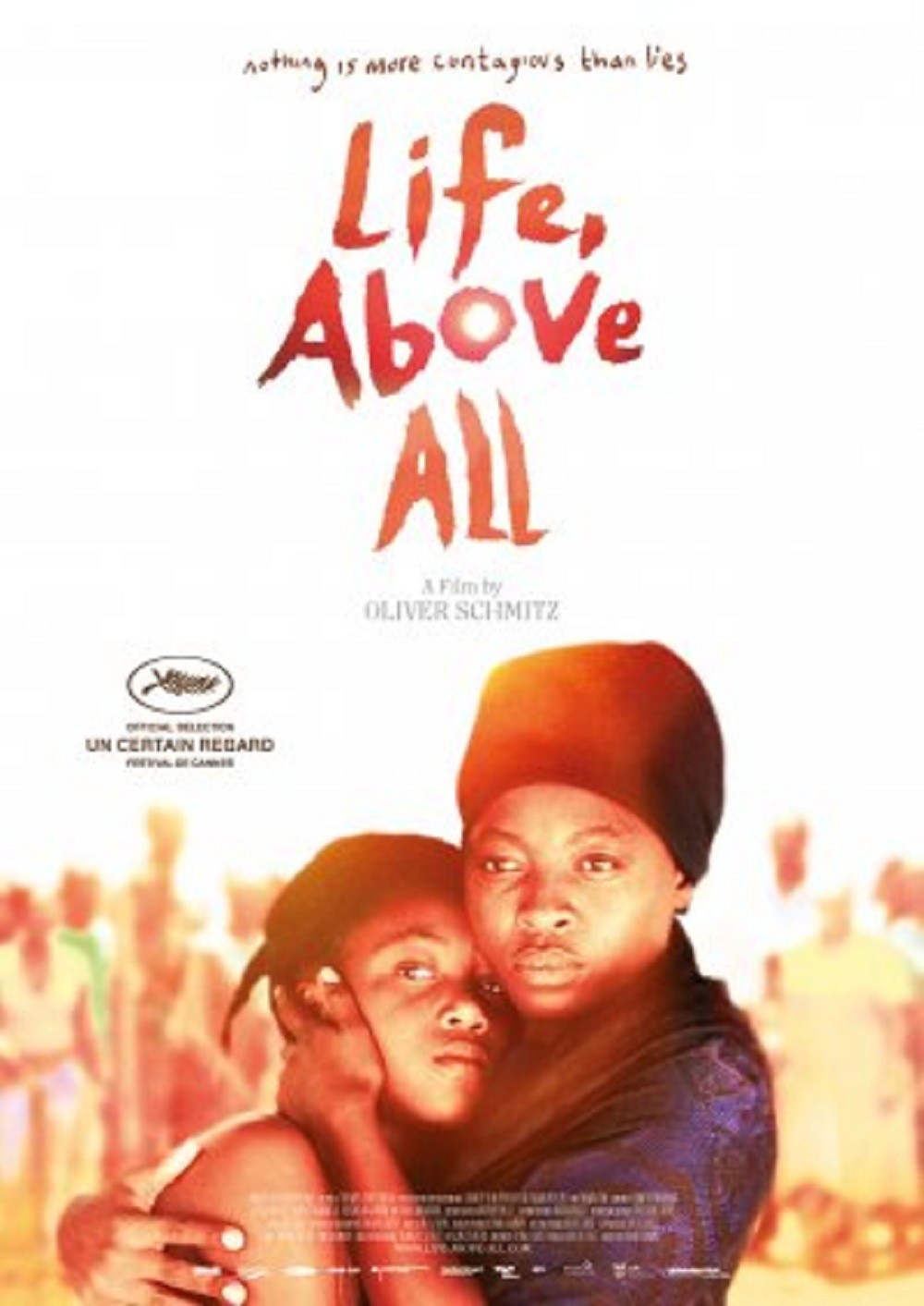

Oliver Schmitz‘s “Life, Above All” earns the tears it inspires. The film is about deep human emotions, evoked with sympathy and love. It takes place entirely within a South African township near Johannesburg, one with modest prosperity and well-tended homes. It centers on the 12-year-old Chanda, who takes on the responsibility of holding her family together after her baby sister dies.

As the film opens, Chanda (Khomotso Manyaka) visits an undertaker to examine the inexpensive coffins on display. This is a task no 12-year-old should ever have to endure. But her mother, Lillian (Lerato Mvelase), is immobilized by grief and illness and her father by drink. The next-door neighbor, Mrs. Tafa (Harriet Manamela), helps her care for two younger siblings.

Suspicion spreads in the neighborhood that the real cause of the family’s problems is AIDS, although the word itself isn’t said aloud until well into the film. Its absence forms a fearful echo chamber — reflecting South Africans’ own insistence, until recent years, of denying the reality of AIDS. A family linked to the disease by rumor or gossip is ostracized, which is why Mrs. Tafa facilitates Lillian’s “visit” to distant relatives.

Chanda does what she can to care for her siblings, attend school and keep up appearances. Her own good heart is demonstrated by her friendship with a schoolmate named Esther (Keaobaka Makanyane), who is forced into prostitution to earn the funds for survival. It goes unspoken between them that this could lead to AIDS for Esther herself. The South African tragedy was that former president Thabo Mbeki persisted in puzzling denial about the causes and treatment of AIDS, so many who suffered and died of AIDS need not have. This contributed to a climate of ignorance and mystery surrounding the disease, which only increased its spread.

By directly dealing with the poisonous climate of rumor and gossip, the film takes a stand. But in nations where AIDS has been demystified, “Life, Above All” will play strongly as pure human drama, and of two women, one promptly and one belatedly, rising courageously to a challenge.

The performances by the two young girls are remarkable here. They have seen and internalized unspeakable experiences. Their faces are young, but their eyes are wise. Whenever I see such early performances by inexperienced actors, I wonder where they come from. No doubt director Oliver Schmitz had much to do with these portrayals. The casting process must have been crucial. But Manyaka and Makanyane have grave self-possession; they never even slightly overact. I met Khomotso Manyaka at Ebertfest 2011 and found her a cheerful, friendly teenager. Where did she find these resources? Where does any actor?

As for Harriet Manamela as Mrs. Tafa, she has a central role. This township is far from the poorest in South Africa. In the terms of that neighborhood, many households are middle class; Mrs. Tafa embodies authority. She is fiercely proud of her son, a star athlete. She shares the general taboos about AIDS, but she is a good person, kind, with sympathy that she sometimes keeps concealed.

There is a scene where fearful neighbors gather outside Chanda’s house, inflamed by their suspicions about her mother. Mrs. Tafa confronts them, surprising even herself, perhaps, by how she rises to the occasion. Schmitz’s camera placements here are confident and underline the drama.

The film’s ending is improbably upbeat: Magic realism, in a sense. It works as a deliverance. Dennis Foon’s screenplay is based on the novel Chanda’s Secrets by Canadian writer Allan Stratton. It is a parable with Biblical undertones, recalling Cry, the Beloved Country.