In the world of crime novels, the “police procedural” is a subgenre with rigid ground rules. The classic procedural doesn’t much care who’s good or bad, what’s right or wrong: It cares only about the methods by which the police investigate the crime. The best of them are so specific in their attention to details that they even seem to transcend cultural boundaries. Ed McBain, the hard-boiled author of the 87th precinct novels, once wrote a thriller named King’s Ransom, which was filmed in Tokyo by Akira Kurosawa, the great Japanese director, as “High and Low” in 1963. The focus was still on specific details of police work: tracing stolen cars, narrowing down a list of suspects, examining witnesses.

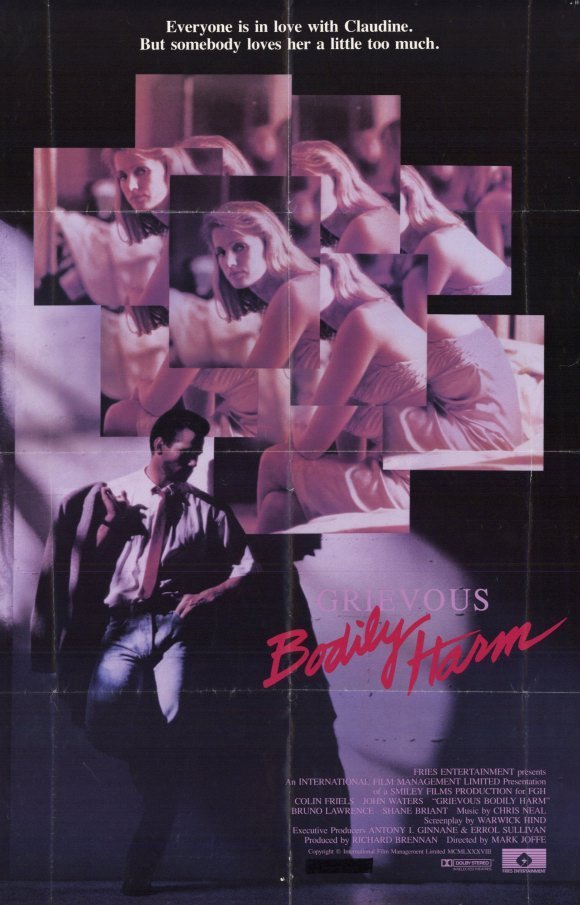

There is a subset of the classic procedural that is a good deal more flexible, however. You could call it the “civilian procedural,” in which the investigative work is carried out by reporters, lawyers or zealous laymen instead of by cops. “True Believer” has lawyer James Woods solving an eight-year-old murder, and now here is “Grievous Bodily Harm,” from Australia, with a freewheeling investigative journalist on the trail of an obsessed killer. The basic difference between the two kinds of stories is that the cops start out as hardened professionals and come to care deeply about the case, while the civilians usually get involved out of emotion and end up cynical.

Take Tom Stewart (Colin Friels), the ace crime reporter for the Australian, for example. He exists in the shadow-world between crime and law, and “Grievous Bodily Harm” opens with a sequence in which he essentially steals the loot from a bank heist from a dying robber. Then he gets involved in another case. A series of murders have been committed, and they all seem to lead back to the same man.

Because the movie uses an omnipotent point of view, we know who the man is. His name is Morris Martin (John Waters), and he is still obsessively in love with a beautiful blond hooker who died, apparently, in a traffic accident in Paris. One night he spots her in a disco, however, and his attempts to follow her lead to the brutal deaths of anyone he suspects is covering up.

A tough, shady vice detective (Bruno Lawrence) is assigned to the case. He has been an inside contact for the reporter in the past, but now they find themselves racing each other to the solution of this crime, and the chase gets complicated when the reporter meets and is attracted to the hooker (Joy Bell). It is also complicated because the cop eventually comes to suspect that the reporter has received the missing loot from the bank job.

Mark Joffe, the director, has several stories to tell, all of them with their own supporting characters, and at first we’re a little confused by events. His film is meticulously constructed, however, so that if we sit tight and watch everything eventually makes sense. The sex-obsessed killer is a creepy, pathetic creature, but the people on his trail are flawed, too, and in the time-honored procedural tradition, the movie is more about what they do, than why.

One of the film’s strengths is a vivid use of locations, from an isolated and expensive bordello to a shabby rural gas station. It also has the usual penthouses, saloons and police stations, obligatory in any film noir. And there is a certain corrupt familiarity in the relationship between the cop and the reporter, based on their mutual knowledge that neither one can be trusted. Lawrence, that tough Australian actor from “Smash Palace,” is cold and unyielding as the vice cop, and Friels is interesting as the reporter: He’s smart and has an engaging personal style, but is pregnant with the willingness to compromise.

“Grievous Bodily Harm” is directed with hard-edged efficiency and a meticulous attention to detail, all the way up to the final sequence. Then it goes soft in the head. Can anyone who has seen the film please tell me exactly what the cop and the reporter are really saying to each other at the airport gate? How much the cop knows about the bankbook that turns up in the final moments of the movie? What the point was? When you base a movie on the painstaking accumulation of detail, you can’t get sneaky at the end. Half the satisfaction of a procedural is in seeing how predictable actions result in an inevitable outcome. That’s the whole problem with allowing civilians to get into the act.