At one point in Maria Sødahl’s superb drama “Hope,” which concerns a woman facing the onset of an illness diagnosed as terminal, a doctor describes treating cancer as “like peeling an onion.” The same might be said for the film itself. Though the story’s medical premise is quickly announced, what follows peels back layer after layer of human realities that science can’t begin to describe, beginning with the shock and disorientation the diagnosis initially provokes and continuing through the deeper realizations and understandings gradually faced by the woman, her partner, their kids, friends and extended family. These carefully unveiled discoveries make “Hope,” Norway’s submission for this year’s Best International Feature Film Oscar, one of the year’s richest and most rewarding contemporary dramas.

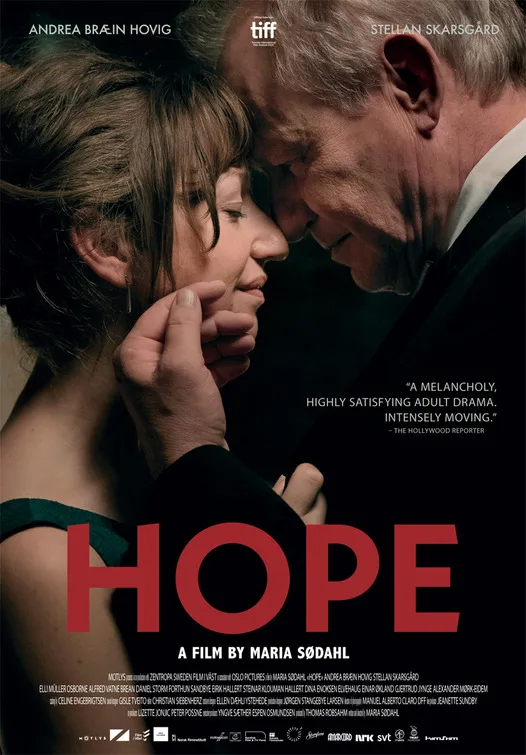

The story comes from writer/director Sødahl’s own life. Several years ago, she was diagnosed with terminal cancer, putting a sudden stop to a promising career. Obviously, she not only survived but used the rupture in her life to look back on the experience and what it taught her about herself and her closest relationships. That real-life basis helps give “Hope” a palpable aura of authenticity that extends down to its smallest emotional details. It also no doubt accounts for the grace notes of humor and lyricism that add to the artistic power of Sødahl’s achievements as writer and director, and her work with two extraordinary actors, Andrea Bræin Hovig and Stellan Skarsgård.

Set around the Christmas and New Year’s holidays, “Hope” probes the relationship of two successful creative types. Anja (Hovig) is an acclaimed choreographer who’s just returned from her first foreign success when her doctor delivers the bad news: though she survived a bout of lung cancer the year before, she now has a tumor in her brain. It is certain to be terminal, she’s told, though it may still be operable (further tests and consultations with doctors will crowd the following week). While the diagnosis surprises and upsets Anja, it seems to stun her partner, theater director Tomas (Skarsgård), into a frozen, disbelieving silence.

The unmarried couple oversee a brood of six children ranging in age from ten to mid-twenties: the older three are from his previous marriage, the younger three from their union. Not least among the film’s accomplishments is Sødahl’s way of deftly describing these young people in ways that make them individually distinctive yet also part of a believable family structure. And they are paramount in Anja’s concerns when she begins to process the doctor’s news. Even as she gets buffeted by the effects of drugs that make her both high and volatile, she begins to agonize over the question of who will care for the kids when they lose their mother.

More pressing still is the dilemma of when and how to tell them the news. Last year this time, she revealed she had lung cancer but the doctors were hopeful of treating it. This year, the news offers far less room for hope. If she’s forthcoming, she wonders half-jokingly, will it ruin Christmas for these kids forever after?

In peeling away the layers of Anja’s concern for the children and also her aged father, who’s visiting, Sødahl zeroes in on the heart of this emotional crisis: the relationship between Anja and Tomas. The more we learn of it, the more brittle it seems. At one point, she reveals that she was on the verge of leaving him a year before, only to be stopped by the previous cancer diagnosis. Told that she probably has only a few months left to live, she now seems zealous to probe her bond with Tomas to see what truth it contains, what lies. Have they been faithful to each other, or not? She admits to loving a man she didn’t pursue. Tomas sheepishly confesses to one long-ago “fling,” but says her real rival was his work.

That seems to be the most accurate diagnosis of what ails this union at is deepest level, and the fault is clearly not on his side alone. Both partners have allowed careers and kids to draw them away from each other, to the point that their life together ends up being all too perfunctory, with each one dissatisfied yet unable to express or overcome that unhappiness. But now a seemingly incurable disease forces them to face their deepest feelings for each other, and to ask whether there’s real love behind the charade of love they’ve been living.

In some ways, “Hope” calls to mind searing Bergman marital dramas like “Scenes from a Marriage,” but Sødahl’s touch is altogether lighter. Her pleasingly naturalistic style, abetted by Manuel Alberto Claro’s beautifully nuanced cinematography, gives scenes and moments room to breathe, allowing viewers to absorb the textures and flavors, moods and rituals of Anja and Tomas’ spacious Olso apartment, with its never-ceasing flux of people, meals, and silences. Most of all, her directorial skills undergird the power of two of the most remarkable performances I’ve seen in a film this year.

I’d never encountered Hovig’s work before, but here it’s striking for both the vulnerability and the gut-level strength she gives Anja. There’s an essential physicality to her performance—you believe the affliction’s effects on her body—that grounds the emotional rollercoaster ride her situation takes her on. And while Skarsgård’s excellence is a dependable virtue in his distinguished career, playing Tomas brings out his most subtle skills, his ability to convey a wealth of complicated emotions in a glance, a shrug, a wince.

To be sure, cancer may not sound like an inviting cinematic subject, especially to families and individuals who—like this writer—have been faced with its sometimes-overwhelming trials. Yet the effect of “Hope” is anything but depressing; it’s reassuring proof of art’s ability to comfort as it clarifies. For my money, it’s a better film than the Scandinavian comedy that seems destined to win this year’s international feature Oscar. But Thomas Vinterberg’s “Another Round” has the advantage of being one for, by and about “the boys,” while Sødahl’s triumph belongs to a more forward-looking story—the ascent of brilliant female auteurs. It should not be missed.

Now playing in select theaters.