filmmakers’ half-hearted attempts to make him appear human. He is shown having an affair with a woman, but that subplot is only important in that it adds pathos to his story; it suggests that Mandela has skeletons in his closet that the movie isn’t inclined to examine. Still, Mandela is a romantic icon, and the makers of “Long Walk to Freedom” understandably treat him as such. His voice cuts through the garbled voices of white radio announcers, the ones who make major events like the Sharpeville Massacre sound distant and unreal. The ANC’s protests are filmed with context-free awe. So when a political office is blown up, you can enjoy the spectacle while effectively ignoring Mandela when he says that he is “not a violent man” but will use violence as a means to an end.

That disjointed characterization persists throughout the stretch of “Long Walk to Freedom” that covers Mandela’s imprisonment. This is especially true of the film’s depiction of Nelson’s rocky relationship with wife Winnie (an equally impressive Naomie Harris). She’s repeatedly arrested under suspicion of being involved with the ANC, and her resulting frustration grows throughout her brief visits to the prison. The prison guard insists that Nelson and his wife should not talk about poltiics, and “Long Walk to Freedom”‘s creators honor that request. Instead, they talk about how they feel about politics. So the raised tone of Winnie’s voice is more important than the content of her words.

Nelson and Winnie are supposed to have a complicated relationship, but it’s really only a muddled one. When the hero laments that he hasn’t touched his wife in 21 years, his face is obscured by a chain-link fence. It’s obvious what viewers are supposed to feel in this moment, but the scene itself just isn’t very moving.

The one aspect of “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom” that almost saves the film is Elba and Harris’s extraordinary charisma. She’s good enough to bring complexity to the scene where Winnie, drink in hand, gazes admiringly at Nelson as he delivers a televised address. And he’s just as impressive, especially when he has to make soundbite-friendly speeches about group unity, and the necessity of making compromises. These actors as good as their characters require them to be, but nothing else in “Long Walk to Freedom” is.