It is all so sordid. “Gomorrah” is a film about Italian criminals killing one another. One death after another. Remorseless. Strictly business. The question arises: How are there enough survivors to carry on the business? Another question: Why do willing recruits submit themselves to this dismal regime?

The film is a curative for the romanticism of “The Godfather” and “Scarface.” The characters are the foot soldiers of the Camorra, the crime syndicate based in Naples that is larger than the Mafia but less known. Its revenues in one year are said to be as much as $250 billion — five times as much as Bernard Madoff took years to steal. The final shot suggests that the Camorra is invested in the rebuilding of the World Trade Center. The film is based on fact, not fiction.

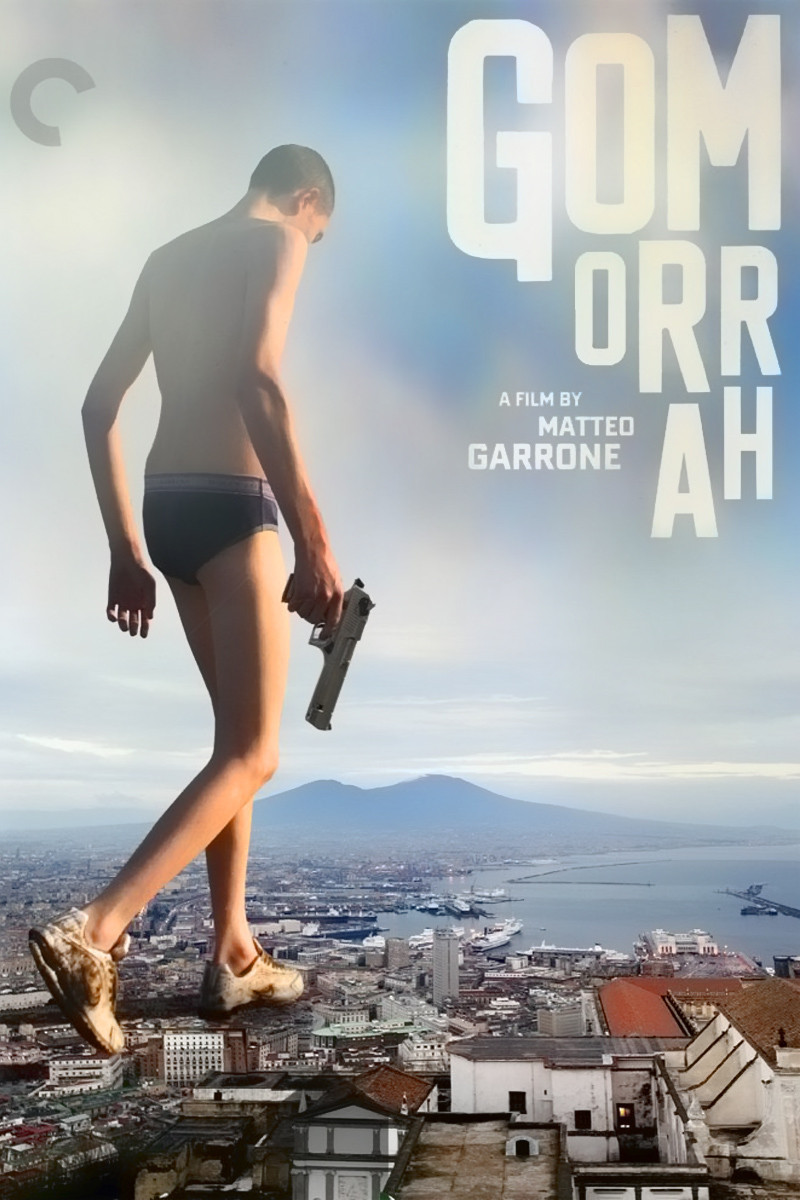

“Gomorrah,” which won the grand prize at Cannes 2008 and the European Film Award, is an enormous hit in Europe. It sold 500,000 tickets in France, which at $10 a pop makes it a blockbuster. There was astonishment that the Academy Awards passed it over for foreign film consideration. I’m not so surprised. The academy more often goes for films that look good and provide people we can care about. “Gomorrah” looks grimy and sullen, and has no heroes, only victims.

That is its power. Here is a film about the day laborers of crime. Somewhere above them are the creatures of the $250 billion, so rich, so grand, so distant, with no apparent connection to crime. No doubt New York and federal officials sat down to cordial meals with Camorra members while deciding the World Trade contracts, and were none the wiser.

Roberto Saviano, who wrote the best seller that inspired the movie, went undercover, used informants, even (I learn from John Powers on NPR) worked as a waiter at their weddings. His book named names and explained exactly how the Camorra operates. Now he lives under 24-hour guard, although as the Roman poet Juvenal asked, “Who will guard the guards?”

Matteo Garrone, the director, films in the cheerless housing projects around Naples. “See Naples and die” seems to be the inheritance of children born here. We follow five strands of the many that Saviano unraveled in his book, unread by me. There is an illegal business in the disposal of poisonous waste. A fashion industry that knocks off designer lines and works from sweatshops. Drugs, of course. And then we meet teenagers who think they’re tough and dream of taking over locally from the Camorra. And kids who want to be gangsters when they grow up.

None of these characters ever refer to “The Godfather.” The teenagers know De Palma’s “Scarface” by heart. Living a life of luxury, surrounded by drugs and women, is perhaps a bargain they are willing to make even if it costs their lives. The problem is that only death is guaranteed. No one in this movie at any time enjoys any luxury. One of them, who delivers stipends to the families of dead or jailed Camorra members, doesn’t even have a car and uses a bicycle. The families moan that they can’t make ends meet, just like Social Security beneficiaries.

Garrone uses an unadorned documentary style, lean, efficient, no shots for effect. He establishes characters, shows their plans and problems, shows why they must kill or be killed — often, be killed because of killing. Much is said about trust and respect, but little is seen of either. The murders, for the most part, have no excitement and certainly no glamor — none of the flash of most gangster movies. Sometimes they’re enlivened by surprise, but it is the audience that’s surprised, not the victims, who often never know what hit them.

The actors are skilled at not being “good actors,” if you know what I mean. There is no sizzle. Only the young characters have much life in them. Garrone directs them to reflect the bleak reality of their lives, the need and fear, the knowledge that every conversation could be with their eventual killer or victim. Casual friendship is a luxury. Families hold them hostage to their jobs. The film’s flat realism is correct for this material.

You watch with growing dread. This is no life to lead. You have the feeling the men at the top got there laterally, not through climbing the ladder of promotion. The Camorra seems like a form of slavery, with the overlords inheriting their workers. The murder code and its enforcement keep them in line: They enforce their own servitude.

Did the book and the movie change things? Not much, I gather. The film offers no hope. I like gangster movies. “The Godfather” is one of the most popular movies ever made — most beloved, even. I like them as movies, not as history. We can see here they’re fantasies. I’m reminded of mob bosses like Frank Costello walking into Toots Shor’s restaurant in that fascinating documentary “Toots.” Everyone was happy to see him: Jackie Gleason, Joe DiMaggio, everyone. At least they knew who he was. The men running the Camorra are unknown even to those who die for them.