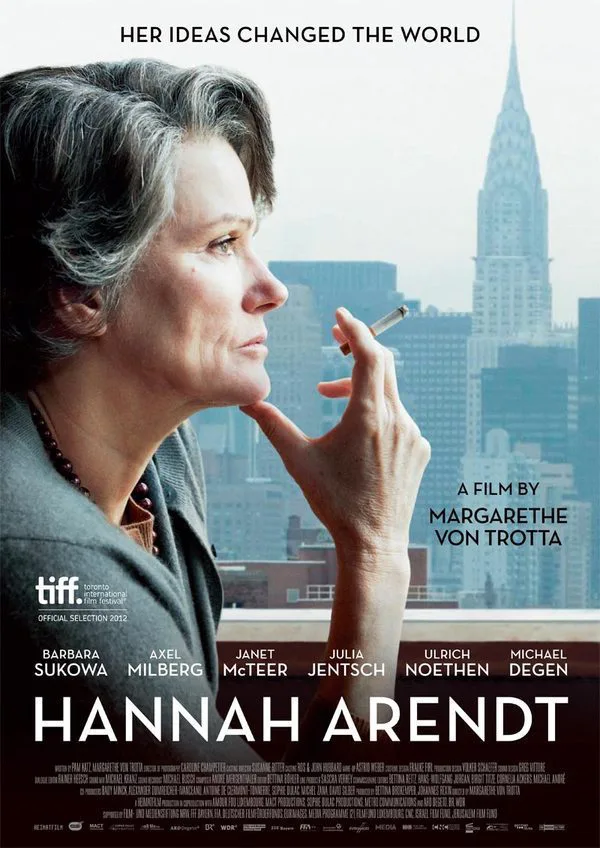

“Hannah Arendt,” German director Margarethe von Trotta’s new film about the titular political theorist with Barbara Sukowa in the lead role, is an old-fashioned biopic. It forms a loose feminist trilogy with the director’s 1975 debut “The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum” and her 1986 film “Rosa Luxemburg.” That the latter also starred the formidable Sukowa only adds to the association. Even though the director constantly refuses the description, von Trotta remains one of cinema’s great feminist auteurs. Her films tend to have a sense of immediacy reminiscent of the glory days of second wave feminism. She tends to bring forth a humanist approach towards the struggles of her subjects, which is a particularly impressive feat in the case of “Hannah Arendt,” since the philosopher was anything but a feminist.

Arendt is best known for coining the phrase “the banality of evil” in her coverage for The New Yorker of the 1961 trial of former Nazi Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. A self-confessed follower of the Führerprinzip, or Leader Principle—the central tenet of the 3rd Reich’s philosophy that Hitler’s commands stood above all laws—Eichmann infamously adopted the “Nuremberg defense” during the trial, arguing that he was only following orders, and that he could not possibly be charged with war crimes. Rather than taking umbrage at his confessional, Arendt, a former German Jew who’d fled to America from Nazi tyranny, argued that, far from being maniacal sociopaths with ungodly desires, the Nazis were mainly a bunch of pen-pushing bureaucrats, intent on furthering their careers rather than being devoted to some sort of supreme, fanatical ideal. As such, the atrocities committed against European Jews during the war took on a far more horrific, and universal, meaning: appropriately motivated, all humans were capable of inhuman acts.

Hannah Arendt was one of 20th century’s greatest thinkers, and her books “Eichmann in Jerusalem” and, in particular, “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” remain fascinating. Von Trotta’s film, however, is not so much interested in Arendt’s political theories, preferring to view her as the embodiment of the strength and wisdom of the Jewish survivor. It’s perhaps a safer way in which to deal with Arendt’s legacy, as a fictional account could never do it justice. Still, the film remains true to Arendt’s stubborn vision, as it portrays her inner, personal conflicts with a nuanced touch.

The film opens with the apprehension of Eichmann in Argentina by undercover agents of Mossad and the Shin Bet, Israel’s security service. This makes headline news all over the world, including in New York, where Hannah Arendt is living with her husband Heinrich Blucher (Axel Milberg) by her side. Her pitch to cover the trial is accepted by The New Yorker‘s editor William Shawn (Nicholas Woodeson).

In Jerusalem, Hannah is met by her old friend Kurt Blumenfeld (Michael Degen), who informs her that Eichmann comes across during the trial as a nobody, which is the spark she needs for her ultimate theory on the nature of evil. Arendt eventually comes to the conclusion that by following the Führerprinzip, Eichmann was in fact imbuing himself with a sort of blank moral slate. The film doesn’t quite explore this, but one can’t blame it for shying away. It’s a complicated concept.

Arendt’s findings and her articles eventually bring out the worst in everyone, including Hannah, who finds herself surrounded by formal colleagues and friends who are now out to get her. Occasional flashbacks to her university tryst with the philosopher-cum-Nazi Heidegger (Klaus Pohl) fuel her internal struggle, especially an egregiously on-the-nose scene when the philosopher tells Hannah (played in flashbacks by Friederike Becht) that “thinking is a lonely business.” It’s hard out there for an iconoclast.

“Hannah Arendt” is not a particularly subtle picture, nor is it that original. However, Von Trotta’s direction is assured and the film has an incredibly strong performance at its core, and it asks a number of important questions, even though it doesn’t dare to answer them.