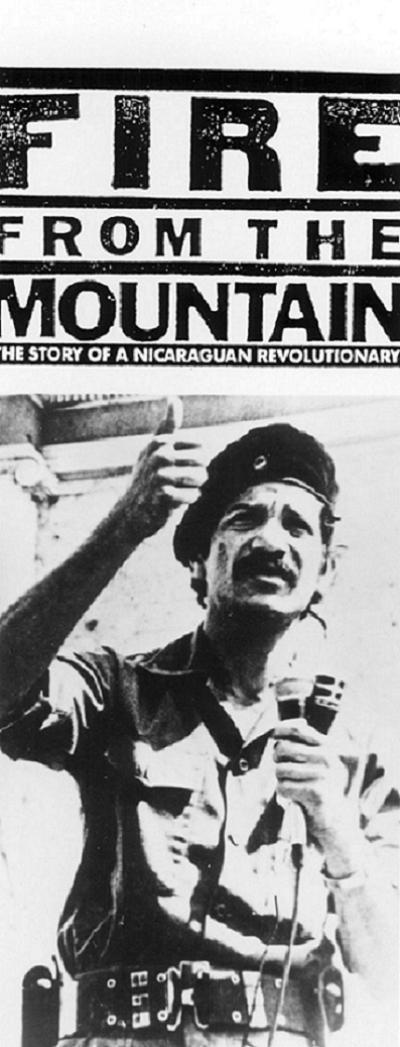

The story is based, loosely, on the autobiographical book by Omar Cabezas, a Nicaraguan poet, revolutionary and now Sandinista cabinet member. He is seen in current footage and also in archival film as he led rebellious students at his university and then cast his lot with the Sandinista uprising against the Somoza government. As he talks in the background in Spanish, his words are overdubbed in English, and there is no doubt he is an evocative spokesman.

We learn of the long history of American interference in his country and the way the United States propped up the corrupt Somoza regime while the ordinary people lived in poverty. We learn of the handful of Sandinistas who formed a cadre in the mountains and of how their revolution eventually grew to sweep away the Somozan government, only to be opposed by the U.S.-backed Contras. The film ends in a lament: Nicaragua would be free to get on with the job of rebuilding if only the Contras were not attacking and destroying the villages of peace-loving Sandinista peasants.

This is one version of events in Nicaragua, and probably a more accurate one than the version supplied by the Contras’ backers in Congress. But it is only a version of the truth. As the film lamented about the Contra attacks on innocent villagers, I was reminded of a far more honest, far more uncompromising 1985 documentary named “Ballad of the Little Soldier,” by the great West German director Werner Herzog.

His film does not merely speak of pillaged villages, but shows them.

And they have been destroyed, not by the Contras, but by Sandinista troops.

Herzog went to Nicaragua as a supporter of the Sandinistas, but he was a reporter, not a propagandist, and when he found a compelling story, he filmed it. His documentary is about the Miskito Indians, who fought against the Somoza regime and then looked forward to joining the Sandinistas. This was not to happen. According to Herzog, the Sandinistas uprooted the Miskitos from their villages, forcibly resettled them, burned their homes and crops, slaughtered their cattle and killed those who opposed them.

Herzog tells both sides of a complicated story. The Miskitos then turned against the Sandinistas, accepted aid from the CIA, declared their own war on their erstwhile allies and (in Herzog’s most harrowing footage) fielded a guerrilla army including soldiers as young as 10.

The tangled web of the Miskitos demonstrates how hard it is to report objectively on Nicaragua. “Fire from the Mountain” doesn’t even try. Anyone with a fair knowledge of archival film resources and film editing techniques will be able to spot several places in the film where we are probably not being shown what we are told we are being shown. During Cabezas’ long, impassioned monologue about his slog through the mud up the mountainside, for example, are we to believe that the shots of muddy boots were taken at the time? When the film speaks of American planes bombing Nicaragua, we see a far-away plume of smoke, and then obviously unrelated footage of a single lonely propeller plane flying somewhere. Is it the same plane that dropped the bombs? Other parts of the film are simply ineptly made. What conclusion are we to draw, for example, after a long passage in which the narration complains of how hot it was in a certain Easter week? Cabezas goes on and on about the heat, about how nobody could move, about how the sun beat down. So what? Did the Yankees make it hot? Is it cooler under the Sandinistas? What does the climate have to do with the revolution? The film is only spinning its wheels.

Much is made in the current comedy “Broadcast News” about the heroine’s inability to recognize that the footage is faked when the anchorman cries on camera. I doubted at the time that any experienced news producer would have fallen for the tears in the first place.

Anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of filmmaking would likewise be made very uncomfortable by “Fire from the Mountain,” which has its primary loyalty to the Sandinista myth, not to ideas of objectivity and honesty.