We get a lot of movies about noise these days: gunshots, screams, explosions, fist thunks, thunderous roars, revving engines, squealing tires and those deafening sonic swooshes that accompany nearly every corporate logo before the feature even gets started. But we don’t experience many moments of silence at the movies (and I’m not just talking about the audiences). “Into Great Silence,” though devoid of narration, musical score or much at all in the way of dialogue, encourages us to listen closely: to the sound of snow falling in the mountains, a nocturnal prayer whispered in a small wooden cell with a knocking tin stove, a bell rope pulled in a chapel. Nobody yells. Nothing detonates.

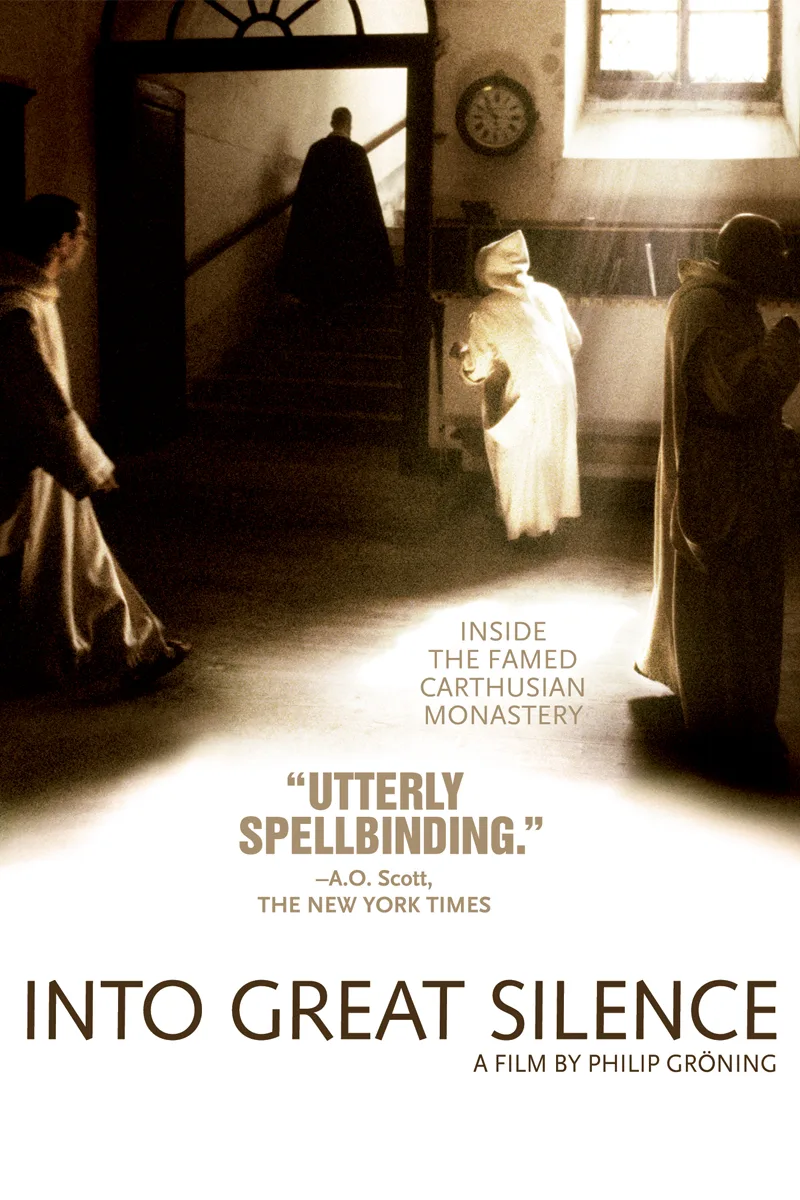

The images also open up to us gradually and quietly. We’re not bombarded with fusillades of shots: “Look at this! Now this! Now this!” “Into Great Silence” unfolds with its own gentle, unforced rhythms, designed, as German filmmaker Philip Groning has said, to be less a “documentary” than a meditation.

Groning spent six months living with the monks of the eremitical Carthusian order at the Grand Chartreuse Charterhouse, or monastery, in the French Alps. He brought with him only a camera and basic sound equipment — no crew, no lights — to capture the daily lives, prayers and routines of this most ascetic of Catholic orders, which was founded by St. Bruno in 1084. The monks, who have taken a vow of poverty, subsist on very little. They pray aloud at times and sing solemn Gregorian chants, but they rarely speak, except on their Monday walks. If cinema had existed more than a thousand years ago, this is quite like what it may have recorded.

I must confess my fondness for contemplative movies of this sort. The less frenetic onscreen activity you are forced to endure, the more you’re able to notice. And the form of “Into Great Silence” is ideally suited to its subject. The monks lead a regimented existence (you can see a typical weekday schedule, and learn about their history, at their official Web site, www.chartreux.org), but time is allotted for the introspection and reflection that are essential to their devotion. You’re given the opportunity to contemplate details, including ones you may overlook in the rush and routine of your own everyday life.

The film is structured, appropriately, with attention to the ritualistic and cyclical nature of these lives — and, perhaps to a less rigorous extent, all of our lives: work, meals, chores, time alone (with God), time with others. And then there are the rhythms dictated by the passage of time: the daily progression of darkness into light and back again; the passage of the seasons; the aging of the monks’ own bodies. Intertitles with biblical quotations are repeated like chants, sometimes followed by three close-ups of monks looking into the camera. There’s so much to watch and listen to.

In one of the few segments where anyone speaks, a monk says, “In God there is no past. There is only the present.” Oddly, or not, watching this movie I was reminded of the final part of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” where Keir Dullea silently grows old in a mysteriously sterile 18th century habitat. One day, while eating, he knocks over a glass, and it shatters on the floor. In the next moment, he is much older. How much time has passed in the interim? The monks’ (and the film’s) conception of time is similarly static. Groning approached the Carthusians for permission to shoot the film in 1984, and they said they weren’t quite ready. Sixteen years later, they said they were.

So, what happens in the course of the picture? As you would expect, everything and nothing. You get the feeling that whatever you witness has probably happened countless times before. Novices are admitted. A clock is re-set, then straightened. On one sunny walk, there’s a discussion about the moral implications of hand-washing: how it should be done, and how much. On another walk, the monks slide down a snowy slope. Those are among the action-packed highlights.

But they are not what “Into Great Silence” is about. A movie is always about what happens to you as you watch it, and Groning’s stated intention was to entice the viewer to assemble his or her own experience of the film by asking questions and making discoveries as it unreels. Sometimes these questions are elemental: What am I looking at? Is it day or night? At other moments they are experiential: What task or ritual is this? Where are they going? And at others they are more existential: What does it take to find meaning in the physical and psychological discipline of such a life? Are the monks happy, or content? What does the concept of “happiness” mean in this context?

Each of us is left to discover the answers for ourselves.