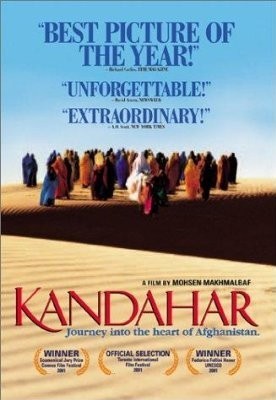

When she was a child, Nafas was taken to Canada, while her sister stayed behind in Afghanistan. Now Nafas has received a letter from her sister, who lost both legs after stepping on a land mine, and plans to kill herself during the final eclipse of the 20th century. Nafas sets off on a desperate journey to smuggle herself from Iran into Afghanistan, to persuade her sister to live. “Kandahar” follows that journey in a way that sheds an unforgiving light on the last days of the Taliban.

I saw the movie, by Iran’s Mohsen Makhmalbaf, at Cannes 2001, where it was admired but seemed to have slim chances of a North American release. Of course 9/11 changed that, and Kandahar became a familiar place name. The movie is especially accessible because most of it is in English–the language of the heroine, who keeps a record of her journey on a tape recorder, and also the language of one of the other major characters.

Nafas (Nelofer Pazira) is unable to get into Afghanistan by conventional means, perhaps because her family fled for political reasons. In Iran, she pays an itinerant trader, who travels between the two countries, to bring her in as one of his wives; she wears a burqua, which covers her from head to toe, making the deception more possible. And as she sets out, we begin to realize that the journey, not the sister’s fate, is the point of the film: Nafas is traveling back into the world where she was born.

Makhmalbaf and his cinematographer, Ebraham Ghafouri, show this desert land as beautiful but remote and forbidding. Roads are tracks from one flat horizon to another. Nafas bounces along in the back of a truck with other women, the burqua amputating her personality. There are roadblocks, close calls, confusions, and eventually the merchant turns back, leaving her in the company of a boy of 10 or 12 named Khak (Sadou Teymouri). With that terrible wisdom which children gain in times of trouble, he knows his way around the dangers, and takes $50 to lead her to Kandahar. At one point they trek through a wilderness of sand dunes, and when he finds a ring on the finger of a skeleton he wants to sell it to her.

Nafas grows ill, and Khak takes her to a doctor. She stands on one side of a blanket, the doctor on the other, and he talks to her through a hole in the fabric. The Taliban forbids any more intimate contact between unmarried men and women; he can ask her to say “ah,” and that’s about it. But this doctor (Hassan Tantai) has a secret–a secret he reveals when he hears her English with its North American accent. Khak hangs around, hungry for any information he can sell, until the doctor bribes him with peanuts and sends him away.

“Kandahar” does not provide deeply drawn characters, memorable dialogue or an exciting climax. Its traffic is in images. Who will ever forget the scene of a Red Cross helicopter flying over a refugee camp and dropping artificial legs by parachute, as one-legged men hobble on their crutches to try to catch them? The movie makes us wonder how any belief system could convince itself it was right to make so many people miserable, to deny the simple human pleasures of life. And yet the last century has been the record of such denial.

Khak, the boy, has been expelled from school. We see one of the Taliban schools. All of the students are boys, of course–women are not permitted to study. That may be no great loss. The boys rock back and forth while chanting the Koran. Not studying or discussing it, simply repeating it. Then they are drilled on the parts of a rifle. “Weapons are the only modern thing in Afghanistan,” the doctor tells Nafas.

“Close-Up,” a 1990 film by the Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami about an impostor who pretends to be Makhmalbaf, has just been released on DVD by Facets. Makhmalbaf stars as himself.