Near the beginning of “Girls Town” there is a scene where two high school girls have a heart-to-heart talk while sprawled on a bed, reading a journal. It’s one of those moments when the whole future seems filled with promise, even if the destinies are different: Emma (Anna Grace) and Nikki (Aunjanue Ellis) talk about their school plans, and Emma is quietly surprised that Nikki, who is going to Princeton, still hasn’t signed up for housing.

The next day Nikki’s delay is easier to comprehend. She has committed suicide. Her closest friends cannot understand, and during a visit to Nikki’s home, they steal her journal and read it for themselves, discovering that Nikki was raped while working as an intern at a local magazine.

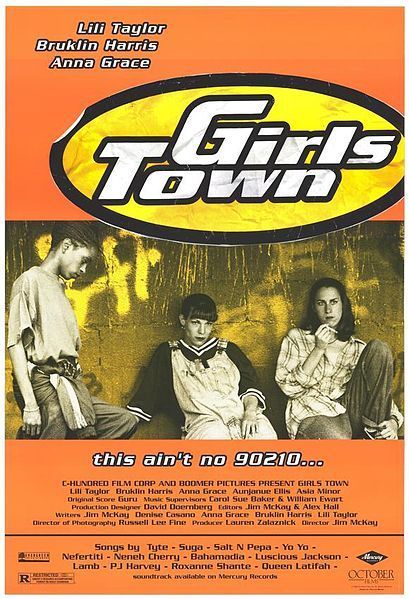

This information simmers beneath the surface of “Girls Town” as we learn more about Nikki’s three friends, who are Patti (Lili Taylor), Angela (Bruklin Harris) and Emma. They are tough but not hardened, self-defined outsiders with a strong feminist code they don’t talk much about. Their racial balance (two whites, two African Americans) shows their willingness to stand outside the cliques of high school and choose their friends instead of letting teenage society dictate to them. Angela and Emma are headed for college; Patti, a single mother, “has been let back so many times that what is she now? Forty?” During the film, the young women will talk a lot, in conversations that sound natural and unforced; I understand the screenplay was developed partly through improvisations by the actors. They realize they never really knew Nikki, even though they thought she was their best friend, and they reveal their own secrets. Emma reveals that she has also been raped. Patti, who has a shaky relationship with Eddie, the loser father of her child, observes, “They wanna have sex with you, you don’t want to have sex with them, they gonna get it. You call that rape, I been raped by about every guy I been out with.” The girls paint a mural in Nikki’s memory, and while it provides some consolation, it is finally not enough. Gradually, fueled by the logic of their conversations, many of which take place on the roof of the dugout on the school’s baseball field, the three decide on more direct measures. They vandalize the car of the classmate who raped Emma, and then they decide to go after the smug and uncaring older man who raped Nikki.

The bare bones of the plot of “Girls Town” are not much more subtle than the events in a 1970s exploitation picture like the recently (and unnecessarily) revived “Switchblade Sisters.” But nuance is everything, and the movie’s qualities are in the performances and dialogue. We hear the convincing sound of smart teenage girls uncomfortably trying to discover and share the truth about themselves, and we sense the social structure of the school in scenes (usually in the women’s washroom) where the three confront their “popular” classmates.

In every high school there are always “popular” students and various groups of outsiders. It is always thought better to be “popular.” One of the lessons of “Girls Town” is that popularity is based on the opinion of others, while an outsider chooses that status on the basis of her opinion of herself. We see Patti, Emma and Angela behaving unwisely and recklessly in “Girls Town,” but we also see them growing, and trying themselves, and discovering who they are. It is a painful process–so painful, many people never do it. I would like to see another movie in three or four years, about what has happened to these angry, gifted friends.