Hava Kohav Beller’s “In the Land of Pomegranates” tackles the Middle East’s most intractable, and most publicized, crisis by interweaving two strands of documentary. In one, the film observes a structured dialogue between Palestinian and Israeli young people held as part of a program called Vacation from War. In the other, Beller revisits episodes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict of the last 20 years and focuses on the stories of certain people on both sides.

Combining two separate filmmaking modes like this is a tougher challenge than some viewers might imagine (this reviewer has made a documentary that attempts something similar) and it’s to the credit of Beller and editor Jonathan Oppenheimer that the meshing here is both smooth and productive: the two strands do illuminate each other, creating a dialectic within the film that’s both informative and thought-provoking.

In the cases of both strands, it’s worth noting what is not included. In the sections about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict we see scenes of protests and the chaos on bloody streets following bus bombings, and hear the stories of a few people involved in the situation. But such things are presented in an almost impressionistic manner, and there are very few mentions of political leaders or parties. There are also no talking heads, interviews with experts, or chronological attempts to explain how the political situation evolved in recent decades.

Individual viewers can decide whether the lack of historical context and analysis works for the film or not. But it must be said that if Beller assumed that most people likely to view the film know a fair amount about the subject already, she’s probably right. And not having to offer a lot of distanced explanation allows her to focus on the intimate details of this complex situation.

It’s also worth noting—although readers of this review may already assume this—that the film’s point of view is liberal, Western, humanistic and determinedly even-handed and non-partisan. This is fine—in fact, it may be essential for a film that wants to find common ground and stimulate dialogue—though some on both sides may find it too simplistic and willing to avoid the conflict’s thorniest problems, including the way political influence in the U.S. helps maintain a torturously unjust status quo.

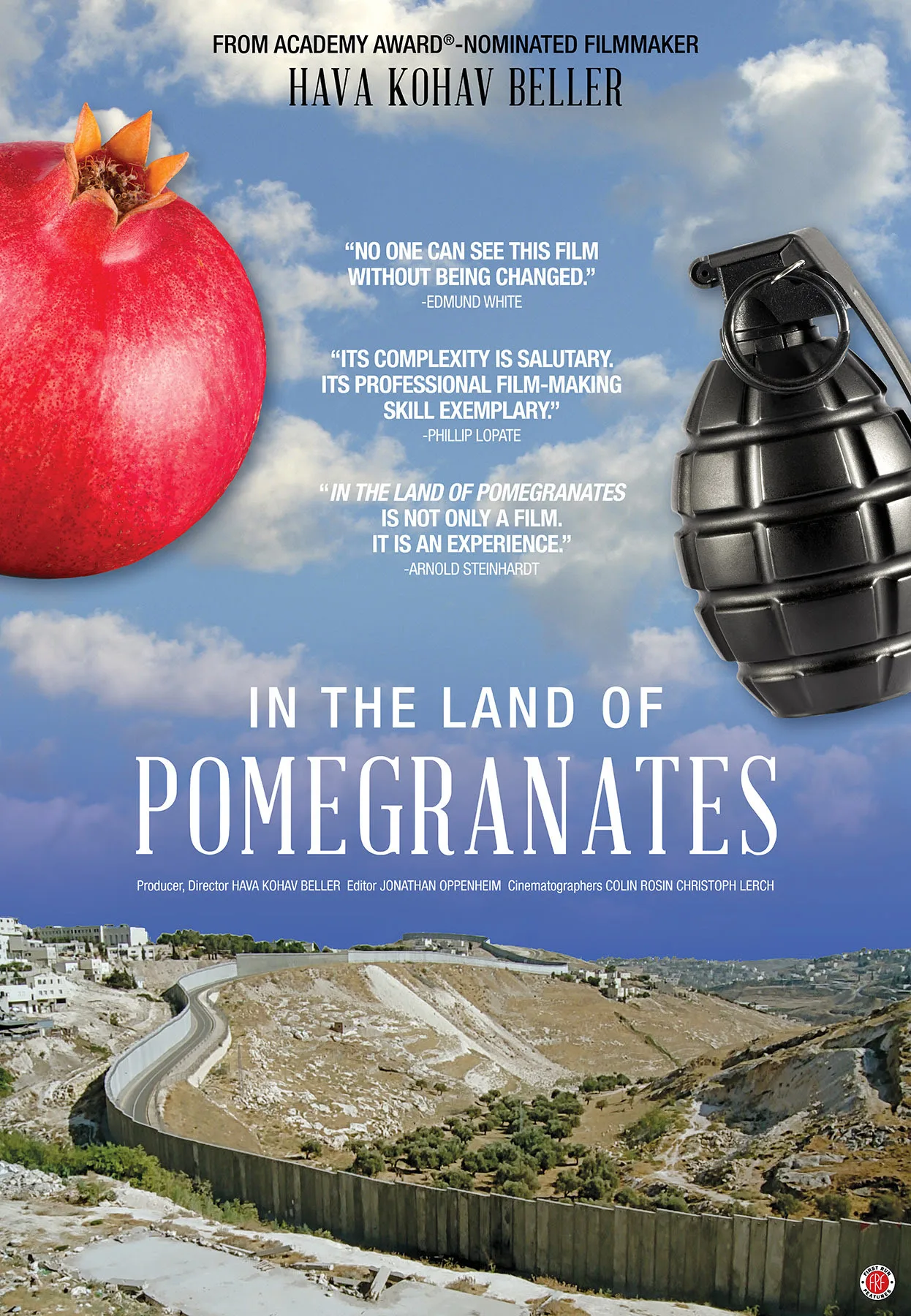

One thing that’s valuable about a film like this is that it shows us places that writing alone leaves too abstracted. Here we get an immediate sense of certain bustling city streets, tranquil farms and other landscapes, perhaps the most piquant and resonant being those that flank the Wall, i.e. the structure that’s called a security fence by one side, an apartheid fence by the other. Nearby, Beller visits a spirited, sardonic Israeli woman who’s painfully aware that she’s chosen to live in a place where her children could easily be picked off by snipers.

Another Israeli is a man who was wounded in a bus bombing some 15 years before. Though his injuries eventually healed, the incident left him damaged psychologically, exacting a heavy toll on his marriage and prompting him to move to the Sea of Galilee in search of tranquility.

Among the Palestinians profiled, the most screen time goes to a mother with a little boy who has a heart problem that requires an operation in an Israeli hospital. While the doctors’ professionalism and gentle solicitousness toward the child are evident here, so are the elaborate barriers that mother and son must clear to go from Gaza into Israel.

The film’s other main narrative strand, the dialogue between young (most appear to be in their 20s) Palestinians and Israelis, takes place in Germany, the event’s organizers apparently having decided that the best results could be achieved away from the zone of conflict. The participants on both sides are mostly bright and appealing, and undoubtedly are moderates within their own communities. One Israeli girl explains how she wanted to turn her back on the troubling conflict, forget it, but then decided she would be better off facing it.

Each side uses the word “narrative” in explaining the different ways they understand the history that has led them to such a terrible impasse. Naturally, there’s a fair amount of suspicion and mistrust going into the encounter. The Palestinians ask one former Israeli soldier if he ever shot anyone. He says no, he only used rubber bullets and gas. They clearly don’t believe him.

More polite and conscientiously civil than emotional or cathartic, these discussions don’t yield any surprising results, and we don’t learn if they resulted in any lasting friendships. Yet it’s interesting to witness the encounter and hear the thoughts of young people from such a bitterly divided land.

The film tells us almost nothing about Vacation from War, but I gather it is run by the Anna Lindh Foundation, an intergovernmental organization designed to foster civil societies and understanding among Mediterranean countries. It would be interesting to know more about how it is run: how the participants are chosen, how the moderators understand their jobs and measure their success or lack thereof, and what follow-up is done. But that, no doubt, would be a different film.