A movie should present its characters with a problem and then watch them solve it, not without difficulty. So says an old and reliable screenplay formula. Countless movies have been made about a boy and a girl who have a problem (they haven’t slept with each other) and after difficulties (family, war, economic, health, rival lover, stupid misunderstanding) they solve it by sleeping with each other. Now we have a movie about two homosexuals that follows the same reliable convention.

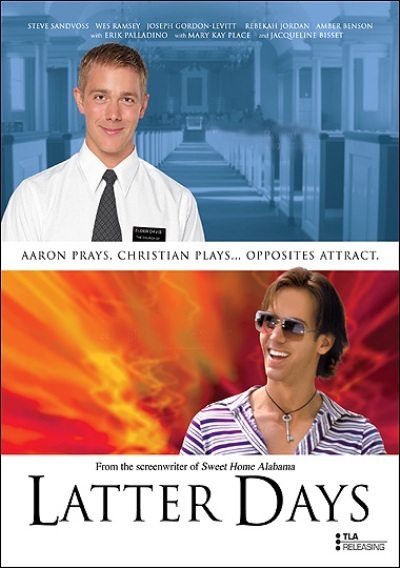

Although much will be made of the fact that one of the characters in “Latter Days” is a Mormon missionary and the other is a gay poster boy, those are simply titillating details. Consider the sub-genre of pornography in which nuns get involved in sex. We know they’re not really nuns, but the costuming is supposed to add a little spice. By the same token, Davis (Steve Sandvoss) is a Mormon only because that makes his journey from hetero- to homosexual more fraught and daring. He could have been a Presbyterian or an atheist vegan and the underlying story would have been the same: A character who considers himself straight is seduced by an attractive gay man and discovers he has been homosexual all along.

Since it is obvious to us from the opening shots that these two characters are destined for each other, the plot functions primarily to add melodrama to the inevitable. And there’s change in both men. Christian (Wes Ramsey), who at the beginning is a shameless slut, bets a friend $50 he can seduce his new neighbor, but by the end of the film he truly loves him and has been so transformed by this experience that he volunteers for an AIDS charity and in general is transformed into a nice guy. It’s as if the Mormon missionary achieved his goal and converted him, in slightly different terms than he expected.

The $50 bet is a cliche as old as the movies, and of course it always results in the bettor really falling in love, while the quarry finds out about the bet and is crushed. One of the sly pleasures of “Latter Days” is the sight of this gay-themed movie recycling so many conventions from straight romantic cinema, as if it’s time to catch up.

The film is made with a certain conviction, and the actors deliver more than their roles require; there are times when they seem about to veer off into true and accurate drama (as when Christian encounters a bitter, dying man), but by the end, when Davis is back in Pocatello, Idaho, and his homophobic mother (Mary Kay Place) is sending him for shock treatment, we realize the movie could have been (a) a gay love story, or (b) an attack on the Mormon Church, but is an awkward fit by trying to be (c) both at the same time.

I also question the character of one of Davis’ fellow missionaries, who is outspokenly anti-gay in a particularly ugly way. Is this character modeled on life, or is he a version of the moustache-twirling villain? And then there’s Christian’s best friend, Julie (Rebekah Jordan), who of course is a hip and sympathetic African-American woman. You get to the point where you realize everyone in this movie has been ordered off the shelf from the Stock Characters Store, and none of them wandered in from real life.

Is there a way in which the movie works? Yes, it works by delivering on its formula. We sense immediately that Davis and Christian are destined to be lovers, and so we watch patiently as the screenplay fabricates obstacles to their destiny. We identify to some degree with them because — well, because we always tend to identify with likable characters in love stories. Maybe the fact that they’re gay will help some homophobic audience members to understand homosexuality a little better, although whether they will attend the movie in the first place is a good question.

What I’m waiting for is a movie in which the characters are gay and that’s a given, and they get on with a story involving their lives. Or maybe for a satire in which two heterosexuals move in next to each other and battle their inner natures until finally love tears down the barriers and they kiss, even though one is a boy and the other a girl. That obviously would be silly, and the day will come when a movie like this seems silly, too.