Lushly photographed and grandly conceived, Carlos Saura’s “Goya in Bordeaux” never comes alive. It is an homage to the great Spanish painter, but we must come to the film already fascinated by Francisco de Goya; if we do not, the film will not convince us. It is too much a study and an exercise, not enough a living thing.

The film opens with an extraordinary image: a cow’s carcass, dragging itself to a scaffold and then hoisted up so that we can regard animal flesh and meditate that thus are we all. Then the details of muscle and fat begin to run like paint, until they reveal the ruined face of an old man. This is Goya on his deathbed.

The old man rises up, confused. Where is he? Who bought him here? He wanders from his bed, and a shift in the lighting reveals the walls of his room as a scrim. We can see him through the walls, and then find him wandering bewildered in the street, until he is found and taken home by his daughter Rosario. For the rest of the film he will relate his memories to Rosario, and we will see many of them in flashback, as well as his nightmares and fantasies.

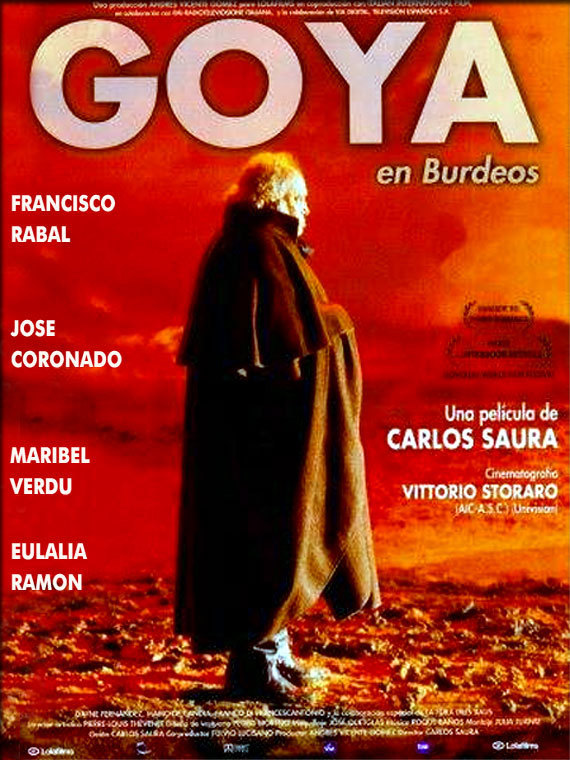

The cinematographer is Vittorio Storaro, who has worked with Saura frequently. “Tango” (1999) is a recent collaboration, the story of a man trying to make a film in Argentina, caught in a labyrinth of love, politics and music. “Goya in Bordeaux” is as good looking but not as fruitful.

Goya has fled to France, we gather, because of troubles at home, linked to the fate of the woman of his dreams, Cayetano, Duchess of Alba (Maribel Verdu). She unwisely opposed Queen Maria Luisa and paid with her life; now Goya, in exile, likes the scenery and the wine but misses his villa in Madrid.

As Rosario sits by his side, her attention sometimes drifting (as ours does), Goya recalls his earlier years, his experiments with paint and lighting, the illness that made him deaf. Played as an old man by Francisco Rabal and in middle age by Jose Coronado, he finds it difficult to draw a line between his work and his life. Cayetano emerges from a painting to cast a shadow over him, one that eventually will mark his life’s end. Other death’s-head specters also emerge from his canvases, or his memories of them, to haunt his dreams.

There are better films about how a painter works (Rivette’s “La Belle Noiseuse” from 1991 is incomparable), and better films about old men remembering their lives. Goya, younger and older, shuffles through morose regrets and rueful memories. He does not seem to have created his paintings so much as become their innocent victim. This is not a stand-alone film so much as a visual aid to the study of Goya; I could imagine an old 16mm projector clacking away in the back of art appreciation class.