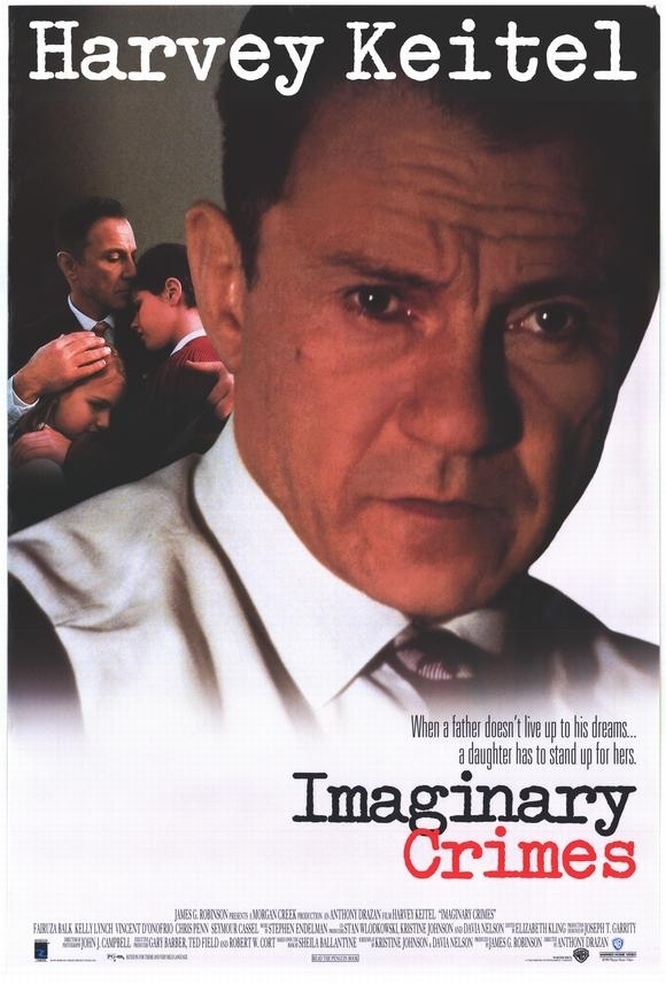

Ray Weiler, the character played by Harvey Keitel in “Imaginary Crimes,” is a con man. He spins fabulous stories of vast deposits of gold and uranium, just waiting to be harvested, and talks investors into sinking money into his foolhardy schemes. He is usually just this side of the law. Occasionally he strays to the other side; it is not a distinction that means much to him, since he knows in his heart that success is just around the corner.

It is important that we understand that about his heart: that in some fundamental way, Ray really does believe in his dreams.

Like many great con men, the person he has conned most thoroughly is himself. He has certainly not conned his two daughters, Sonya and Greta, who have lived through so many of his schemes that they are openly dubious about almost everything he says.

Ray is a widower, trying to raise the two girls – the older, played by Fairuza Balk, who is a gifted high school student, and the younger (Elizabeth Moss), who is learning fast. Their late mother (Kelly Lynch) is seen in flashbacks, looking dubious as Ray unveils gadgets that are “going to revolutionize the mining industry.” Now, the family of three stays one step ahead of the landlord and the bill collectors, and the girls are skilled at not answering the door, and letting the phone ring.

“Imaginary Crimes,” based on an autobiographical novel by Sheila Ballantyne, is one of those movies like “King of the Hill” or “This Boy's Life” that show children adapting to the difficult circumstances of their home life – to parents who are distant or difficult – and surviving. It regards Ray, the Keitel character, as neither monster nor lovable character, but simply as a very difficult case. And it suggests that in many ways the girls benefitted by having such a strange father – although, of course, his behavior is not admirable.

Ray is the central character, but Sonya is the one through whose eyes we see, and she is played by Fairuza Balk as a strong, outgoing, realistic girl, who has secret dreams of being a writer.

She is encouraged by her high school English teacher (Vincent D'Onofrio), who reads her stories of chaotic family life and guesses that they are based on fact. He encourages her to attend college, and when she says, “You don’t know my father,” he shyly says, “Well, in a way, I do.” Sonya of course has a crush on the teacher, and spies on him at home, but the movie doesn’t move in an obvious direction; she isn’t perceived as troubled, and he isn’t seen as improper in his behavior toward her. Instead, he is like so many good teachers who at a crucial point in a student’s life can give just the right push.

Meanwhile, Ray’s business schemes are going from bad to worse. His long suffering partner (Seymour Cassel) half-believes that a new tract of land does contain mineral wealth, and so does their investor, Jarvis (Chris Penn). But Rayhas not quite obtained all the rights he says he has, and Jarvis can be a dangerous man. (Penn plays the role on the right note of concealed menace; like his brother Sean, he can be quietly powerful).

The obvious points of the movie are made quickly: That Ray is a liar and a con man, and his daughters are being raised in a world of self-deception and uncertainty. The deeper points emerge more slowly: When there is real love in a family, it can absorb many wounds. As Sonya’s teacher wryly tells her one day about her father, “He is one hell of a source for material, isn’t he?” Here is the movie to prove it.