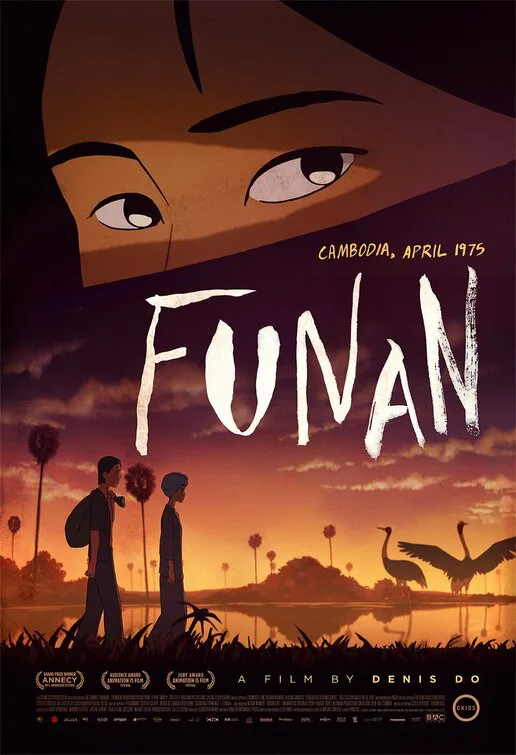

Dennis Do’s powerful animated drama “Funan” chronicles one family’s attempts to survive the Khmer Rouge regime, which took over Cambodia in 1975 and plunged the country into deprivation, suffering, and genocide. In addition to being a rigorously written and directed personal account of a specific war, the film is an illustration of animation’s possibilities for artistic expression, which have recently been choked off in the international cinema marketplace by the success of basically lighthearted, Pixar-styled, “fun for the whole family” movies, and to a lesser extent, certain flavors of anime.

This is something different—an epic historical drama of a kind that would be submitted for all sorts of Oscars if it were live-action, with realistic sound design and panoramic widescreen images composed as if the camera had been pointed at people and things that exist. It deserves favorable comparison with such films as “Persepolis” and “Waltz with Bashir,” although it’s more straightforward in its style, and suffers from being too brief and fragmented, and a bit flat in its characterizations, at least compared to the power of its images and sounds.

The story begins in 1975 with the fall of Phnon Penh to the Khmer Rouge, a Communist organization allied with the North Vietnamese and Chinese whose power accumulated as a result of the American bombing of civilians during the war. The takeover of the city drives a middle-class family, headed by Chou (Bérénice Bejo) and her husband, Khuon (Louis Garrel), onto a forced march that separates them from their four-year old son and his grandmother. A minor official of the ascendant government assures the parents that their child has simply been relocated, and is safe and under careful supervision, even though we know that this cannot possibly be true. The boy’s absent presence is at once a continual source of fear and unhappiness and a beacon of hope. At many points during the story, it is only the faint possibility of reuniting the extended family that prevents its members from letting themselves die of starvation or despair, or prematurely end things by their own hand.

“Funan” is structured as a series of carefully choreographed set pieces in which things go from bad to worse to unimaginably awful. The parade of horrors starts with the forced evacuation of the city and the subsequent torching of the family’s car by a couple of soldiers who declare them decadent enemies of the revolution and escalates from there. By the midpoint, the remains of the now-splintered family are imprisoned in one of countless, incompetently managed work farms that sprung up across the country in the late 1970s, as a result of the Khmer Rouge attempting to remake the entire economy as a centrally organized producer of agricultural goods, powered by slave labor and controlled by party hacks and armed, often illiterate goons.

War movies aren’t known for their lightheartedness, and this one is no stroll in the park. There are beatings, tortures, executions, implied sexual exploitation, and other wartime atrocities. The material is so dire, in fact, that were it not for the inspirational through-line of family members doing whatever has to be done to save each other, as well as Do’s restrained direction, the experience might have been unbearable.

For the most part, “Funan” keeps gruesomeness offscreen and focuses on the reaction of witnesses. This prevents the movie from turning into a voyeuristic display of cruelty or a masochistic wallow in pain. The director might, say, cut from an impending execution-by-rifle to a closeup of a nearby witness just in time to catch a muzzle flash lighting up their face, or reveal a suicide victim by following behind the shoulders of the person who discovers the body, then cutting to reveal the dead person’s legs. It’s “You get the idea” filmmaking that connects “Funan” with an older tradition of historical epic, and makes it at least theoretically possible for the project to connect with a wider audience.

A sense of long-deferred righteous anger powers the middle part of the movie. Do, who is of Cambodian ancestry but grew up in France, based the screenplay partly on the experiences of his mother, who survived a similar experience while being separated from Do’s older brother, and finally escaped the country in 1979. This is a story that has been told before in bits and pieces, often through Western eyes (see “The Killing Fields” and “First They Killed My Father”), and never before in such an inherently stylized format.

The relative brevity of the movie, coupled with its being structured around trauma rather than character development, and its relative flatness as a political history, prevents it from reaching its full potential as either memoir or expressive art. But the direction, sound design, and music (by Thibault Kientz-Agyeman) are enough to lend the project a unifying hypnotic energy that helps it overcome its shortcomings.

The tendency of some modern viewers to assume that all cartoons should be kid-friendly will surely inspire outraged comments by folks who failed to read up on “Funan” before seeing it. But those who go into the picture with clear eyes and focused minds will appreciate the singularity of what Do has achieved here.