“Got up went to Twickenham rehearsed until lunchtime — left the Beatles — went home, and in the evening did King of Fuh at Trident studio, had chips later.” So George wrote in his diary on Jan. 10, 1969. He returned a few weeks later, and then the band broke up for good after January, 1970.

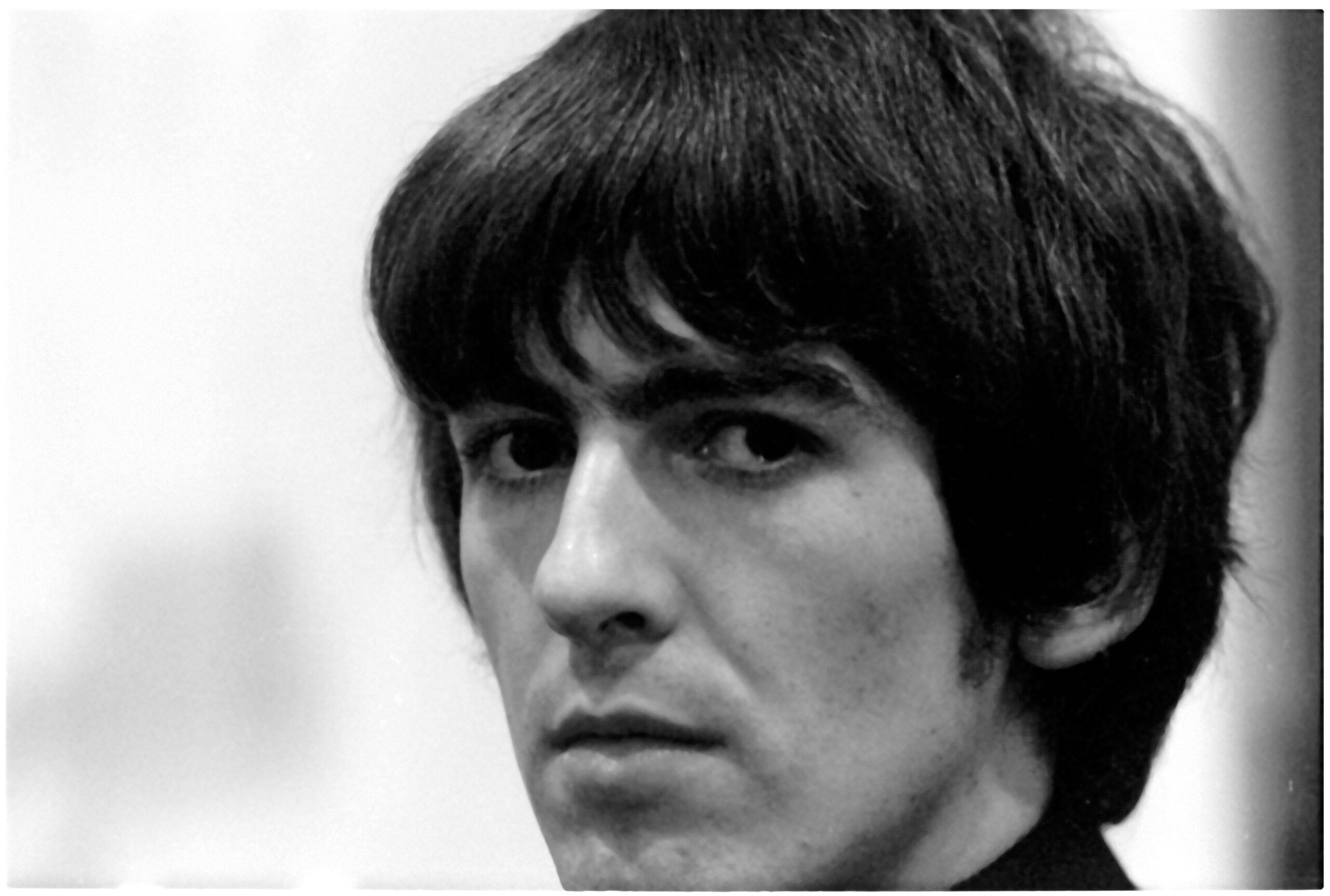

George Harrison always seemed to me the unhappiest of the Beatles. Of course such an opinion is worthless. The Beatles are a screen upon which we project our own ideas, and George seemed the least willing to be projected upon. To be a member of that group, to have a hand in creating the pop music of our time most likely to be heard in later centuries, was to run the risk of losing yourself. George (we call them all by their first names) was the most defiantly individual.

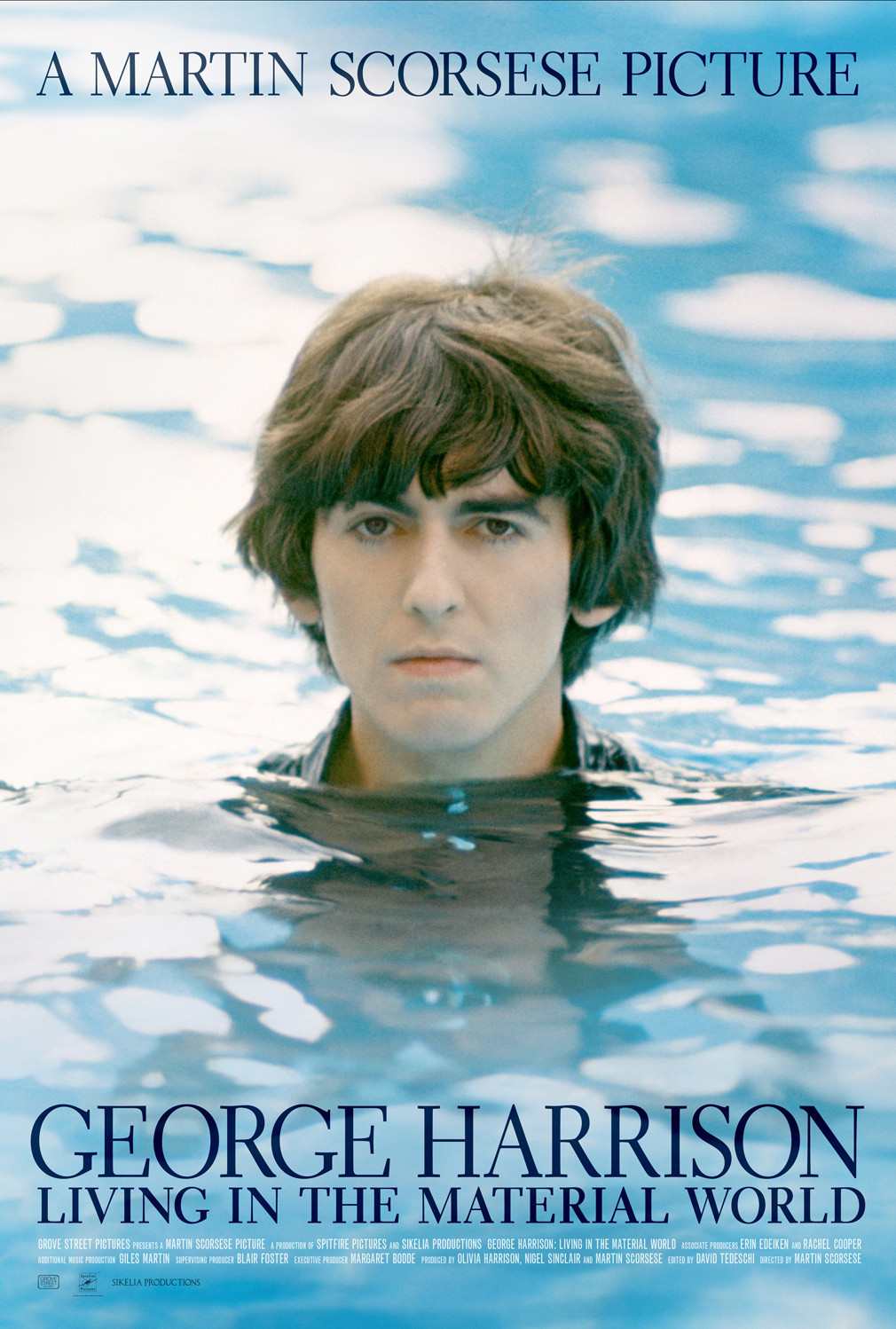

In Martin Scorsese’s documentary “George Harrison: Living in the Material World,” Harrison’s journey is traced as a search for himself in the tumult of incoming distractions. It is clear, as Paul Theroux points out in a recent article, that in Harrison’s life Scorsese saw much of his own reflected. They began as lonely, alienated children. They found escape and joy in music and film. They focused their lives on those arts. They resisted the possibility of being entirely consumed.

This is a long film, for which the expansiveness of cable television is appropriate. With “Material World,” which will debut over two nights on HBO, at 208 minutes, Scorsese has accomplished the best documentary that is probably possible. With George’s faithful second wife, Olivia, as his co-producer, he has assembled all the archival material, all the photos, all the film and video, transient and lasting.

With his own prestige, and because they loved George, Scorsese has been able to call on those who knew Harrison in all weathers: his son Dhani, Ringo and Paul, Yoko Ono, Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam, Eric Clapton, Jackie Stewart and many others.

“In my beginning is my end,” T.S. Eliot wrote. For George Harrison, raised in the working class in postwar Liverpool, one of those beginnings must have been his father’s vegetable garden. Victory Gardens, they were called during and after the war, and my own father had one, too. All through his life, as money and fame came to him, he found pleasure seeking houses with gardens.

English country houses are known for their gardens, but many of their owners never got their hands dirty. George was obsessed by the physical act of gardening, working with his land every day that he could. When you garden, you imagine its effect for those who will see your garden — for future generations and strangers. It is a gift you give to the land and to others, and it shows love of beauty in a pure form.

George’s professional life was caught up in a maelstrom almost from the day he first auditioned for John and Paul, playing “Raunchy” for them on the top deck of a bus. Scorsese’s film deals fully with the rise of the Beatles, when pop stardom was transformed into a great deal more, because it quickly became obvious that the Beatles were extraordinary.

Paul and John were the composers of most of the great Beatles hits. George wrote hundreds of songs, but somehow they kept being squeezed out of albums and not included on show lists. There is an invaluable scene here showing him in an argument with Paul. His songs were not valued as he thought it should be, and after he struck out on his own, we heard much more of his work.

Searching for inner quiet in the chaos of stardom, he found himself drawn to Eastern religion, and was instrumental in bringing the Beatles under the influence of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. He joined the Hare Krishna tradition and was a vegetarian from 1968 until he died.

George believed that a great purpose of life was to prepare oneself for death. With chanting and meditation, he turned inward. His serenity received a severe challenge when he and his wife were attacked by an invader in his home, and he was stabbed as they fought off the mentally disturbed man.

Thoughts of the murder of John Lennon must have struck him with great force. In 1997, he was diagnosed with throat cancer, which later spread to his lungs and his brain. He died in 2001.

All of this, and a great deal more, is covered in this respectful film. This is a more objective, less personal documentary than Scorsese usually makes. Considering its length, there isn’t much concert footage, and it focuses on archival interviews with George, news footage, and an impressive selection of talking heads.

Those who knew George loved and respected him. His use of LSD and other drugs is discussed, but he seems to have been seeking truth, not a high, and soon enough he was drug free and found his highs in spiritual practices. He left his music. Even now, there is something a little hidden and private about him. I suspect if we want to sense his presense, we should visit his gardens.