“In Transit” is a film about people riding a train from one place to another, talking about their lives with other passengers. That’s all there is to it, and yet that’s not all there is to it. The movie is a throwback to an earlier era of documentaries, when filmmakers did not feel obligated by commercial pressure to give their film the shape of a thriller, a sports film, a mystery or anything else, but instead simply brought their cameras into people’s lives. The setting is the Empire Builder, an Amtrak train that journeys between Chicago and the Pacific Northwest, serving Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon as well as points in between; its route includes North Dakota, a new oil boom region that supplies many of this film’s intriguing characters.

This film is nearly as welcome a breath of fresh air as my favorite film of 2016, Kirsten Johnson’s “Cameraperson,” an autobiographical essay film made up of footage shot by a camerawoman over three decades, arranged in editing so that fragments of other people’s lives explore universal concerns, such as war, trauma, childhood, parenting, illness, death, and the ethics of storytelling. “In Transit” is similarly supple and mysterious in the stories it tells and the points that it makes. And when it does make points, it never hammers them. It has a light touch, and many of the larger connections it draws are conveyed through editing, as when characters talk about the past that they left behind when starting over, and the movie cuts to a shot from the last car on the train, watching the rails recede into the distance.

Considering that “in Transit” has no main character—unless you count the train itself—it is a remarkably coherent work. Clocking in at a brisk 75 minutes, it gives us tantalizing glimpses into people’s lives that suggest the totality of their experience while leaving us wanting more. This is my principal complaint about the movie—it’s a rare feature that might’ve benefited from a longer running time, because some of the characters’ stories are interesting enough to linger on; at the very least, there are points where I wouldn’t have minded if the filmmakers had stayed with one person for a couple minutes longer instead of cross-cutting between two or three stories.

But the impulse to keep things moving relentlessly forward suits a film set on a train, and the people we do meet are consistently fascinating, even when we initially mistake them for merely eccentric or self-involved. We meet a mother and a daughter who bond by riding the rails, an immigrant woman who wants to see as much of her new country as possible, and a young man who’s nervous about meeting a woman he courted from afar for many years. A very pregnant woman has a long conversation with an older man who keeps taking pictures through the windows, documenting his trip; we don’t learn his story until much later, and it’s so moving that I’d rather not spoil it here.

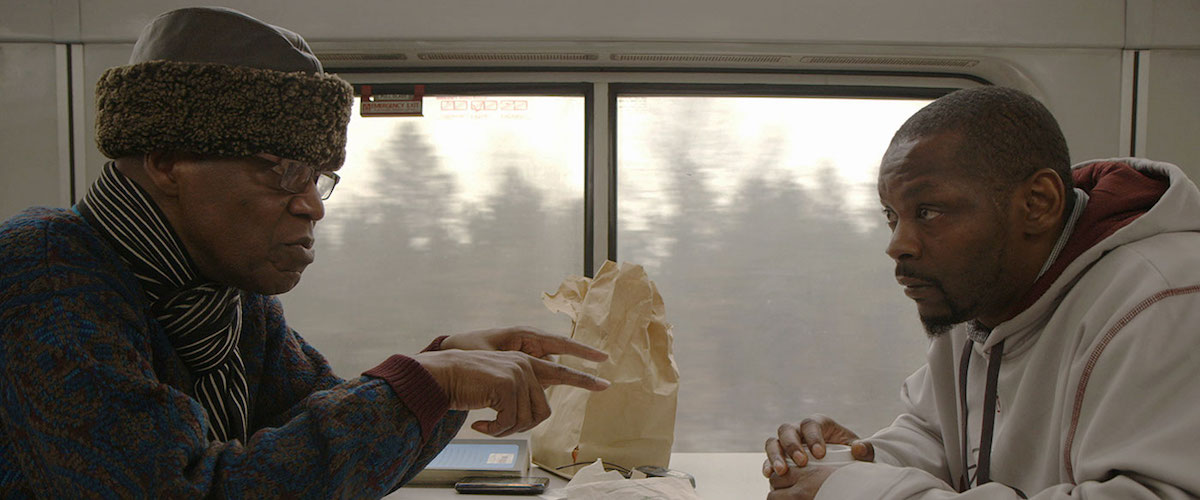

“In Transit” is also a rare American film that gives us a sense of the richness of this country, both geographically and in terms of life experience. While the passenger manifest is predominantly white—unsurprisingly, considering the states that the train is passing through—there are passengers of many other races and ethnicities, as well as a variety of social classes, including many working class people who are either coming from oil fields or headed there. A series of scenes in the film’s midsection lets us eavesdrop on a thirtysomething African-American man as he’s counseled by a much older African-American man who knew Dr. Martin Luther King; their conversation focuses on optimism, ethics and the importance of love; its conclusion, a solo statement about life by the elder man, is one of the highlights of this moviegoing year.

As anybody who’s familiar with public transit will attest, there’s something about taking a long ride by yourself that encourages you to volunteer information you might not discuss with your own family. Passengers talk to the filmmakers and to each other about their relationship and marital troubles, their doubts about their career, their fear of aging, illness and death, and the difficulty of making a living in a supposed land of plenty.

As the characters talk, mill about, eat, sleep, play cards and talk on the phone, the film crew’s cameras frame them within an array of geometric spaces created by the rectangular shapes of windows and door frames, and track their progress from car to car, the overhead lighting panels and regimented rows of seats stretching into the distance in exaggerated perspective that makes the train seem a thousand miles long. The sound design is exceptional as well. There is no score to speak of, only snippets of pop songs that we hear briefly on passengers’ phones, plus a bit of an old standard played (with merciful brevity) on a ukulele. After a while, the noises of the train itself become the binding element of the experience of watching “In Transit”: the bell going ding-ding as the train goes into a station, the horn blowing as the train glides around corners or passes through towns.

No surprise that such an old-school project was masterminded by the late Albert Maysles (1926-2015). With his brother David (1931-1987), Maysles helped create “Direct Cinema,” an observational type of filmmaking that believed that the filmmaker should be as unobtrusive as possible, both in the room with subjects and later on when the footage is being edited. Maysles talked about “In Transit” for nearly two decades before this movie finally, posthumously appeared. It was originally envisioned as his pet project made of footage collected while riding trains: he would just take out his camera, interview people who were in the compartment with him, and then either keep going after they got off the train or disembark with them and see where they were going. I’m not sure how much footage he collected, but I’m told by people who worked with him that there was a lot. When I interviewed him for the Star-Ledger in 2000, he talked about and described some footage he’d already shot and made “In Transit” sound like the movie he’d been building up to throughout his long career.

This film is something else, though —a collaboration between Maysles and co-directors Nelson Walker and Lynn True (who edited, brilliantly). None of the stuff Maysles shot over the years is in this movie: it’s a one-shot project that attempts to realize his plan within a contained space and time span. The footage was shot by a team of camerapersons roaming about the train, plus a fixed camera that captured the landscapes rushing by outside. There is no indication of who shot what, though aficionados of Maysles’ gently probing camerawork might have their suspicions.

All this makes “In Transit” a fascinating study in legacy as well as the gestalt of trains and the personalities of people who ride them. The characteristic Maysles mix of curiosity and compassion is present in every moment of “In Transit.” It doesn’t always feel like the films that Maysles made with and without his brother, but there are times when it does, strongly so, and there are other times when the Maysles touch is apparent even when the film is making choices that Maysles might not have made. And that’s how Maysles would have wanted it, I suspect. In the second half of his life, he was as much a mentor as he was a filmmaker. Among its many virtues, “In Transit” is a moving tribute by students to a master who taught them how to see while encouraging their vision.