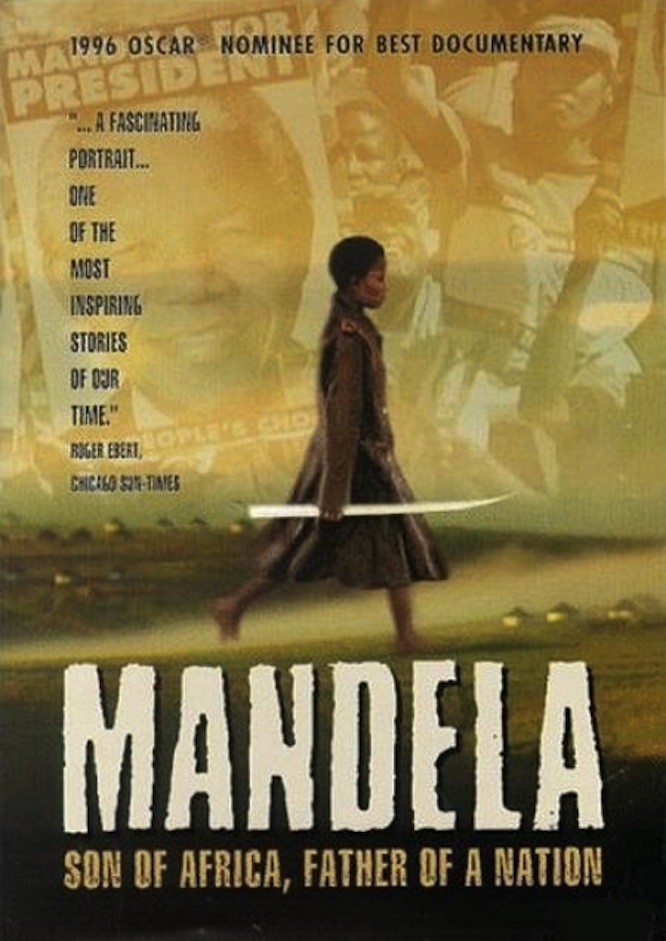

“Mandela,” a new documentary, nominated for an Oscar this year, charts his life from obscure beginnings to the Nobel Prize. It focuses on his steadfast vision of a multiracial South Africa where all would live together peacefully. When I spent 1965 as a student at the University of Cape Town, most people, black and white, believed the apartheid system would end in a bloody civil war. That there was a peaceful, democratic exchange of power is a tribute above all to Mandela’s moral leadership.

But that transfer of power also came about because of the courage and imagination of F. W. de Klerk, the white South African president who freed Mandela from prison, lifted the ban on the ANC and then ran against Mandela in a general election–and lost, as he knew he would. The two shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993.

I mention de Klerk because this film essentially writes him out of the story; it so simplifies the transfer of power in South Africa that it plays more like a campaign biography than a documentary. Why did de Klerk arrive at his decision? Civil unrest and international economic sanctions forced his hand, we are told, and then we see de Klerk informing the South African Parliament that his government had reached an irreversible decision to free Mandela and hold multiracial elections.

The actual story of the events leading to the election is more complicated and interesting. Yes, South Africa suffered from economic sanctions. But it could have survived for many years before caving in; it forged clandestine trading arrangements with countries ranging from China to Israel, and its diamonds still found their way onto the fingers of brides all over the world. Civil unrest was widespread, but South Africa had a fearsome array of police and military forces to counter it. If white South Africa had been adamant, apartheid would still be law.

What happened was a political miracle. Mandela’s unswerving moral and political strength coincided with the growing conviction within the ruling Nationalist Party (and its secret lodge, the Broderbund, and the quasi-official Dutch Reformed Church) that apartheid was, simply, wrong. While de Klerk’s predecessor, Pieter W. Botha, pledged eternal white defiance, de Klerk and other younger ministers instituted secret contacts with Mandela, and the new future of South Africa was hashed out in meetings over a period of years.

De Klerk, when he became president, wanted to free Mandela immediately. Mandela insisted that he be “the last man off” Robben Island; his colleagues and fellow political prisoners had to be freed first, and the ANC had to be recognized as a legitimate political party, not a terrorist underground.

Mandela, essentially running a government in exile, moved into the prison warden’s house and often made secret trips elsewhere in South Africa. One famous story tells of a hot day when Mandela’s government driver stopped outside a store to buy cold soda, and the world’s most famous political prisoner was left alone in the car. He could have simply walked away. But he realized he was more useful to the cause as a prisoner.

None of those events are told in “Mandela,” which simplifies the transfer of power into a fable of black against white; it all but implies that de Klerk was unwilling to see power change hands. The hope for the new South African future lies in multiracialism; its foundation story is a good place to start.

Still, what a fascinating portrait this film paints of Mandela! Named “Nelson” by a teacher who did not like his tribal name, Mandela was one of nine children of a polygamist father who had four wives (how did Mandela feel about that? The movie doesn’t ask). When his father died, the bright boy was adopted by a chief and prepared to become counselor to the king. He ran away to Johannesburg in the early 1940s to escape an arranged marriage and had soon moved into the Soweto Township home of Walter Sisulu, who with Oliver Tambo would join him in leading the ANC.

Mandela worked hard to support himself while studying law, became a lawyer and was soon a key leader of the ANC. His cause was never “black power,” but “one man, one vote.” That led him to Robben Island, and for 13 years he did hard labor in a limestone quarry while continuing to lead prison classes and discussion groups.

The film has many revealing personal touches: his childhood fear, during a circumcision ceremony, that he would not be as “forthright and strong” as the other boys. His wry imitation of a teacher repeating, “I am a descendant of the famous Duke of Wellington.” His memories of hunting animals on the veld. His passion for his second wife, Winnie Mandela, in hundreds of tender letters written from prison–and his anguished decision to divorce her. There are amusing glimpses of Mandela guided by personal aides, including a maternal Indian woman who advises him on wardrobe (he feels choked when he wears a tie).

“Mandela” delivers a powerful emotional charge in its closing scenes of the Nobel Prize and Mandela’s election victory.

The new South Africa offers the best hope for a new Africa. Its engine might be able to pull the train of corrupt regimes to the north, and lead the way to reform. Mandela’s South Africa seems to be working, despite worrisome crime rates. It is one of the most inspiring stories of our time. But there is more to it than “Mandela” chooses to tell.