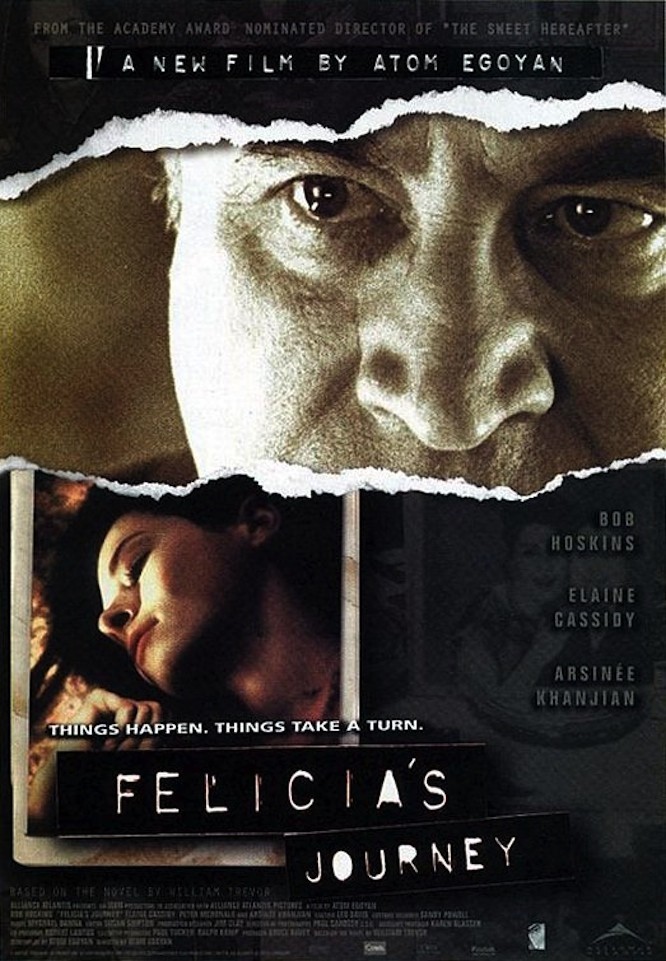

Atom Egoyan‘s “Felicia’s Journey” tells the story of two children escaping from their parents. One of the children is middle aged now, an executive chef for a factory lunchroom. The other is an Irish girl, in England to seek the boy who said he would write her every day and then never wrote at all. It is their misfortune that the paths of these two children cross.

The man is named Hilditch. He is played by Bob Hoskins, that sturdy, redoubtable fireplug. At work his staff is in thrall to his verdict. He sips a soup and disapproves: “It starts with the stock!” He lives alone in a huge house where nothing seems to have changed since the 1950s. He spends his evenings cooking ambitious dinners like a saddle of lamb and eating them all by himself, listening to Mantovani on a record player. His drives a Morris Mini-Minor, a bulbous little car designed along the same lines as its driver.

The girl is named Felicia (Elaine Cassidy). She is sweet and bewildered. She gave her love to Johnny (Peter McDonald), who left for England–to work in a lawn mower factory, he said. She is pregnant. Johnny has not written. Her father (Gerard McSorley) is a rabid Irish nationalist who is convinced Johnny has gone to join the British army. He is offended by his daughter’s pregnancy not on moral but political grounds: “You are carrying the enemy within you!” Felicia takes the ferry to England and goes looking for Johnny’s lawn mower factory. Kindly Mr. Hilditch sees her wandering the streets and offers her guidance, and even a ride to a nearby town where Johnny might be working. Hilditch explains that his wife is a patient in the hospital there. We slowly gather that Mr. Hilditch is not a nice man, that he has no wife, that Felicia is in some kind of danger. The look of the film, wet, green, brown, cool, dark, underlines the danger.

The key to “Felicia’s Journey” is that it has understanding for both characters–for Felicia, who is innocent, and for Hilditch, who is the product of a childhood which turned him out very wrong. Atom Egoyan is drawn to stories like this, stories about the lasting injuries of childhood, and in one way or another both his “The Sweet Hereafter” and “Exotica” are about damaged girls and predatory men. “Felicia’s Journey” is based on a novel by William Trevor, and when he read it, Egoyan must have felt an instant empathy with the material.

Trevor at 71 is one of the greatest living writers, and one who approaches his characters with the belief that to understand all is to forgive all. There are no villains in his work, only deserving and undeserving victims. The story of Felicia is not uncommon: Johnny loved her and left her. If there were more about Johnny in Trevor’s story, we would know why. The glimpses we have of Johnny make him seem thoughtless and heartless, but then we see his mother and get a hint of what he is escaping from.

What we gather about Hilditch, on the other hand, is that as a child he was not mistreated, so much as smothered. Anything is toxic in large enough quantities, even love. We eventually understand his connection to the old videotapes of a French cookery program, which he watches while he prepares food, and we find out why one room of his house is filled with cooking appliances. Hilditch is a real piece of work. We see him mostly as an adult, and then in flashbacks as a child. In both manifestations he reminded me of Alfred Hitchcock, who wanted his tombstone to read: You see what can happen if you are not a good boy. Hilditch has grown into a bad boy who knows how to seem like a good one, seeking out young and helpless girls and offering them his aid. Naming some of his “lost girls” to Felicia, he says, “I was the world to them. In their time of need, they counted on me.” Some will find the ending of the film, with its door-to-door evangelist (Claire Benedict), unlikely. True, Miss Calligary is a deus ex machina, but I prefer her intervention to a more conventional thriller ending. Irony is usually more satisfying than action. And as Hilditch kneels on the wet grass next to a grave, there is pathos and at the same time that cold Hitchcockian humor.

Egoyan is such a devious director, achieving his effects at a level below the surface. He never settles for just telling a story. He shows people trapped in a matrix of their past and their needs. He embraces coincidences and weird lurches in his plots because he doesn’t want us to grow too confident that we know how things must turn out. He almost never provides a tear-jerking scene, an emotional climax, a catharsis. It’s as if his films inject materials into our subconscious, and hours later, like a slow reaction in a laboratory retort, they heat up and bubble over.

You leave “Felicia’s Journey” appreciating it. A week later, you’re astounded by it.