Some of you may remember the novel and subsequent film I Don’t Know How She Does It, the title of which was a common expression of wonderment attached to its protagonist, a woman juggling motherhood and career. After a dire, unsettling prologue—one that appears, for a period, to have nothing to do with what comes after—“Madeleine Collins” (a title that, like the aforementioned prologue, only makes sense late in the movie) shows us how one woman juggles a career and two different households in which she’s a mother.

There’s Geneva, where “Margot” is the hard-pressed partner of Abdel and mom to adorable clingy toddler Ninon; she works in the city as a translator. Then there’s Paris, where “Judith” is the adored and sharp-dressing wife of Melvil, a celebrated orchestra conductor. There she looks after two sons; one of them, Joris, is getting old enough to suspect that his mom is not entirely what she seems.

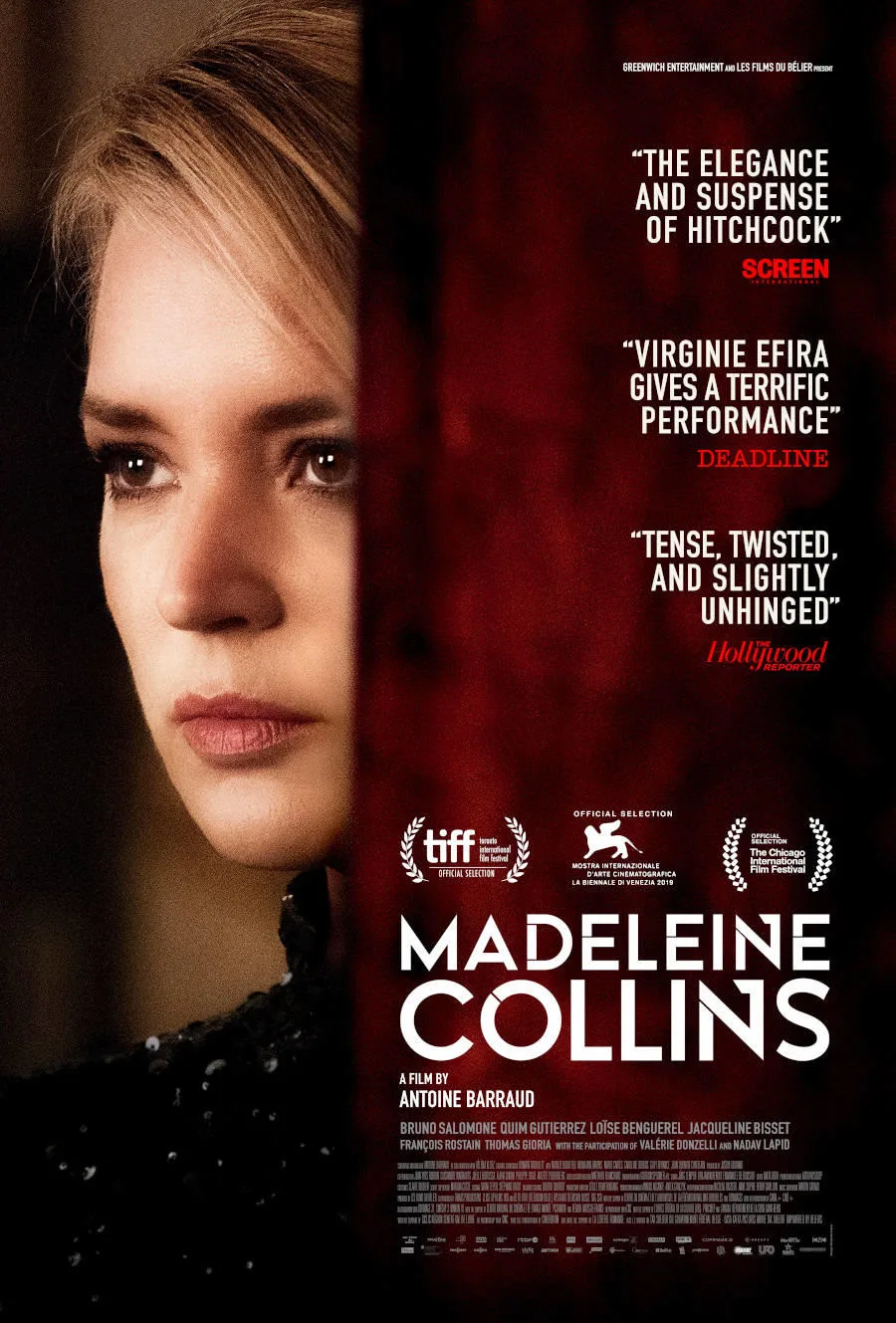

Margot and Judith are the same woman, played with an intense emphasis on the stress that’s building in her untenable situation by Virginie Efira, best known to viewers here for her work in Paul Verhoeven’s “Elle” and “Benedetta.” In Antoine Berraud’s film, which he wrote in collaboration with Hélène Klotz, she begins on a note of everyday beleaguered confidence and/or faith that’s not uncommon in a woman’s world. The more we learn about her situation, the more curious it becomes. Abdel is aware of her other life in Paris. And Melvil knows who Abdel is. More than the audience does at first, actually. But Melvil is not privy to the life his wife shares with the other man. It turns out that Judith/Margot’s parents have ties to both domestic situations but no idea of the whole picture.

As snags and coincidental meetings mount up—here’s a former co-worker from years back encountering her under a different name in Geneva! Here’s the scruffy underworld ID forger who has a crush on her and so deliberately gave her a card that expired way before five years were up!—and Judith comes more and more under the snooty eye of Parisian teen son Joris (played with note-perfect petulance by Thomas Gioria), this character, whose true name is never, it seems, really known to the viewer, starts to come apart.

Berraud’s juggling a few themes here—that of the varied roles we’re compelled to take on in life, here pushed to hard limits, and that of the difficulty of being a woman, a popular topic these days. Between the prologue and how the movie’s narrative grows more frantic—not to mention the use of Romain Trouillet’s music that owes a lot to Hitchcock-era Bernard Herrmann—Berraud wants to push this material into the realm of something like a suspense thriller. It doesn’t quite work, especially given the reveal of what drove Efira’s character to her deceits, which, while meant to be heartstring-pulling, plays as rather more banal than one might have expected.

But the settings are better than credible, as is the acting across the board. Quim Gutierrez is sympathetic and surly as Abdel, who eventually grows so exasperated with his arrangement that he brings another woman into the household. Bruno Salomone, as Melvil, projects a relatively benign self-involvement that makes his inability to see what’s going on almost a given. Jacqueline Bisset is welcome in a supporting role as Margot/Judith’s mother. But the movie is most naturally a showcase for Efira, whose work as an unusual 17th-century nun in “Benedetta” demonstrated she could play dazzling and tormented with equal facility and who gets to work a similar range here.

Now playing in theaters.