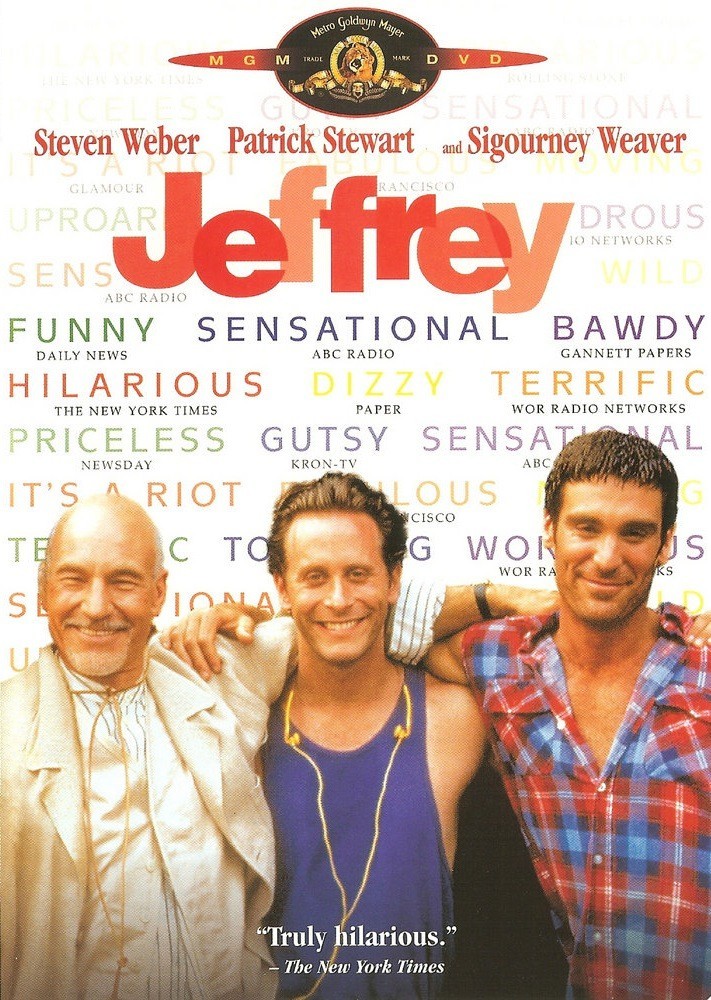

“I love sex. It’s just one of the truly great ideas,” the hero of “Jeffrey” tells us in the film’s opening moments. And for a gay man like Jeffrey, there was the brief moment of sexual liberation to enjoy, before the specter of AIDS closed down the party. Now Jeffrey (Steven Weber) finds his sex life so frightening that he decides to swear off – to become celibate, and find other interests. It’s not so much that he fears becoming HIV-positive himself, although he does; it’s that he fears falling in love with someone who will die.

Well, everybody dies sooner or later, but Jeffrey is protective and can’t see setting himself up for a loss.

That’s why it’s inconvenient one day when he’s working out at the gym, and Steve (Michael T. Weiss) makes a pass, and the earth shakes. He’s powerfully attracted to Steve, but fights to suppress his feelings.

Jeffrey’s dilemma was the subject of an Off-Broadway play by Paul Rudnick (a.k.a. Libby Gelman-Waxner, the chatty film columnist for Premiere magazine). Now it’s been adapted for the screen, again with revue devices, like speeches directly to the audience, cameo comedy roles and even a walk-on for Mother Teresa.

Seeing the saintly Mother, another of Jeffrey’s friends makes a snap judgment: “She’s had work.” The line comes from the movie’s most sharply drawn and entertaining character, Sterling (Patrick Stewart, of “Star Trek: The Next Generation”), whose lover, Darius (Bryan Batt) is a dancer who is HIV-positive. Sterling is a meticulously maintained middle-age man with a barbed tongue, quick intelligence and the belief that love is so rare that when it comes, you have to accept it on its own terms, even if that means (as it does in Darius’ case) that HIV comes along with it.

Jeffrey can’t see it that way, and goes through a series of rather unconvincing denials of love before finally caving in to Steve’s charm and technique. And that’s basically what the movie is about – love, risk and loss – apart from the vignettes, which include Sigourney Weaver as a TV-style self-help guru, and Olympia Dukakis as the mom of a man who intends to become not merely a woman but a lesbian.

“Jeffrey” is not without its moments, but the movie never really convinced me it knew what it was doing. It’s more a series of sketches and momentary inspirations than a story that grows interesting – and to guard against our growing too involved, there are intertitles and other self-conscious devices, including a sequence where after two men kiss on the screen, the film cuts to two teenage couples in an imaginary movie audience who find the kiss hard to deal with. This sequence contains the idea for an interesting short film, but as a scene in this one, it’s all wrong.

Another melancholy problem is illustrated by the movie itself. Although “death” has long been a code word in poetry for the moment of climax, the linking of sex and death by AIDS has made it difficult to tell gay male love stories that don’t have at least the possibility of a macabre subtext. One solution is to deal with the situation in true drama, as “Longtime Companion” and “Philadelphia” did. Another may be to set the story back to the years before AIDS.

What “Jeffrey” does is confront the problem through humor and self-analysis, which is interesting. But when there’s a problem love story, and the problem is of more concern to the characters than the love, you’ve got . . . well, you’ve got a problem.