Claude Chabrol’s “Les Biches” depends almost entirely on style, and as style it succeeds. He is not so much interested in his story as in how to tell it. He favors muted colors, mostly pastels, and many of his scenes are shot in the light of late afternoon.

His characters fit these colors and moods; they seem in a trance sometimes, moving slowly, speaking absently. And his camera movement is meticulously planned. We notice scenes where the camera and the actors move together in a sort of minuet. Three or four shots, using steps we don’t see or mirrors we don’t expect, have the grace of dance.

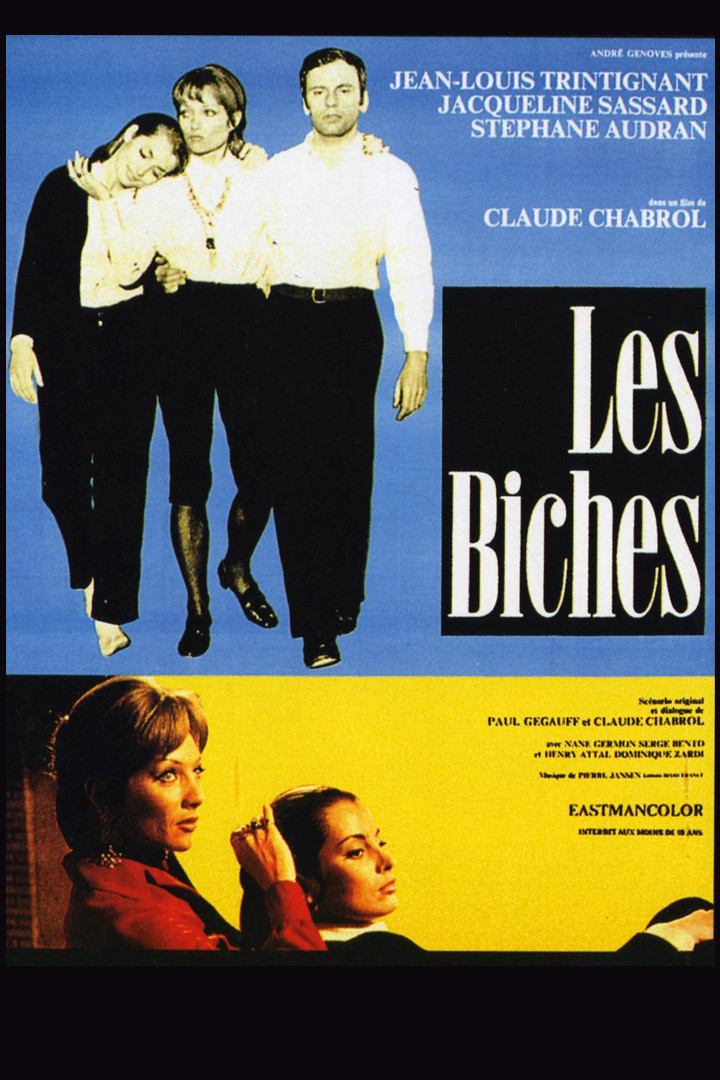

Chabrol is often considered the father of the French New Wave. He is known over here for “Les Cousins” (1959), “Les Bonnes Femmes” (1960) and last year’s “The Champagne Murders.” Unlike his colleagues in the New Wave (Godard, Truffaut, Resnais) he has steered away from politics and into a very smooth, almost ethereal directing style. “Les Biches,” a success at the 1968 New York Film Festival, ranks with his best work.

Usually we have to wait a year or two in Chicago to see the best new foreign films. But “Les Biches” opened here at the same time as its national release, and it’s not hard to figure why. It’s being promoted along rather hard lines as one of those lesbian sex flicks. The Loop Theater, with remarkable bad taste, advertises on the marquee: “Boldest Fem Film of ’69.” And the people ahead of me in line thought the title was “Les Bitches.”

This sort of promotion isn’t surprising; foreign films have had to win bookings for years on the basis of their usually exaggerated erotic qualities. But let it be said that “Les Biches” is in no sense an exploitation film, is not particularly erotic and achieves its purpose mostly, by seducing us into the mood of the characters.

They are strange, self-obsessed people. The young girl (Jacqueline Sassard) is first seen on a Paris bridge, drawing on the pavement. We discover nothing about her past; all we know is that she’s a waif, poor and apparently alone. The older woman (Chabrol’s wife Stephane Audran, who won the best actress award at Berlin) conceals a consuming selfishness beneath a mask of sophistication. The man (Jean-Louis Trintignant) hardly figures at all. We are told he’s an architect, but we learn little more; he drifts along, first attracted to the girl and then ruthlessly possessed by the women.

The characters live in a vacuum, moving back and forth between Paris and the woman’s seaside home (inhabited by a comic set of servants). The characters move gracefully, say little of substance, spend most of their time at leisure.

The camera keeps moving, but the action seems to slow down and almost stop. The young girl is in a strange position; she loves both the woman and the man, and is happy that they love each other. But she is afraid of being shut out. She has come out of nothing and is afraid to go back. So gradually a great jealousy grows in her (underlined by the eerie music of Pierre Jansen). And then the film is over.

It is not the sort of film a lot of moviegoers find satisfying; certainly not the skin-flick fans. But in its highly mannered way, it goes against the flashy camera tricks and fashionable gimmicks of 1960s directors, and probes for the subterranean psychological passions of, a Henry James novel. And in that way “Les Biches” becomes a moody, quiet, highly personal expression.