It’s obvious that the yogurt is reading his mind, right? Right? Hello? For Shadyac and the technician, this experiment demonstrates that our minds are wired to the organic world. For me, it raises the following questions: (1) Was the yogurt pasteurized? (2) How did the yogurt know to read Shadyac’s mind and not the mind of the technician who was just as close? (3) How did it occur to anyone to devise an experiment testing whether yogurt can respond to human thoughts? (4) Did anyone check to see if the technician was connected to the meter by? (5) Is this a case for the Amazing Randi?

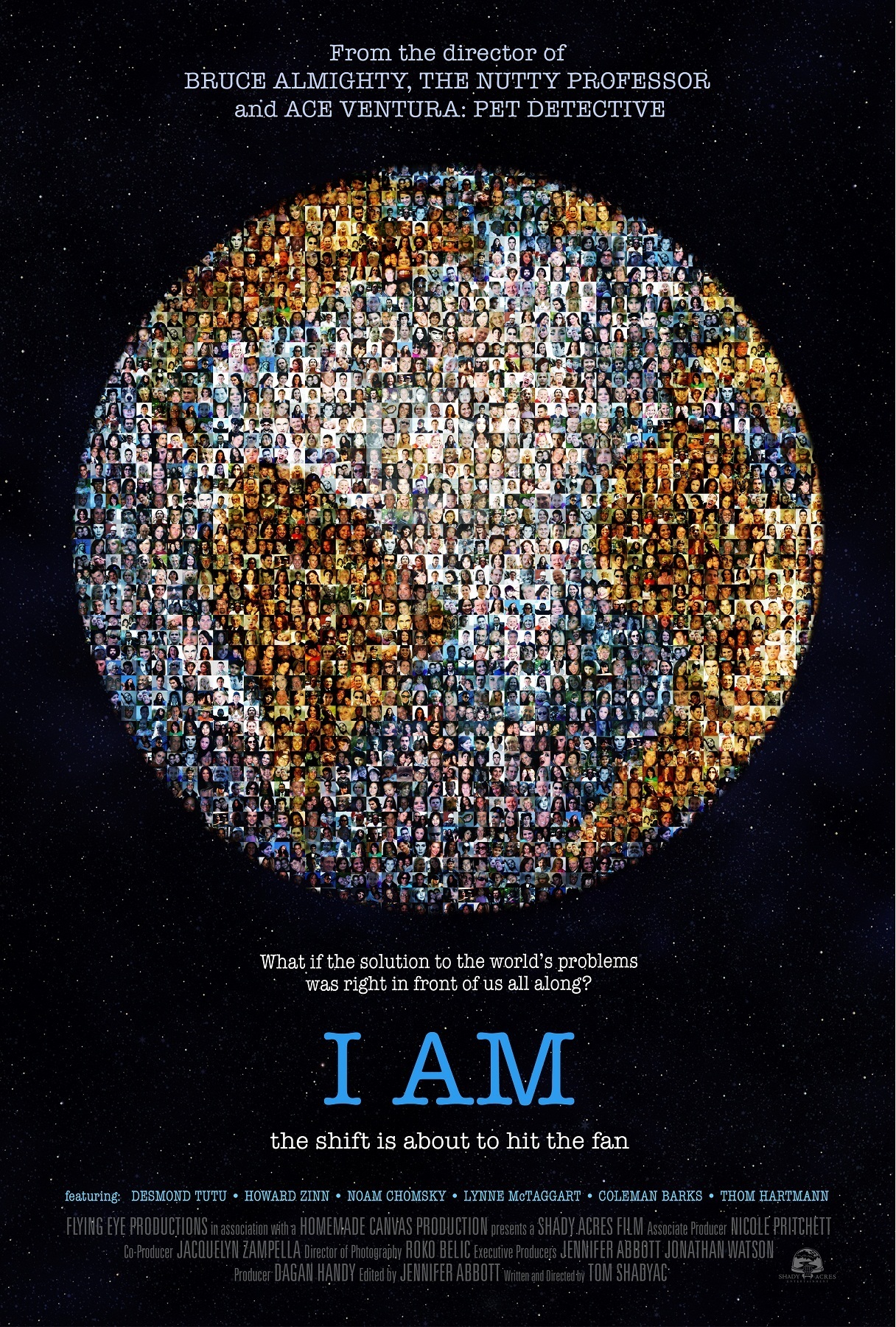

You see I am a rationalist. That means I’m not an ideal viewer for a documentary like “I Am,” which involves the ingestion of Woo Woo in industrial bulk. When I see a man whose mind is being read by yogurt, I expect to find that man in a comedy starring, oh, someone like Jim Carrey. Since we all understand There Are No Coincidences, it won’t surprise you to learn that “I Am” was directed by Tom Shadyac, who earned untold millions by directing Jim Carrey in such films as “Ace Ventura, Pet Detective.”

This film is often absurd and never less than giddy with uplift, but that’s not to say it’s bad. I watched with an incredulous delight, and at the end, I liked Tom Shadyac quite a lot. He’s a goofball, yet his heart is in the right place. But don’t get me started on hearts. Did you know that Shadyac’s friend, Rollin McCraty, director of research for HeartMath, has proven that the human heart controls the human brain via various types of biofeedback?

That’s not all the heart can do. Try this on for size: When you are shown pleasant or frightening images on a computer screen, your brain (and heart) respond either positively or negatively. That makes sense. But wait. When the images are chosen at random from a big database, the heart sends positive or negative signals to the brain two to three seconds in advance of the image being chosen. In other words, the heart knows what the random image is going to be. Yes. Shadyac is grateful for this information. He doesn’t ask any questions, like, for example, does the heart tell the brain what signal would have been displayed unless the power to the monitor went out in the milliseconds between it was chosen and was to be displayed?

McCraty shares another piece of information that’s interesting. There are random number generators distributed all over the world. Most of the time the numbers are truly random. But when a global catastrophe like 9/11 or the Japan calamity occurs, our collective minds send out such strong signals that the computers temporarily stop selecting random numbers. Yes. And the screen fills with lots of ones and zeroes to illustrate that.

So I’m thinking, not everybody found out about the Japan earthquake at once. Does McCraty have data showing if the globe’s random number calculators failed simultaneously, or were timed to the spread of the news? (I can guess the answer: They all failed at once, because at a Gaia level, we all sensed it simultaneously.)

What set Shadyac to gather this information and make a film about it? In 2007, he was a multimillionaire living in a 17,000-square-foot mansion in Pasadena and flying in a private jet. Then he had a terrible bike accident, breaking bones and suffering a concussion. He became a victim of Post-Concussion Syndrome, had blinding headaches and debilitating depressions and contemplated suicide. Mercifully, the symptoms faded, leaving him sadder, wiser and in search of truth.

He began with two questions: What’s wrong with the world? What can we do about it? He traveled around the globe to pose these questions to distinguished men such as linguist Noam Chomsky; Archbishop Desmond Tutu; his father, Richard Shadyac, who was CEO of St. Jude Hospital’s fund-raising division, and so on. None of them necessarily agree with anything the others say. As for Shadyac, hey, he’s just listening.

The thing is, he doesn’t ask enough. He is not a skeptic. He asks his two questions and mashes together the answers with a lot of fancy editing of butterflies, sunsets, flocks of birds, schools of fish, herds of wild animals and Petri dishes filled with yogurt. From his tour emerges one conclusion: Everything is connected. Our minds, our bodies, our planet, our universe. This happens (you can see this coming) at the quantum level.

Another thing he learns is that money is the root of all evil. Like the fish, birds, animals and untouched tribes, we have evolved to cooperate and arrive at consensus. By competing to enrich ourselves, we create bad vibes. Give Shadyac credit: He sells his Pasadena mansion, starts teaching college and moves into a mobile home (in Malibu, it’s true). Now he offers us this hopeful if somewhat undigested cut of his findings, in a film as watchable as a really good TV commercial, and just as deep.