If you were watching the 1993 Academy Awards telecast, you saw Federico Fellini at his effortless best, taking center stage and handling the crowd with more poise, humor and authority than any of the highpriced stars who surrounded him.

He invited the audience to relax. He professed surprise at being honored – and then confessed he was not surprised at all. He commanded his wife, Giulietta Masina, to stop crying – at once! Watching him, you received an overwhelming impression of a man who felt thoroughly comfortable with himself.

That is the impression Fellini always gives, like an orchestra conductor who knows the music and trusts his players. And that is one of the reasons his 1963 masterpiece, “8 1/2,” is such an unlikely film, since it pretends to be autobiographical and yet shows us a movie director who is emotionally frayed and artistically bankrupt.

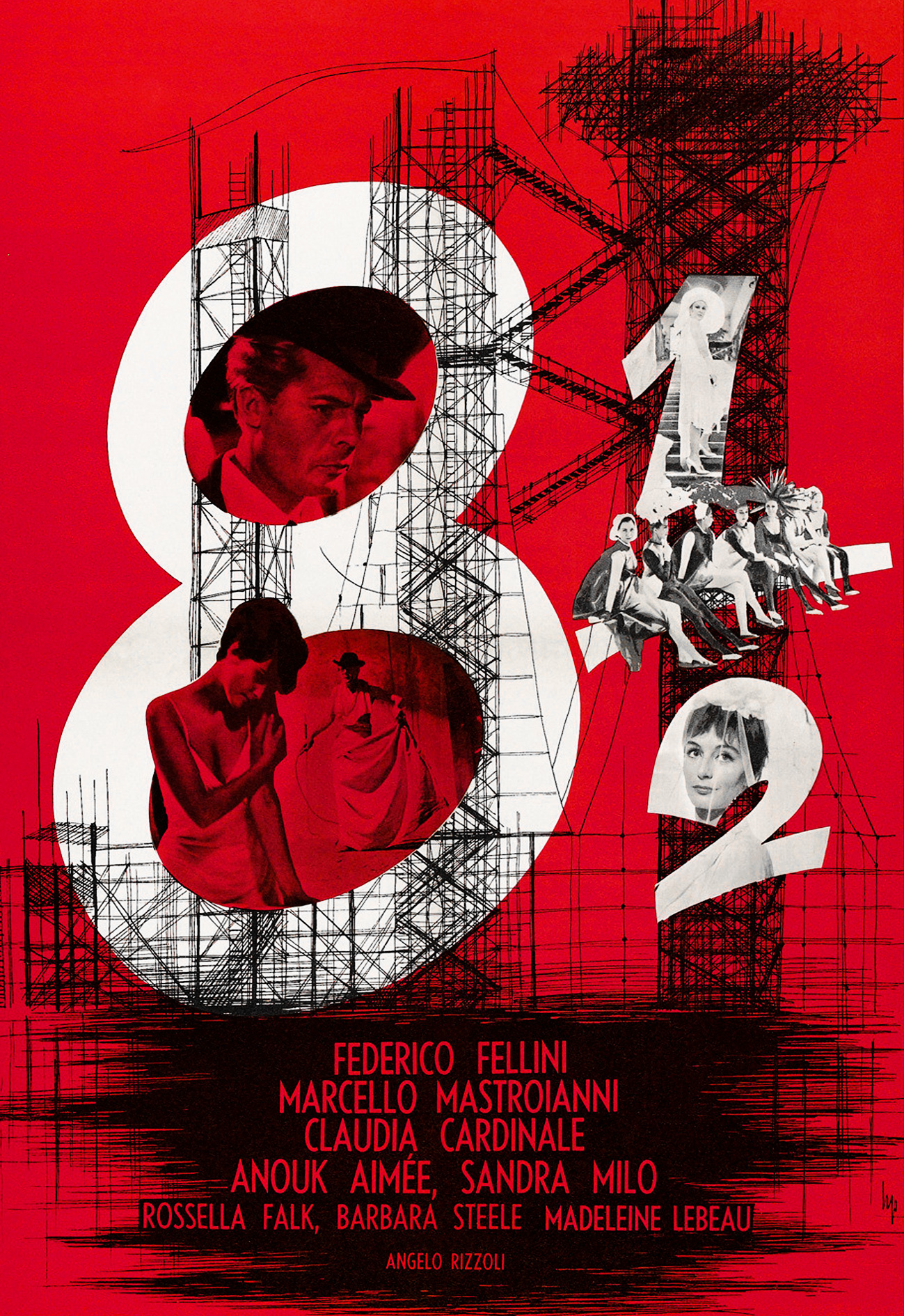

The movie is currently being revived around the country with a new 35-mm print in glorious black and white. It’s out on video, but it’s so big and rich it deserves to be seen on the big screen, and this 30th anniversary revival may be your last chance for a long time. “8 1/2” routinely places high on those polls that ask critics and directors to list the 10 greatest films of all time.

Fellini directed it on the rebound from the enormous international success of “La Dolce Vita” (1961), which made both him and Marcello Mastroianni famous. “La Dolce Vita” remains, for my money, the best of Fellini’s films; it’s a sad, shocking, exuberant portrait of a Roman gossip columnist having a crisis of the spirit.

But “8 1/2” is a great film in its own way, and despite the efforts of several other filmmakers to make their own versions of the same story, it remains the definitive film about director’s block.

The movie stars Mastroianni, always Fellini’s alter ego, as Guido, a director who has had a big hit and now seeks to recover from it at a health spa. But he is hounded there and everywhere by those who depend on him – his producer, his writer, his mistress, his would-be stars. The producer has spent a fortune to build a gigantic set of a rocket ship, but Guido has a secret: He doesn’t have a clue what his next movie will be about.

The movie proceeds as a series of encounters between Guido and his conscience. He remembers his childhood, his strict parents, his youthful fascination with a tawdry woman who lived down by the beach.

His mistress (Sandra Milo) follows him to the spa, and then his chain-smoking, intellectual wife (Anouk Aimee) follows, and is enraged at him – as much for his bad taste in women as for his infidelity.

Then follows one of the most famous sequences in all of modern films: In his daydreams, Guido occupies a house with all of the women in his life, past and present, and they all love him and forgive him, and love one another. But then there is a revolt, and he cracks a whip, trying to tame them. Of course he cannot.

The movie is the portrait of a man desperately trying to weld together the carnal and spiritual sides of his nature; the mistress and the wife, the artistic and the commercial. From time to time a muse appears to him: a seductive, calm, smiling dream woman (Claudia Cardinale). She offers him the tantalizing possibility that all will be forgiven, and all will be well. But she is elusive and ethereal, and meanwhile the producer is growing desperate.

All of Fellini’s movies contain his trademarks, such as constructions that stand between the earth and the sky, and parades in which the characters proceed like circus performers. This film gives us the rocket set, a tower to nowhere, and ends at dusk with a sad circus parade, the clowns leading all of the people in Guido’s life around and around in circles.

Thirty years after Fellini made “8 1/2,” films like this have grown rare. Audiences demand that their movies, like fast food, be served up hot and now. The self-indulgence and utter self-absorption of Fellini, two of the film’s charms, would be vetoed by modern financial backers. They’d demand a more commercial genre piece.

These days, directors don’t worry about how to repeat their last hit, because they know exactly how to do it: Remake the same commercial formulas. A movie like this is like a splash of cold water in the face, a reminder that the movies really can shake us up, if they want to. Ironic, that Fellini’s film is about artistic bankruptcy seems richer in invention than almost anything else around.