They are in the mood for love, but not in the time and place for it. They look at each other with big damp eyes of yearning and sweetness, and go home to sleep by themselves. Adultery has sullied their lives: his wife and her husband are having an affair. “For us to do the same thing,” they agree, “would mean we are no better than they are.” The key word there is “agree.” The fact is, they do not agree. It is simply that neither one has the courage to disagree, and time is passing. He wants to sleep with her and she wants to sleep with him, but they are both bound by the moral stand that each believes the other has taken.

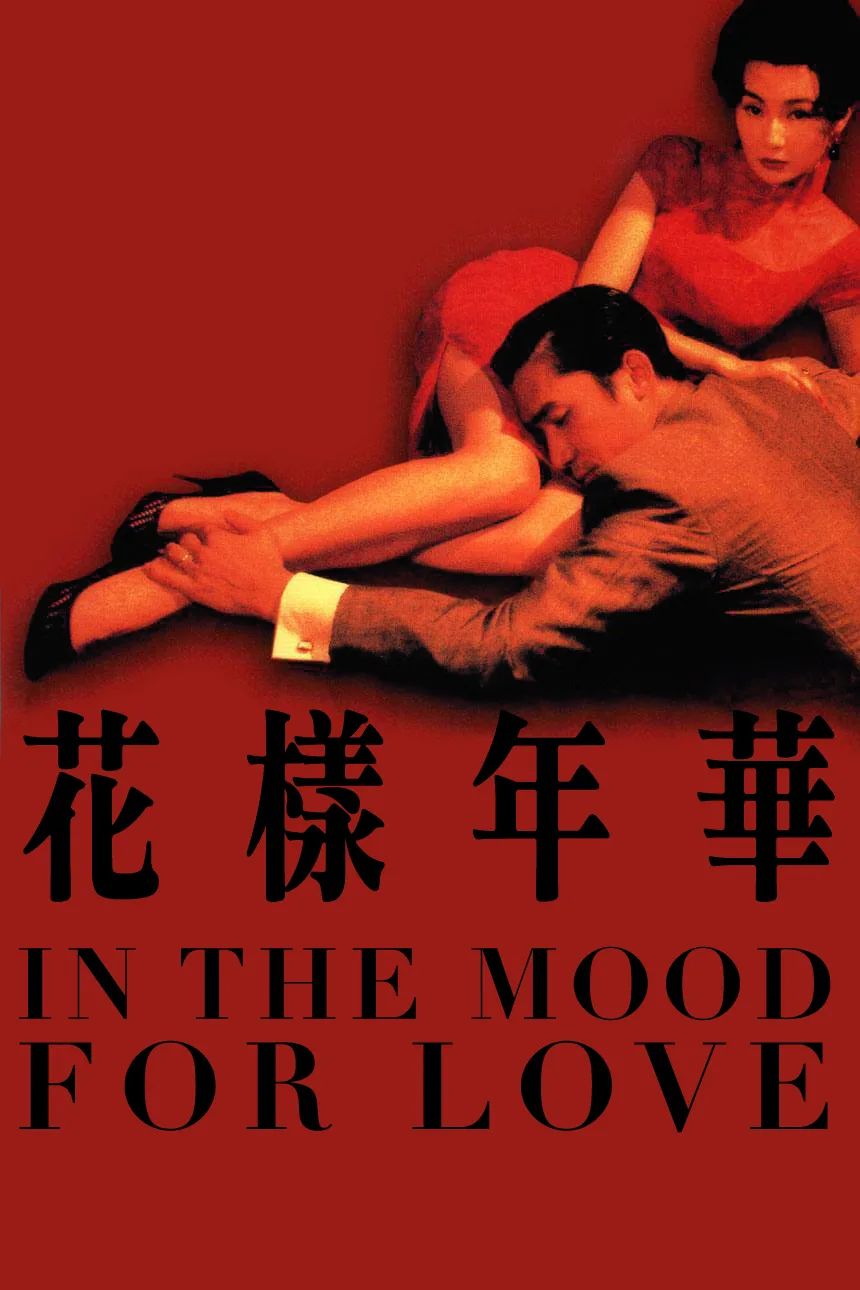

You may disagree with my analysis. You may think one is more reluctant than the other. There is room for speculation, because whole continents of emotions go unexplored in Wong Kar-wai’s “In the Mood for Love,” a lush story of unrequited love that looks the way its songs sound. Many of them are by Nat King Cole, but the instrumental “Green Eyes,” suggesting jealousy, is playing when they figure out why her husband and his wife always seem to be away at the same times.

His name is Mr. Chow (Tony Leung Chiu-wai). Hers is Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung Man-yuk). In the crowded Hong Kong of 1962, they have rented rooms in apartments next to each other. They are not poor; he’s a newspaper reporter, she’s an executive assistant, but there is no space in the crowded city and little room for secrets.

Cheung and Leung are two of the biggest stars in Asia. Their pairing here as unrequited lovers is ironic because of their images as the usual winners in such affairs. This is the kind of story that could be remade by Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan, although in the Hollywood version, there’d be a happy ending. That would kind of miss the point and release the tension, I think; the thrust of Wong’s film is that paths cross but intentions rarely do. In his other films, like “Chungking Express,” his characters sometimes just barely miss connecting, and here again key things are said in the wrong way at the wrong time. Instead of asking us to identify with this couple, as an American film would, Wong asks us to empathize with them; that is a higher and more complex assignment, with greater rewards.

The movie is physically lush. The deep colors of film noir saturate the scenes: Reds, yellows, browns, deep shadows. One scene opens with only a coil of cigarette smoke, and then reveals its characters. In the hallway outside the two apartments, the camera slides back and forth, emphasizing not their nearness but that there are two apartments, not one.

The most ingenious device in the story is the way Chow and Su play-act imaginary scenes between their cheating spouses. “Do you have a mistress?” she asks, and we think she is asking Chow, but actually she is asking her husband, as played by Chow. There is a slap, not as hard as it would be with a real spouse. They wound themselves with imaginary dialogue in which their cheating partners laugh about them. “I didn’t expect it to hurt so much,” Su says, after one of their imaginary scenarios.

Wong Kar-wai leaves the cheating couple offscreen. Movies about adultery are almost always about the adulterers, but the critic Elvis Mitchell observes that the heroes here are “the characters who are usually the victims in a James M. Cain story.” Their spouses may sin in Singapore, Tokyo or a downtown love hotel, but they will never sin on the screen of this movie, because their adultery is boring and commonplace, while the reticence of Chow and Su elevates their love to a kind of noble perfection.

Their lives are as walled in as their cramped living quarters. They have more money than places to spend it. Still dressed for the office, she dashes out to a crowded alley to buy noodles. Sometimes they meet on the grotty staircase. Often it is raining. Sometimes they simply talk on the sidewalk. Lovers do not notice where they are, do not notice that they repeat themselves. It isn’t repetition, anyway–it’s reassurance. And when you’re holding back and speaking in code, no conversation is boring, because the empty spaces are filled by your desires.