What we are getting here is Hefner as he wants to be remembered. He says that, in a way, he wrote his “Playboy Philosophy” in the 1960s to explain himself to his mother. His mother is still alive, at 97, and maybe this movie is for her, too. Hef was raised in a strict Methodist home with old-fashioned values and no hugging, and after decades spent in reaction to that upbringing, he has come full circle and is now the head of a family with a pop, a mom, two sons, and maybe a baby sister on the way. Mom is the 1988 Playmate of the Year, of course, but lots of guys meet nice girls at work.

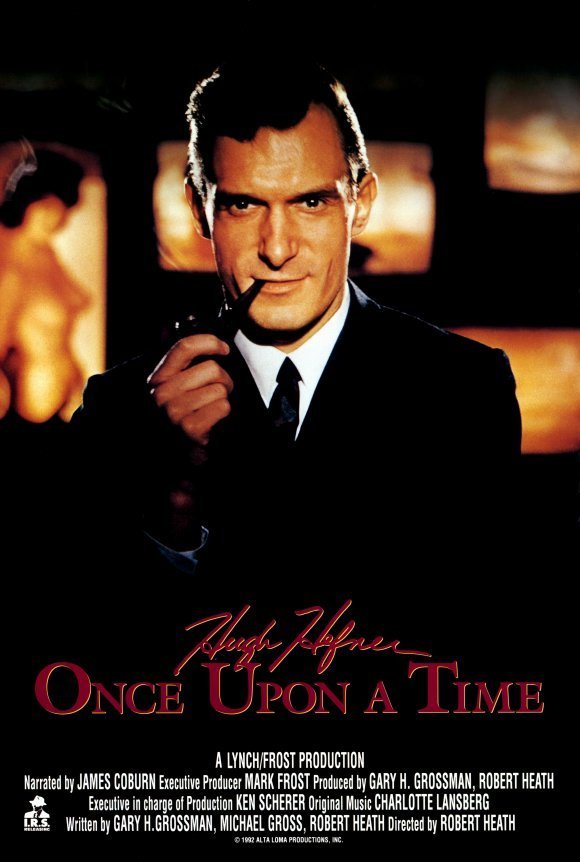

The movie’s style is smooth and professional. James Coburn’s narration sounds like an ad for a luxury car. But the materials of the movie are very personal: Childhood snapshots, home movies, yearbook pictures, Hef in high school, Hef in college, Hef at his first job, Hef inventing the Playboy mystique and living right at the heart of it, and finally Hef growing older, as we all must, and having a stroke that slaps him in the face with his mortality, and then, in his 60s, marrying a second time and starting a second family. Full circle.

There are two sequences in the film that contain, I believe, the key to Hefner’s public persona. We learn that as “Hugh” he was shy and unpopular the first two years in high school, and then he “reinvented” himself – the word is in the movie – as “Hef,” the high school wit and cartoonist, actor and editor, who made the others laugh and entertained them. All the time he was at one remove from this process, turning himself and his friends into cartoons (there are several shots in which high school photos dissolve into his Archie & Jughead caricatures of the same friends).

It was a role that suited him, and later we see him presiding over parties at the Playboy Mansion – where, one of his friends recalls, “there was a bar, but Hef didn’t drink. There was a fabulous buffet, but you never saw him eating. It was all for his friends.” Hefner himself says, over and over, that his last two years of high school were the happiest years of his life. And there you have the key: Hefner’s Playboy image was an extension of Hef, the upperclassman at Chicago’s Steinmetz High school, throwing neat parties for his friends with lots of good eats and drinks and movies and pop music – and as the friends had a great time, Hef stood back and watched, and recorded it all in his magazine.

“Classes were great at Steinmetz,” Hef told the students during a visit there last week, “but extracurricular activities were fabulous.” It was the same in the magazine: The articles and interviews and political controversy were the classes. They were good. After class was out, there were the Playmates and the party jokes and the recipes for exotic libations and the specs on new sports cars. And instead of going over to Hef’s house after school to spin some platters, Hef’s new classmates (his readers) were invited, symbolically, over to Hef’s mansion.

Jules Feiffer, an early guest, observes in the film that he dreamed of bedding dozens of Playmates, but never had sex in the mansion. His story is revealing. If the image was of a nonstop orgy, the reality was more like a 1940s after-school party, in which the guys could look at the girls and dream, but in the meantime there were pinball machines and a pool, a bowling alley and a neat firepole to slide down, movies and a hi-fi system, and permanent icebox-raiding privileges. The Playmates were, literally, well-named.

The party lasted from the late 1950s until the late 1980s, but all of the times were not good. The movie goes into some detail about the two great tragedies of the Playboy story, the suicide of Hefner’s private secretary, Bobbie Arnstein, in the midst of a drug probe, and the murder of Playmate of the Year Dorothy Stratten by her insanely jealous husband. Arnstein was charged with buying and selling cocaine, and Hefner argues in the movie that, while she did use cocaine, she was targeted only because a politically motivated prosecution was after bigger game, and wanted her to testify against Hefner. She refused to, and, facing jail, killed herself. Later the probe was dropped, with no charges ever filed.

Hefner does not say in the movie whether he ever used cocaine. Drugs in general were discouraged at the mansion because of the legal risks, but Hefner admits to an addiction to pep pills that kept him working for 40-hour stretches. His drug use was the opposite of recreational; until the stroke he was a workaholic.

The Stratten story is more complex because Dorothy was in love with movie director Peter Bogdanovich at the time of her death, and Bogdanovich wrote an anguished book blaming her death on the Playboy mystique. Not true, Hefner says; she had outgrown her sleazy boyfriend and he might have killed her if Playboy had never existed.

What if Playboy had never existed? Would we live in a different world? Possibly. Historians will someday conclude, I believe, that for better or worse, Playboy was the most influential magazine of its time. “Hugh Hefner: Once Upon a Time” gives the Founder’s view of that phenomenon. There are many other views, some far less favorable. But American society was never quite the same after we all went over to Hef’s house after school.