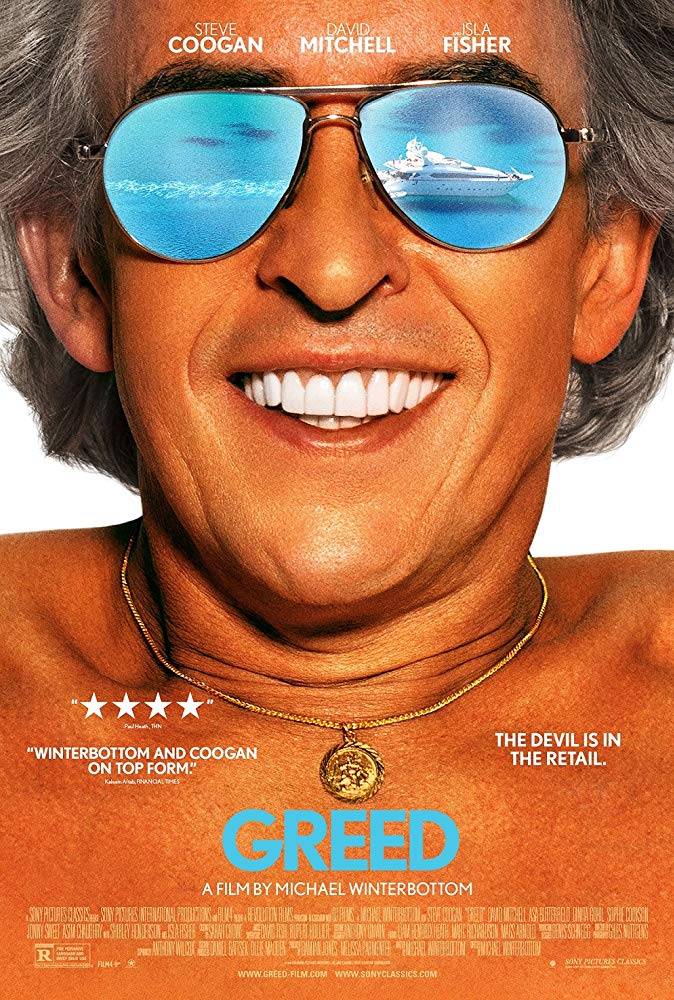

“Greed” is what you get when intelligent, righteously pissed-off filmmakers try, sometimes successfully, to make an acidic black comedy about late capitalism. “Greed” is often as fun as that sounds, despite its generally sympathetic criticisms of class-less business tycoons like Sir Richard “McGreedie” McCreadie (Steve Coogan), a Trumpian fashion mogul based on real-life billionaire Sir Philip Green. McCreadie’s a great character, and writer/director Michael Winterbottom (“Tristram Shandy,” “The Shock Doctrine”) once again brings out the best in Coogan, whose comic timing, physicality, and line delivery make McCreadie’s thuggish behavior very funny. But “Greed” is never the sum of its best parts since other actors—especially Jamie Blackley, who, playing young McCreadie in a series of flashbacks, is fine but relatively disappointing—can’t pull off the movie’s delicate balance of broad humor and po-faced drama.

“Greed” is presented as a hagiographic McCreadie biography gone wrong, commissioned by its proudly exploitative subject but written by blinkered freelancer Nick (David Mitchell), a sap who only realizes how vile McCreadie is while he conducts research. Nick’s editorial commentary presumably makes McCreadie look like the ugliest character in his own fawning narrative, especially since it unfortunately climaxes with McCreadie’s disastrous 60th birthday party, an expensive toga-party-themed ‘do that’s attended by musicians, celebrity impersonators, and a real-life lion.

Still: for some reason, Nick’s crisis of conscience takes a while to occur, despite the fact that McCreadie is very proud to have made his fortune by lowballing everybody from sweatshop owners to clothing distributors. McCreadie may not be a real person, but he is apparently evil: he skates by knowing that his money talks much louder than any governmental regulation could (as he argues in a deposition where he points out that most large corporations don’t pay taxes).

It’s easy (and fun) to hate McCreadie since Coogan’s become adept at parodying this type of oafish, Barnumesque personality. But Mitchell’s character is even uglier: Nick’s such a patsy that he, in addition to conducting interviews for McCreadie’s book, also records awkward birthday messages for McCreadie’s birthday party, including a salute from the Sri Lankan sweatshop workers that McCreadie employs. Mitchell’s also very good at playing this kind of spineless loser (see: “Peep Show”), so it’s hard to dismiss his character as just a hateful parody of what the fourth estate has become after being bought up by Murdoch-style McMoguls. There’s also a lot of truth to most scenes where Nick puffs out his chest with a scholarly but inexact quip (he paraphrases Shakespeare and Shelley, but doesn’t seem to have read any). Still, it’s hard to laugh (or just nod grimly) whenever Nick, a walking one-note joke, acts like a wide-eyed mouth-breather whenever he hears McCreadie’s former associates tell on Nick’s scuzzy employer.

Winterbottom also doesn’t make full use of his main hook, namely that “Greed” is a satire whose style—a dramatic Great Man narrative, full of tastefully lit, wide-angle master shots—is at odds with the funny/sad findings of Nick’s investigations. So why is Nick even in “Greed”? He only seems to exist so that Winterbottom can get in a few good (and several ineffectual) digs at the media that he understandably considers to be complicit in Green’s well-publicized extra-legal activities.

Thankfully, Coogan’s characteristically scene-stealing performance is already nuanced and funny enough to land most of Winterbottom’s bold-faced talking points. See Coogan dismiss a group of inconveniently located Syrian refugees (they’re too close to McCreadie’s party) with a wave of his hand and some uncomfortable stammering: “They’re refugees! They can find refuge … somewhere … ” Watch McCreadie airily dismiss a Rod Stewart lookalike as Stewart’s “bitter brother.” Marvel as Coogan makes you believe that a rich dolt like McCreadie could be so blinded by his own self-regard that, when his son (Johnny Sweet) quotes “Gladiator” while acting out, McCreadie can only think to say: “I didn’t teach him that. I don’t even think that’s in the film … ” But even Coogan can’t save material as leaden as McCreadie’s concluding soliloquy, a self-deflating monologue whose impact is soon undercut by a pre-credits, Powerpoint-style presentation on the real-life corporate greed that McCreadie represents.

The makers of “Greed” rarely get out of their own way long enough to let their movie’s acrid sense of humor speak for itself. The film’s tone and narrative focus are all over the place, which is a shame, because most of the movie’s contributors are good enough to be great on their own, and even better together. But the makers of “Greed” never manage to top the moment when, after McCreadie’s party inevitably blows up, a soon-to-be-ex-employee (Pearl Mackie) rushes to save herself by pushing aside a Keith Richards impersonator: “F**k off, Keith!” The rest of the movie is frequently clever and true, but rarely smart enough to resonate beyond its biggest laughs.