In 1972, Amil Dinsio and his bank robber crew broke into the United California Bank in Laguna Nagel (a long way from Youngstown, Ohio, where the burglars originated) and stole an estimated $9 million, the biggest bank heist in U.S. history up until that time. One of the distinguishing characteristics of this particular heist was the burglars’ sophisticated knowledge of explosives and different alarm systems. They got into the bank through a dynamite blast in the roof. The crew was eventually busted, and have remained folk heroes of a sort. The plan was to steal the “dirty money” donated by all sorts of unsavory people to President Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign, and stashed in a safe deposit box in the bank by Charles Colson, Special Counsel to the President (and future federal prison inmate for his role in the Watergate scandal). Their heist didn’t really work out as planned, but the intent behind it is what makes it all so interesting. Dinsio and his guys figured: the money was so dirty it deserved to be stolen. Mark Steven Johnson’s “Finding Steve McQueen,” with a script by Ken Hixon and Keith Sharon, is a light comedic “take” on these events, all seen through the eyes of Harry Barber, the guy who drove the getaway car, a guy whose idol is Steve McQueen.

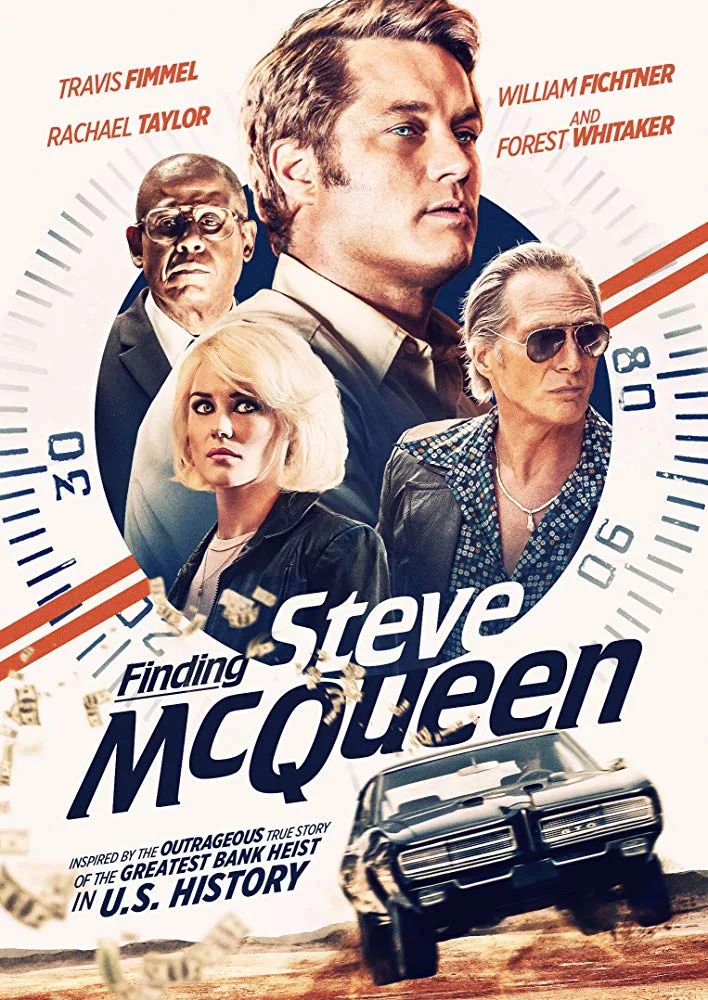

“Finding Steve McQueen” starts in 1980, when Barber (Travis Fimmel), a stammering good-natured hunk with bright blue eyes, comes clean to his girlfriend Molly Murphy (Rachael Taylor) about his real identity after seeing his face on an FBI Most Wanted poster. He’s been on the lam for 8 years after robbing a bank in 1972, and he’s been operating under an assumed name ever since. The two sit in a diner, and he tells his story, launching the narrative back to 1972 when it all began.

The heist movie has a long pedigree, and while “Finding Steve McQueen” is no “Le Cercle Rouge” or “Rififi” (or even “Reservoir Dogs“), Johnson keeps the tone light, vivacious, almost slapstick at times. This is a smart choice. The movie could have taken itself very seriously, bogging itself down in political commentary. Instead, there’s a loose vibe, and some humor in the culture clash of roughneck Ohio guys circulating in anything-goes California, gobsmacked by the hot tubs and hot chicks. Enzo (William Fichtner) is the mastermind, sleazy and smart, and so angry about Vietnam his rage quivers through his body when he talks about it. Enzo loops his nephew Harry into the scheme since Harry is known to be hell on wheels (the real Harry Barber apparently got 41 speeding tickets in one year). Harry drives a 1969 Mustang GTO, modeling himself after Steve McQueen in “Bullitt” (although Bullitt drove a 1968 Ford Mustang). At one point, Harry is seen in a pose mirroring Steve McQueen’s in the famous “Bullitt” poster.

Opposite all this activity is the FBI investigation, led by agents Howard Lambert (Forest Whitaker), and Sharon Price (Lily Rabe). Two pioneers in their field, he as an African-American, she as a woman, they both have a desire to prove themselves, and there are all these weird mournful layers to their interactions (his marriage is in trouble, she seems to have a crush on him). This is an eccentric choice, but it works. (“Finding Steve McQueen” works best when it embraces eccentricity.) Whitaker and Rabe create a believable vibe of two melancholy loner workaholics, bonding together, treating each other with care as they try to solve the case.

The pop culture talk among the thieves is stifling, each reference like an arrow pointing to the year, as though everyone in 1972 sat around talking about Sally Struthers, Mod Squad and Richard Bach 24/7. The music falls into a similar Greatest Hits of 1972 trap. There’s one car chase early on in “Finding Steve McQueen”, when Harry flees from a police car through a quarry, and except for a couple of graceful overhead shots, the scene points up how car-chase execution in film is practically a lost art. This wouldn’t matter so much except that “Bullitt” is still known for its awe-inspiring car chases, and Harry is such a gearhead, we want to see more of it.

Steve McQueen’s star remains bright, and the influence of his parade of charismatic loners can still be felt. McQueen worked steadily in television in the 1950s, before ushering in the 1960s with the mega-hit “The Magnificent Seven,” surrounded by an all-star cast made up of old Hollywood types and young Method actors. He was a “bridge” figure, straddling the old-school style with the new Actors Studio ethos. McQueen was a movie star who sometimes operated on sheer charisma alone. His solitary escape from the German prison camp in “The Great Escape” (everyone else breaks out in a group, but not Hilts!) is pure Hollywood, a meta-moment of myth-making, with McQueen as hero and anti-hero, roaring across the fields on his motorcycle, that symbol of 1950s rebellion. As the 60s heated up, ideas of masculinity fractured, and McQueen called up an earlier time, yet still iced over with the new “cool” of the 1950s. It’s hard to believe he was only 50 years old when he died.

“Finding Steve McQueen” could have used more of the galvanizing spirit of its patron saint, but there’s also much to recommend here, in particular its light-hearted energy. It’s fun to revel in the audacity of what these guys almost pulled off.