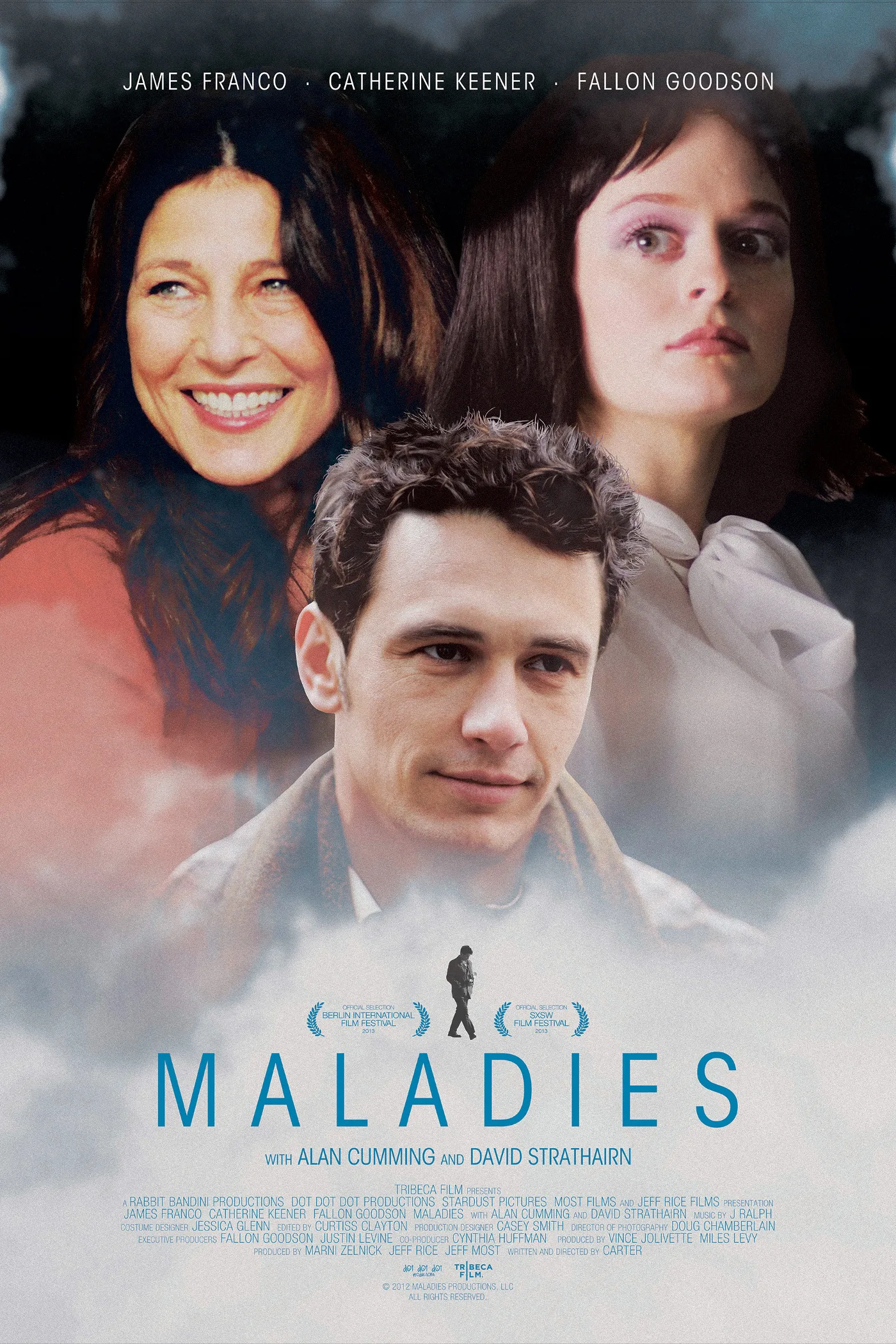

“This is a story about an actor who is no longer acting.” intones the voiceover narrator at the beginning of “Maladies”, the latest collaboration between artist/filmmaker Carter and jack-of-all-trades James Franco, an actor who also could be said to be “no longer acting”, or not entirely. Carter’s debut feature was 2008’s “Erased James Franco”, an experimental presentation with the actor re-enacting scenes from his own films. James Franco’s entire career by now has become an exercise in self-aware commenting-on-itself, and one wonders if the culture has reached its saturation point in that regard. Here, in “Maladies”, he plays a guy named James who was a one-time soap opera actor (a reference to Franco’s own stint on “General Hospital”), and has left the business in order to write a novel. But he can’t seem to get any real work done. Despite some game acting (and one truly superb moment from David Strathairn), “Maladies” remains on too low a boil to communicate any sense of stakes for the various characters. It seems to be trying to say something about creativity, and living one’s life on one’s own terms, but it’s a muddle.

Stylistically, “Maladies” seems to take place in mid-1960s New York, with big cars and women wearing flared skirts and pillbox hats with little nets, but in the first scene, the television shows breaking-news footage of the mass murder/suicide of Jim Jones’ People’s Temple in Guyana, which went down in 1978. The anachronisms feel deliberate, but do not communicate anything specific. Since the film cannot be nailed down to one era, the period clothing feel like costumes, the characters feel like tourists in that world, as opposed to living breathing inhabitants of a certain place and time.

James lives in a big cluttered house in a beachy town on the outskirts of New York with his mentally ill sister, Patricia (Fallon Goodson), and his good friend and artistic ally Catherine (Catherine Keener), who sometimes dresses up as a man, penciling on a lopsided mustache. Catherine is a painter, whose giant complicated mural showing a schooner plowing through stormy seas hangs on the wall in the living room. Patricia is straight out of a Tennessee Williams plays, dancing around to records when she’s by herself, defacing Catherine’s paintings when left alone with them, and floating aimlessly around the house wearing lacy shirts and combing her tangled Louise Brooks wig. James completes the trio.

James is also mentally ill to some undiagnosed degree, but in Franco’s hands it just looks like a combination of quirks. He does not like to be touched. He guzzles down glass after glass of water. He is overwhelmed with confusion by the turn in his own hallway. He turns the radio on and off throughout the night to hear the static. The narrator of the film talks directly to James, as well as narrates what James is feeling. Sometimes James talks back to the narrator, answering its questions. The film is broken up into “chapters” with headings like “Feelings,” “Symmetry,” and we see James, Patricia and Catherine sitting around their house, or going on an outing to a diner, having long rambling conversations about art, and what it means to them. James’ time as a soap opera actor is referenced, on occasion: He left the show, although the rumor is out there that he was fired, and he doesn’t like to talk about it.

“Maladies” seems interested in what it means to be an artist in a brutal world, and what it means to be an outlaw trying to operate in mainstream culture. There’s an awkwardly-paced confrontation in a diner where a fellow customer (Alan Cumming) takes offense at Catherine’s drawn-in mustache and calls her a “Man-lady.” The whole thing feels artificial and imposed. Speaking of Tennessee Williams, who feels like an influence here, Williams gave voice to the misfits of the world, the “sensitives”, as he called them, pointing out the difficult position of the artist, the one who is “different,” and how the world can gang up on such individuals. “Maladies” is too tepid to follow these ideas through to examine their natural implications. With all of the talk about art, it is not clear how James actually feels about his own.

We never learn what James’ novel is about. We never learn why it is he wants to write, or what, even, he wants to say. Other tantalizing questions are left unanswered and unexamined. Why did he leave the soap opera? What were his feelings about being an actor? Why did he give it up? Art itself is seen as an extremely vague and yet somehow important thing to do in your spare time, and it’s not what you make that matters, it’s the desire to make something in the first place. James is amazed that once upon a time there was no such thing on the planet as “Moby Dick”, and then “Poof!” (he exclaims), the next day there was. Catherine gently reminds him that that “Poof” represents years of hard work on the part of the artist. James can’t get interested in that part of it. Art is magical transformation to him, and he wants to be transformed.

Keener is one of cinema’s most watch-able actresses, bringing shades of meaning and a sharp edge to her moments here, suggesting that this cross-dressing woman has come through some sort of fire in her life, and emerged on the other side, not unscathed, but stronger. She treats James with a mixture of baffled affection and mother-hen worrying. Keener does her best with the little she has been given. Franco is impenetrable, giving us a collection of unconnected behavioral tics that do not illuminate the inner condition of the character. What the hell does he want?

It is David Strathairn, as Delmar, the trio’s lonely neighbor, who gives us the film’s strongest moment. Delmar stops by often, to borrow sugar, and do the crossword, but really because he has a doomed crush on James. Delmar was a huge fan of James’ performance on “the soap”, and can’t stop bringing it up, although it bothers James. Delmar treats James with a heartbreaking mixture of helpless desire, fatherly kindness, and old-world politeness. In one scene, when Catherine, Patricia and James crank up the record on the turntable and start dancing around their living room, Delmar stands on the outskirts, looking on. He cannot join in the dance. He is too awkward, too self-conscious. He watches James dance by, and the look of longing on his face, tragic longing that knows it can never reach fulfillment, the loneliness so sharp it brings tears to his eyes, was so poignant and so wrenching that it seemed like it came from another film. A better film, a braver film.