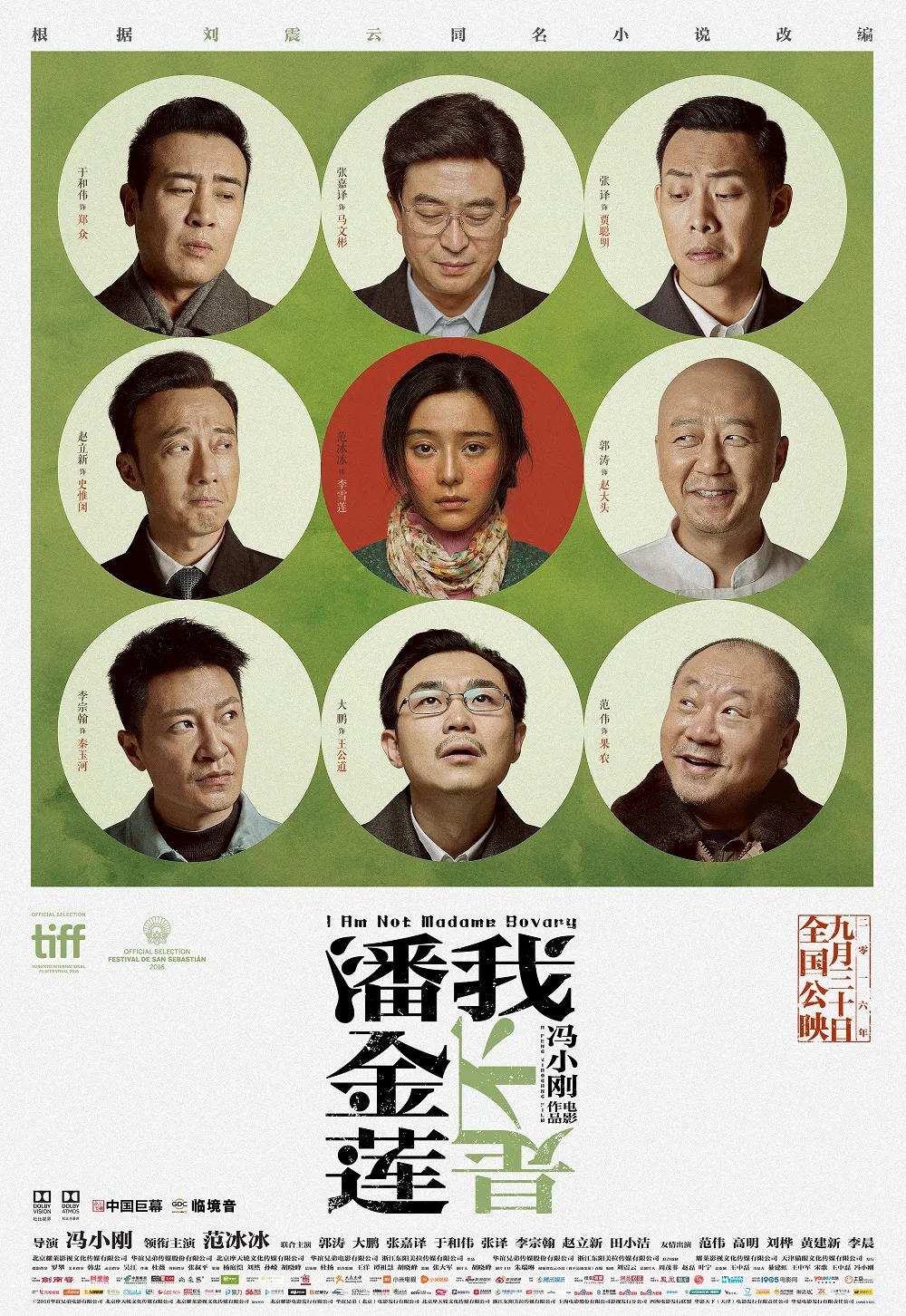

Director Feng Xiaogang‘s “I Am Not Madame Bovary,” with Fan Bingbing as the central character, is not a re-telling of Gustave Flaubert’s vicious send-up of the French bourgeoisie. As the male voiceover informs us at the outset, as though he is launching a solemn bedtime story, the film is based on a 17th-century Chinese morality tale about an unfaithful wife named Pan Jinlian who conspires with her lover to kill Pan Jinlian’s husband. And ever since that day, “bad” women, are referred to as “Pan Jinlian.” It is a scarlet letter. The title of the film was apparently chosen because “Madame Bovary” has the same connotations to Western audiences that “Pan Jinlian” does to Chinese audiences. “I Am Not Madame Bovary,” though, is not about infidelity or the lowly position of women. The real story is about the nature of bureaucracy, and one woman’s tireless attempt to go up against The System. This makes the film sound weighty and political, but “I Am Madame Bovary” plays out as a comedy, a lampoon of the incompetence and laziness of government officials.

The first scene shows peasant woman Li Xuelian (Fan) visiting her cousin—who knows about legal matters—to ask him what recourse she has in terms of getting a divorce. Her story, rattled off to him, is incredibly complicated, and he looks more and more confused: she and her husband, trying to game the system, faked a divorce, complete with phony divorce papers, so that one of them would be eligible for the apartment they both wanted. The plan was that they would reunite eventually when Li Xuelian got pregnant and then they both could live in that apartment. The husband broke the rules of their plan, however: he fell in love with someone else during this time (treating his “fake” divorce as real, in other words), and he and his new “wife” moved into the cherished apartment, leaving Li Xuelian out in the cold. Her cousin suggests she present her case to the local court, which she does. They don’t get it. (I don’t blame them.) She is not put off easily. Her husband has put her in a horrible position and she needs to clear her name. She is no “Pan Jinlian.” And so begins her legal journey, as she sues each person who refuses to help her, eventually suing people all the way up to Beijing. She is a royal pain to the various county chiefs and judges and mayors: she races out in front of their cars shouting “Stop!”, she holds up a sign and sits in the street outside of their offices. She appears at their conferences in Beijing like clockwork. They dread seeing her.

The State, as shown in “I Am Not Madame Bovary,” is not quite as oppressive as Airstrip One in 1984, but it is still a gigantic monolith. The film is crowded with obsequious toadying officials, mediocre bored bureaucrats, and ambitious nobodies covering their asses. They are all men, of course. Despite their power and status, each one eventually throws up his hands in helplessness at her relentlessness. Her behavior doesn’t quite equal the absurdities of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, the court case spanning generations in Dickens’ Bleak House, but it does have a similar almost existential quality. Why won’t they just give her what she wants so that they will leave her alone?

“I Am Not Madame Bovary” clocks in at almost two and a half hours, a pretty brutal length for a story so repetitive. Li Xuelian barely has a life outside of her quest. Everything she does is because she wants to clear her name. She has a strange romance with a childhood friend who has pined for her for years, but even within that, she has one goal and one goal only. It’s the principle of the thing to her.

Feng Xiaogang has chosen a distancing device for his visuals. The rural sections of the film are seen through a circular shape, cutting off the periphery of the screen, giving the impression that we are observing the action through a telescope. Or a rifle-sight. When she gets to Beijing, the circular shape vanishes, and suddenly the frame is a perfect square, representing the much larger world she enters. The circular shape limits the amount of movement possible on the screen, and group scenes in particular suffer because of that. There’s a stilted quality to the interactions, and everyone stands in one spot like statues. The intention is to create the effect of an old Chinese painting, the ones seen in the opening of the film underneath the voiceover. This style must have required extreme rigor on the part of everyone involved to keep the action contained enough to stay inside that circle. Much of the film is stunning. These are moments in miniature, seen through a peephole. The color scheme is careful and poetic: watery greens and greys and blurring pinks in the countryside, while Beijing is all gold and red and white. Since much of the film involves Li Xuelian going back and forth from city to country (accompanied by a thrilling percussive score by Wei Du), there is a constant circle-to-square-scene change-up for the action. Feng’s style excludes close-ups almost exclusively; the strict framing does not permit it. The overall effect is so distancing that it’s as though the characters are at the bottom of a well.

There’s not an uninteresting or boring shot in “I Am Not Madame Bovary.” It’s a pleasure to look at the screen and to watch the artistry of the entire creative team. But there’s a forbidding quality to the entire enterprise. That circular frame is way too small to squeeze through.