Filmgoers looking for something to explicitly counter August’s summer movie exhaustion should get first in line for “Makala,” a documentary about a Congolese man who makes charcoal, slowly wheels it 30 kilometers to the closest market, and then tries to sell it. The power in this story from comes from its very distilled manner: it tells a timeless story about hard work by completely immersing us in the steps of process, focusing on an act of incredible physical commitment.

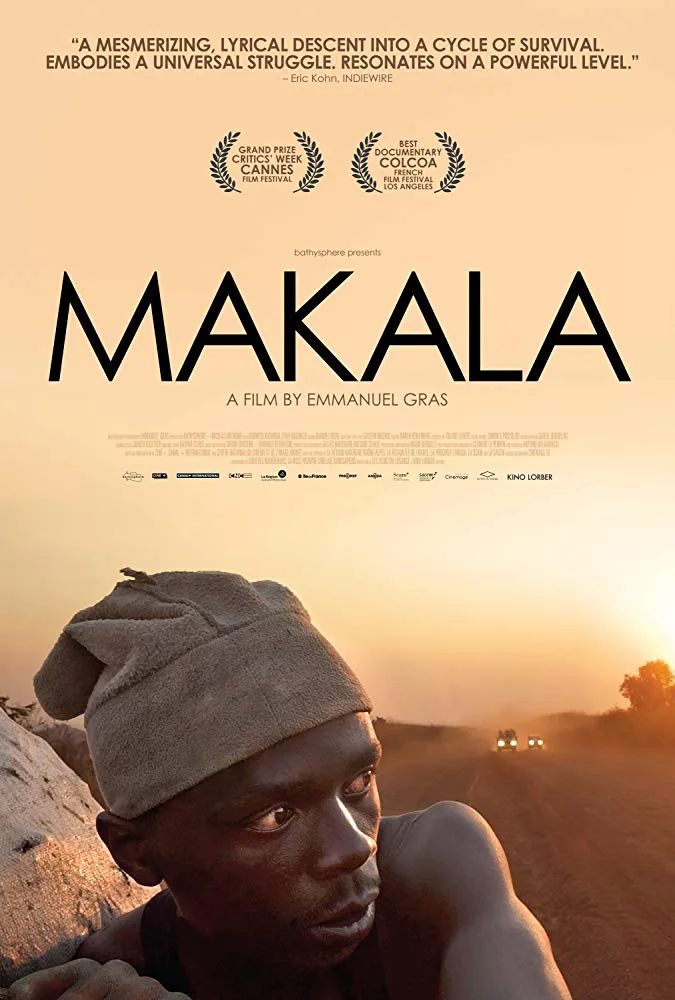

“Makala” starts with a 28-year-old man named Kasongo, the main focus of debut director Emmanuel Gras’ film, walking underneath the natural beauty of a maroon sunrise with an axe over his shoulder. The camera follows behind him, like Mickey Rourke in “The Wrestler,” as he heads to work: chopping down a big tree. We watch him closely as he gets into a rhythm: Thwack. Thwack. Thwack. Eventually, the tree crashes with help from the heavy breezes of the forest. A pile of branches is soon shown. A mud oven is constructed. It’s about 25 minutes into this slow, but extremely rewarding film, in which we learn that this is all to make some charcoal, which he’ll then sell to buy metal slabs to build a house for his wife and kids.

Gras’ solo camera for this endeavor has its own workman-like quality, capturing this procedure more as information first, expression second, while the deliberately paced editing gives us a step-by-step look (the 500-minute cut of “Makala” would reach the same conclusion as this 95-minute one). The movie’s narrative is largely Kasongo’s journey, walking numerous sacks charcoal that have been meticulously strapped to a bicycle that he must balance, but it’s more than enough story for our emotional investment.

This existential tale is truly captivating, like the feeling of getting sucked into Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich as it shares every banal detail of poor Ivan’s life. The potency for stories like these comes from making us process what’s under the microscope; suddenly, the smallest of occurrences are magnified in their importance, and a bare bones objective naturally achieves high stakes.

It’s especially nerve-wracking, for example, when Kasongo approaches a steep incline: nothing exists in the world except him, his bike, and trying to get to the top. In turn, it’s claustrophobic when he does get to the market, and is hit with a tsunami of sound and people. It’s further crushing when everyone is asking for a price lower than his offer.

This is all very powerful, and there’s great poetry within, but let’s not forget that this is a man’s life. So I’m all the more grateful that Gras, with previous experience as a cinematographer, does not make anything overly pretty (only the mournful score could be accused of this). Docs about hardship, as made by outsiders, can sometimes look like art exhibits the subject themselves wouldn’t recognize; Gras’ movie is instead restrained with his compositions, although there’s plenty of gorgeous natural light and empty landscape canvases. In its most effective moments, Gras’ curious camera simply takes a few steps back to see the bigger picture, like Steadicam shots that study the different branches of the cut-down giving tree, or walk around people in a religious service during the film’s final moments, praying for God’s help. “Makala'”s most unforgettable image might involve Duras getting a few steps ahead of Kasongo, but looking back: the camera reveals that he’s not the only one trudging step-by-step with a bike loaded with goods.