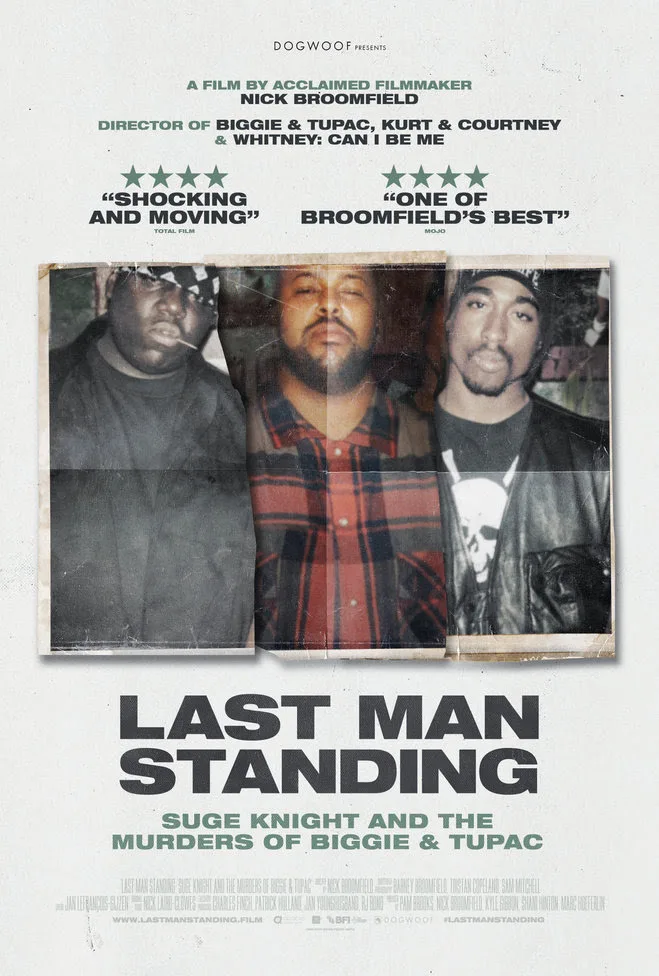

Someone along the way during the production of “Last Man Standing,” must have looked at Nick Broomfield and said, “You again?” The director has long been one of the most vocal filmmakers about the lives and deaths of Christopher Wallace and Tupac Shakur, really kickstarting entire Reddit threads of conspiracy theories with his 2002 offering “Biggie and Tupac,” a film that captures not only the life and legacy of two of the most important rappers of all time but asks some interesting questions about their murders. Why return to this subject two decades later? It almost feels like there’s no return here, because Broomfield never left it behind.

He’s clearly obsessed with this story and his theories about what happened, and that obsession has sent him down a rabbit hole of anecdotes that have clouded his filmmaking skills like never before. “Last Man Standing” is a startlingly scattershot piece of filmmaking from a director who normally has a sure, personal hand on his projects. To say he can’t find a throughline here would be an understatement as he jumps around the ‘90s rap scene, revisits lives that have been thoroughly documented by now, and then bounces a few theories off the wall again, just to make sure you haven’t forgotten them. It’s clear Broomfield hasn’t put any of this behind him, and his personal investment in the stories of Wallace, Shakur, and, really, Russell Poole have derailed his ability to form all of his emotions and thoughts into a coherent, valuable film.

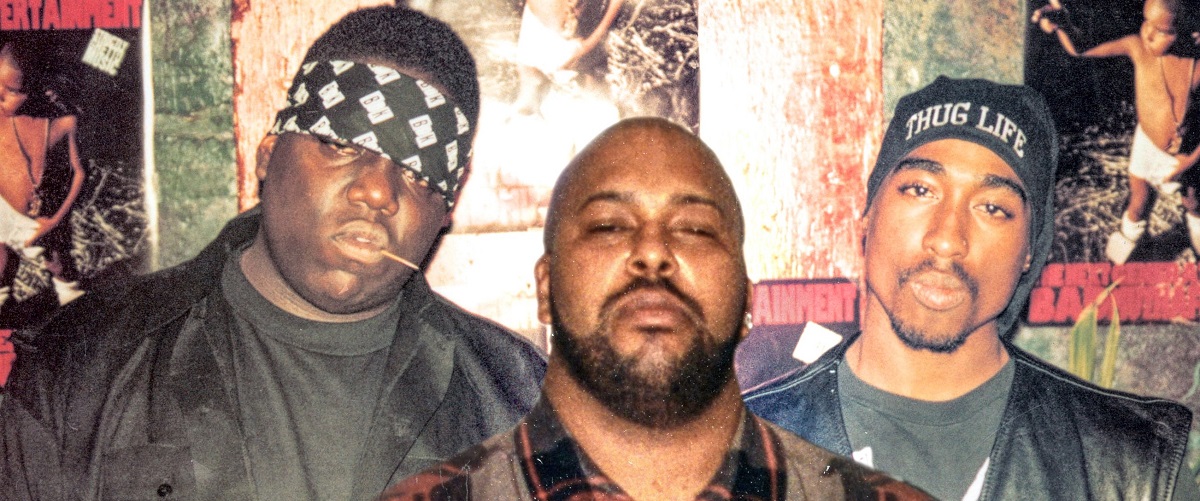

Most of “Last Man Standing” consists of interviews with people who were caught in the powerful web of Marion “Suge” Knight, head of Death Row Records in the ‘90s. Rather than start with the biographies of Tupac and Biggie—Broomfield at least understands those are probably well known by now—he expends a lot of energy on what it was like to be in the world of Knight in the ‘90s, when Tupac was becoming a household name. Gang affiliations, outbursts of violence, highly sexualized roles for women—“Last Man Standing” paints a portrait of street culture exploding into boardrooms and recording studios. He does so through a series of interviews with people who were reportedly there. So, a stunning amount of “Last Man Standing” consists of hearing stories about Knight’s propensity for violence or how Tupac changed after doing time. We know all of this. It’s almost like Broomfield set out to find the people at the company who had never done an exit interview, and never asked himself if they had something new to say.

Even more problematic, Broomfield can’t maintain focus. He inserts himself into scenes and interviews, which isn’t new for him, but it creates a sense here of a filmmaker trying to shape the film while he’s making it. To say that “Last Man Standing” lacks focus would be an understatement. He’s constantly jumping around from gang culture to musical impact to personal connections to theories about the deaths of Shakur and Biggie, even incorporating some interviews from “Last Man Standing” to reemphasize his points. This would be one thing if the bulk of “Last Man Standing” felt like it enhanced that old footage or cast it in a new light. It does not.

“Last Man Standing” doesn’t so much reframe an old story as rehash it from a few new points of view. Broomfield seems to have lost the thread regarding what makes this story interesting—two blindingly talented men brought down by violence, which may have been covered up by the Powers That Be. Stories from people we’ve never seen before about how dangerous it was to be in Knight’s world? It adds nothing to the overall fabric that we didn’t already know or that isn’t really verifiable (a whole lot of “Last Man Standing” could be politely called hearsay in its “I knew a guy who saw a guy…” tone).

Part of the problem could be that it feels like Broomfield had an opportunity to truly update his obsession. We know more about police corruption now than we did in the ‘90s or when he released his first film in 2002. And stories of gang violence and institutional racism have different weight. So why avoid greater context to this story? Why make a film that feels like a continuation instead of one that asks how the industries of both rap and police work have changed since Biggie and Tupac? No one asked “why” in this production.

Maybe I’ve just seen too many documentaries about Christopher Wallace and Tupac Shakur, but I feel like that’s true of everyone who might be interested in what is basically a sequel to “Biggie & Tupac.” As fascinated as I am by these men and the stories around their murders, I was consistently and increasingly frustrated by “Last Man Standing,” a film that reminded me that not every interview about incredible people is inherently incredible in its own right.